If I were to capture what I try to do in my work in one phrase, it would be “build trust between Japanese and European business cultures.” This of course leads to questions of how trust is defined, and therefore how it is built.

The title of my new book, Shinrai, is the Japanese word for “trust”. It is composed of two characters, shin, meaning “believe”, and rai, which means “to request”. In other words, if you trust someone, you believe they will do what you request. The character for shin can be broken down further into components which mean “person” and “word” and the character for rai can be broken down into “bundle” and “leaves or pages”. It implies communication between people is a fundamental part of building trust, but also getting things done and pulling together.

Analysing the work I have done with clients over the past fifteen years, I would say there are five components of building trust in multinational companies. In sequential order they are communication, mutual interests, processes and regulations, reliability and accountability and vision and values – and then back to communication again in a virtuous circle.

1. Communication

Having a common language is critical – this is why any initiative to help immigrants integrate into a society usually starts with language lessons. The problem for Japan is that for native speakers of European languages, Japanese is one of the most difficult languages to learn and Japanese feel similarly about English. Japanese companies can do more to help Westerners learn Japanese – an intensive course in Japan is one of the most effective ways to do this. Japanese companies can also communicate better than they do in English – it’s not enough to make English the common language or force a minimum English level on employees, management needs to communicate vision, strategy and plans in English more effectively than it currently does.

2. Mutual interests

The Economic Partnership Agreement between Japan and the EU is a classic example of common interests helping to build trust. People have differing degrees of interests, but finding mutual interests means that there is a stable basis for negotiation. Japan wants to sell more cars in Europe, European consumers are happy to have cheaper, good quality Japanese cars. Europe wants to sell more food and drink to Japan, Japanese consumers are happy to have cheaper, good quality European wine and cheese. On a micro level, this is why I always encourage Japanese expatriates in Europe to engage in small talk with their European colleagues – it’s a way of discovering mutual interests, which means mutual understanding, compromises and agreements are more easily gained.

3. Processes and regulations

Once you have discovered your mutual interests, you can come to an agreement, but it needs mutually recognised standards to work well. What are the quality and safety standards expected of a car, or a cheese in your respective countries?

When there is a low level of trust, laws, regulations and processes are needed as a fall back. However, both Japanese companies and the European Union are sometimes guilty of becoming bogged down in bureaucracy and process. You have to show you are obeying regulations and following processes in order to be trusted, but ultimately, this is not sufficient. How you do something in terms of your intentions and behaviour towards others is as important as carrying out the process correctly and obeying the law.

4. Reliability & accountability

When you trust someone, it is not only because you believe they will obey the law, but also that they will do what they say they will do. For Japanese companies, this can be hard to define, as the culture is often a family style one, where everyone’s roles are vague, with no job descriptions and rely on a seniority-based hierarchy. It’s assumed everyone will do whatever necessary, in the best interests of the family. Rules can be bent for family members but this vagueness does not work well in more diverse organisations.

The current fight between Carlos Ghosn and Nissan is focused on processes and regulations. Nissan will try to prove Ghosn flouted Japanese law, but will have to answer questions about its own internal rules. Ghosn will try to prove that he followed both internal and external regulations. But what really seems to be at stake is a loss of mutual trust between Saikawa and other Japanese executives and Ghosn. If you are an insider in a Japanese company, you are trusted as a family member to act in the best interests of the family, and rules can be bent accordingly. But once you are seen as an outsider and acting in your own interests, possibly harming the company, then the rules are applied rigidly – just as the UK is finding out as it negotiates to leave the EU.

5. Vision & Values

This is why you need a clear vision of where the company is going and how you want it to be seen. The vision and values have to be discussed with and shared with employees so they feel they belong. The values will guide them as to how they should behave in order to achieve that vision. If the vision is simply to hit various targets, within the boundaries of rigid rules and processes, without employees engaged with the company values, then the kinds of corporate scandals we have seen in both Japanese and European companies will continue, with catastrophic consequences for trust across societies and cultures.

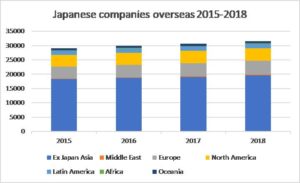

Growth in the number of Japanese companies overseas has been more muted in the past 4 years – a 7.9% increase 2015-2018. But the increase in the number of Japanese companies in Europe was above average – at 12.5%. The increases in companies in Asia (7.6%) and Latin America (5.6%) were below average – so there was a boom in Japanese investment in developing countries during the 2008-2014 period, but this died down in the past 4 years.

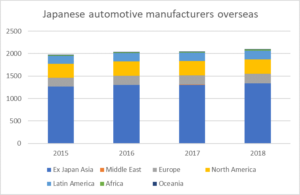

Growth in the number of Japanese companies overseas has been more muted in the past 4 years – a 7.9% increase 2015-2018. But the increase in the number of Japanese companies in Europe was above average – at 12.5%. The increases in companies in Asia (7.6%) and Latin America (5.6%) were below average – so there was a boom in Japanese investment in developing countries during the 2008-2014 period, but this died down in the past 4 years. So how about investment in automotive manufacturing – the sector that has made the most noise in Brexit UK? The number of Japanese companies overseas in the “transportation machinery manufacturing” category that Toyo Keizai uses (which presumably corresponds to automotive manufacturing) rose 6% 2015-2018, so significantly slower growth than overall. Again, Europe showed above average growth of 13%, but only represents 10% of transportation machinery manufacturers overseas operations. Over 64% of automotive manufacturer sites are in ex-Japan Asia. So although Japanese automotive companies are not pulling out of Europe – rather the reverse – the major part of Japanese automotive investment is and continues to be in Asia. So no surprises really that Honda and others are choosing to focus on Asia for electric vehicle development – that is where the largest ecosystems and supply chains are based.

So how about investment in automotive manufacturing – the sector that has made the most noise in Brexit UK? The number of Japanese companies overseas in the “transportation machinery manufacturing” category that Toyo Keizai uses (which presumably corresponds to automotive manufacturing) rose 6% 2015-2018, so significantly slower growth than overall. Again, Europe showed above average growth of 13%, but only represents 10% of transportation machinery manufacturers overseas operations. Over 64% of automotive manufacturer sites are in ex-Japan Asia. So although Japanese automotive companies are not pulling out of Europe – rather the reverse – the major part of Japanese automotive investment is and continues to be in Asia. So no surprises really that Honda and others are choosing to focus on Asia for electric vehicle development – that is where the largest ecosystems and supply chains are based.

UK is the birthplace of innovation and will not sink, despite Brexit,

UK is the birthplace of innovation and will not sink, despite Brexit,

rudlin

rudlin rudlinconsulting

rudlinconsulting “We don’t have any room to store increased stocks” says Hiroshi Seko, the UK MD of G-TEKT, a Japanese automotive supplier.

“We don’t have any room to store increased stocks” says Hiroshi Seko, the UK MD of G-TEKT, a Japanese automotive supplier.