Japanese financial services in the UK and EMEA

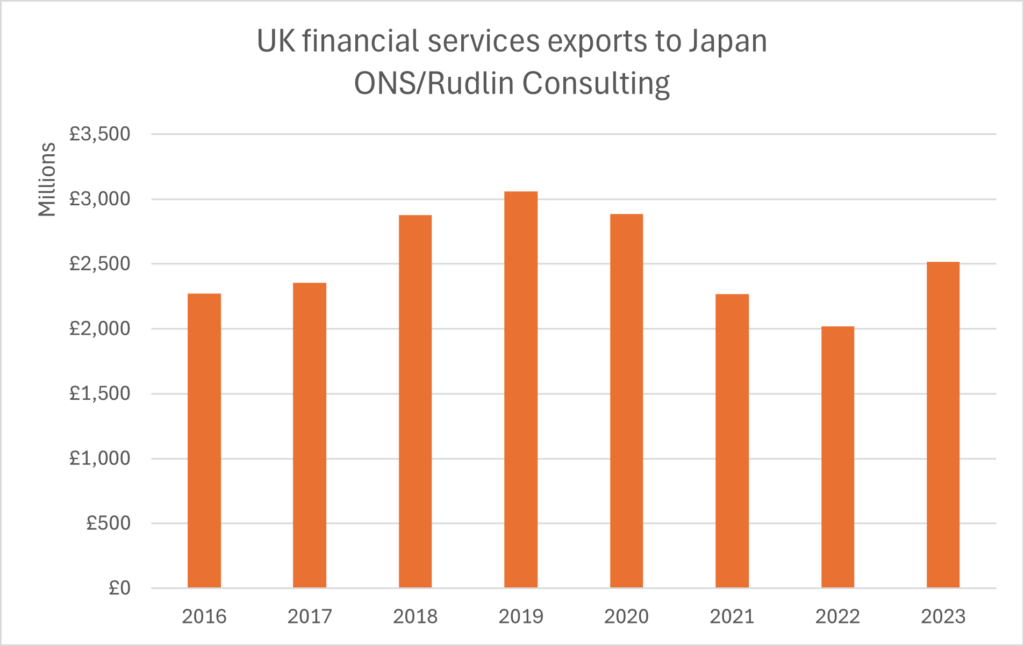

The UK’s financial regulatory authority has announced further plans to ease the rules for banks and insurers in the UK. This is in line with both previous and current British government policy of putting more emphasis on growth and investment over concerns about safety and risk.

It is also part of trying to find a benefit to Brexit, now that the UK does not need to comply with EU rules. Reducing the regulatory burden might free up resources for Japanese financial services companies to invest in innovation, or support their clients’ investment in infrastructure and zero carbon projects in the EMEA region.

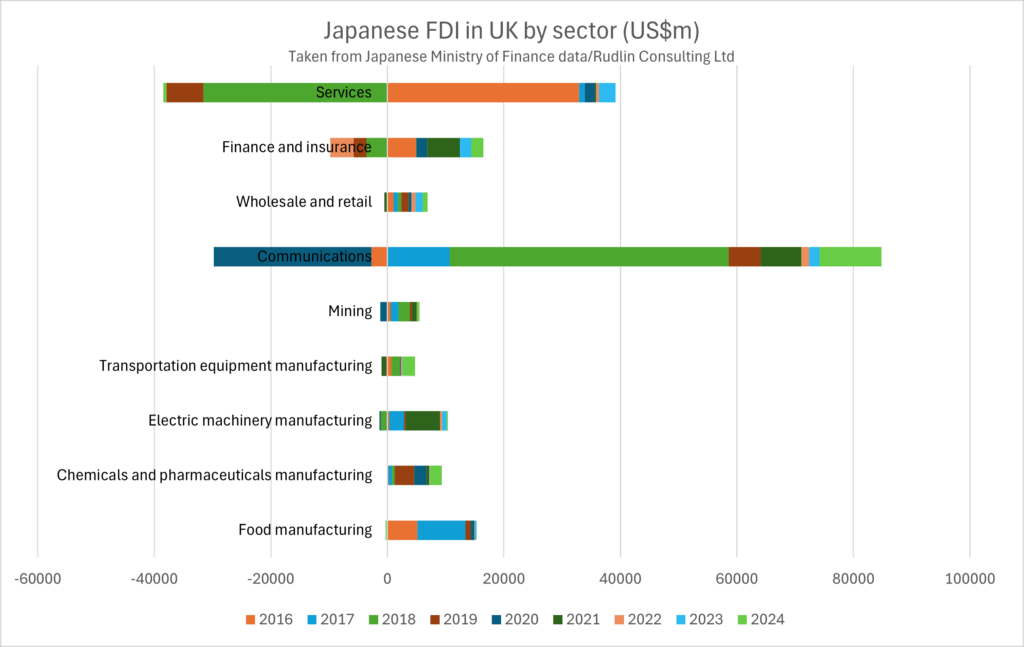

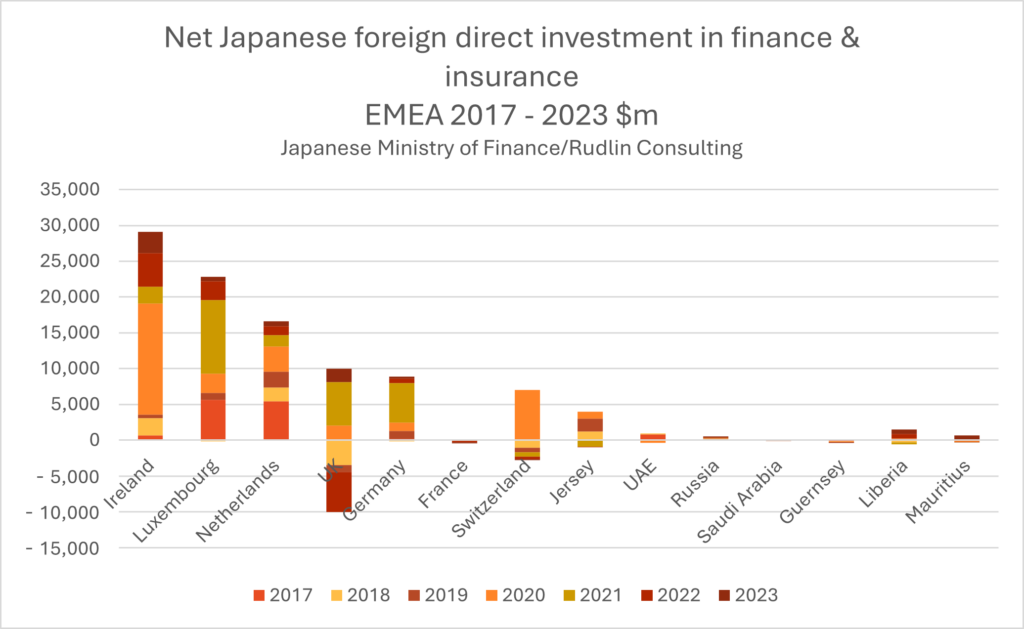

Japanese financial services capital has flowed out of the UK into Ireland, Luxembourg and the Netherlands

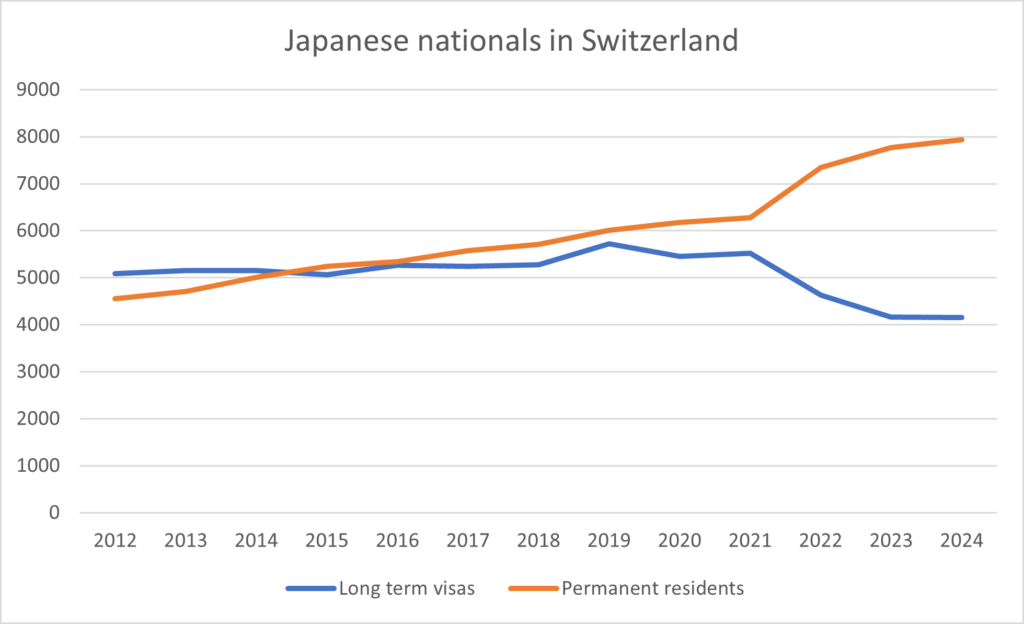

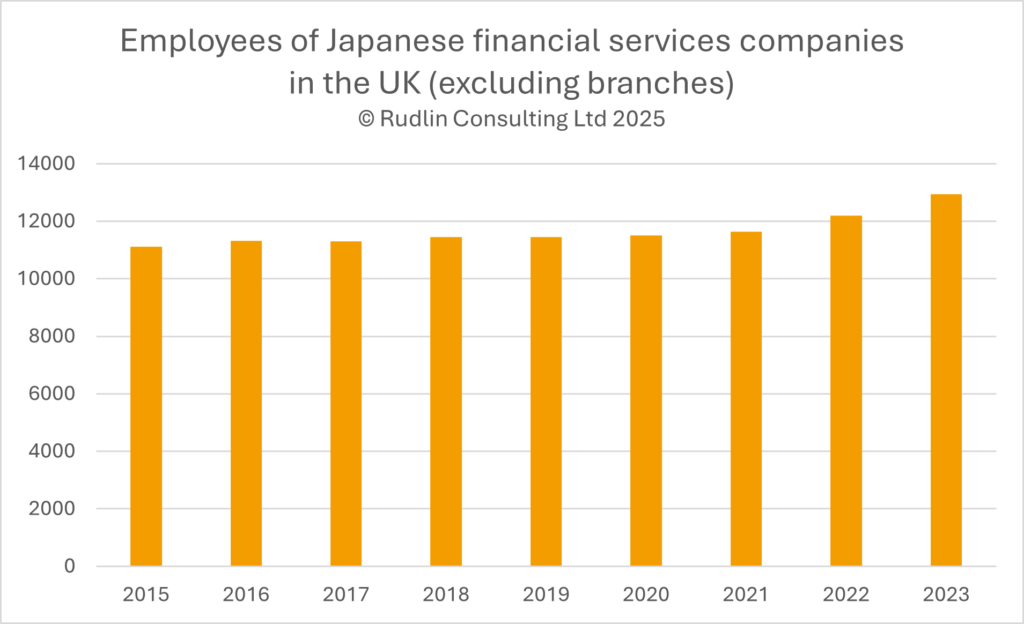

Although Japanese financial services companies have maintained the scale of their presence in the UK since Brexit in terms of employee numbers, Japanese capital has flowed out of the UK financial services sector over the past few years. There have been inflows of Japanese financial services investment into Ireland, Luxembourg and the Netherlands.* The former is undoubtedly related to the large number of Japanese aircraft leasing companies in Ireland, attracted by the beneficial taxation regime. Luxembourg is host to many Japan owned investment funds and the regional headquarters of the major Japanese insurers.

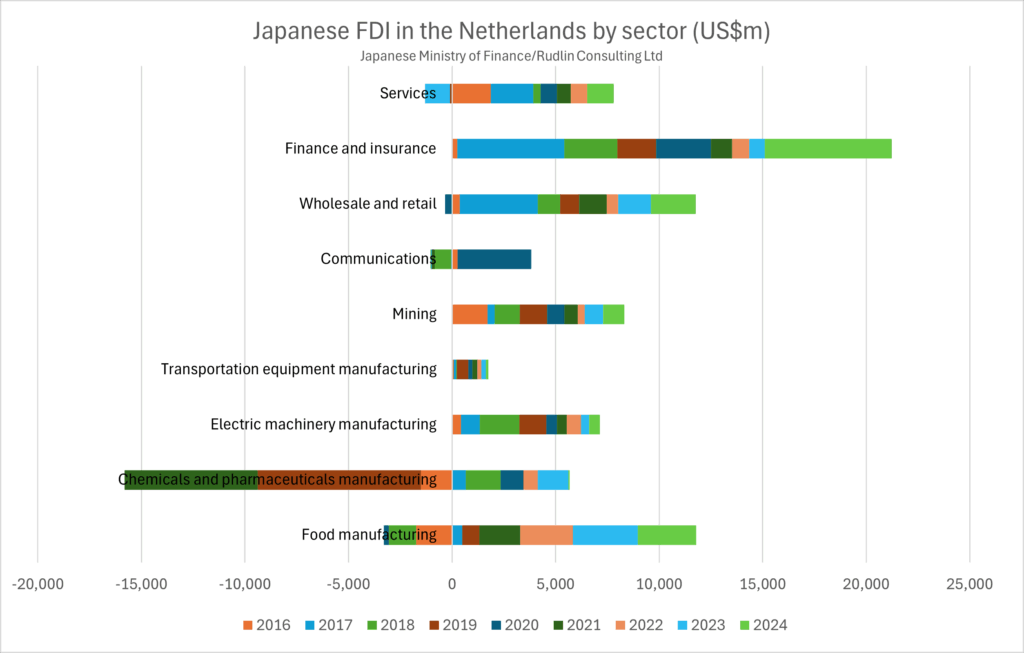

Amsterdam the post Brexit choice for EU regional HQ

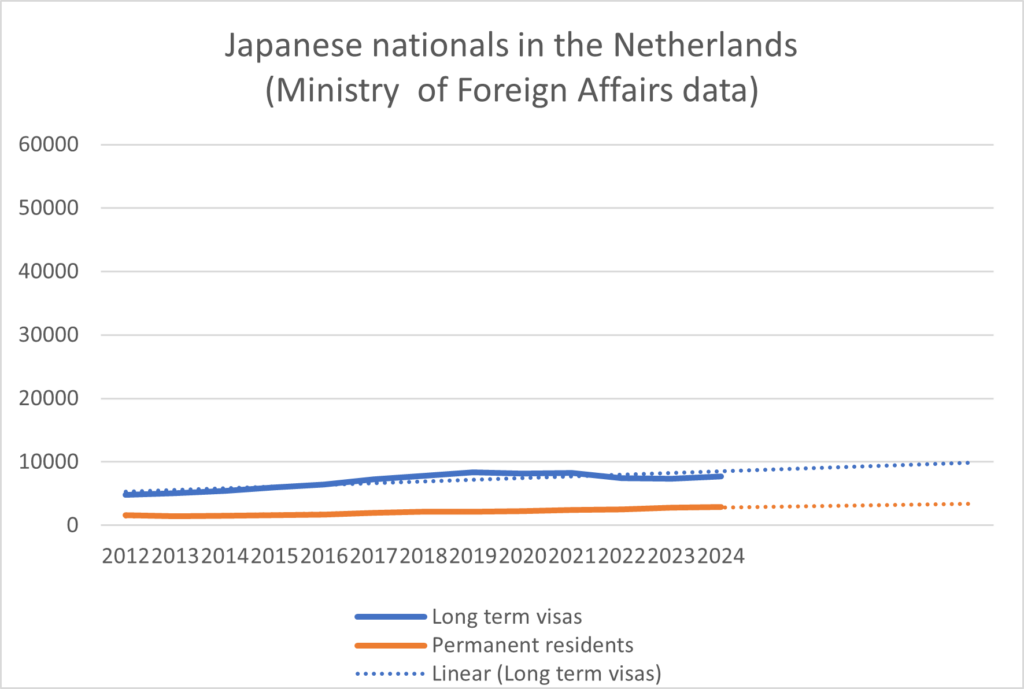

As for the flow of Japanese capital to the Netherlands, this is due to the pull of Japanese corporate customers having moved their regional headquarters there, after Brexit. As EU regulations insist that financial services firms have substantial capital and key decision makers in the European Union, many Japanese banks therefore chose Amsterdam for their EU regional headquarters too.

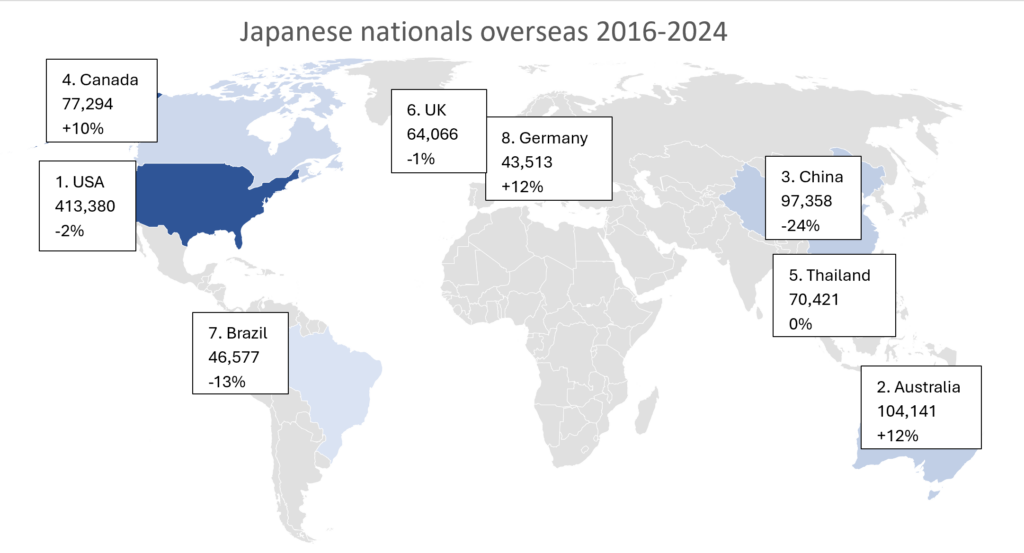

There are now around 10,000 Japanese nationals in the Netherlands – a 50% increase on a decade ago. The key decision makers at Japanese financial services firms in the region are not all Japanese however. Often the EU subsidiary reports into a UK based EMEA holding company and both the EU and UK boards of those companies have a majority of European directors.

Universal banking leading to restructuring in EMEA

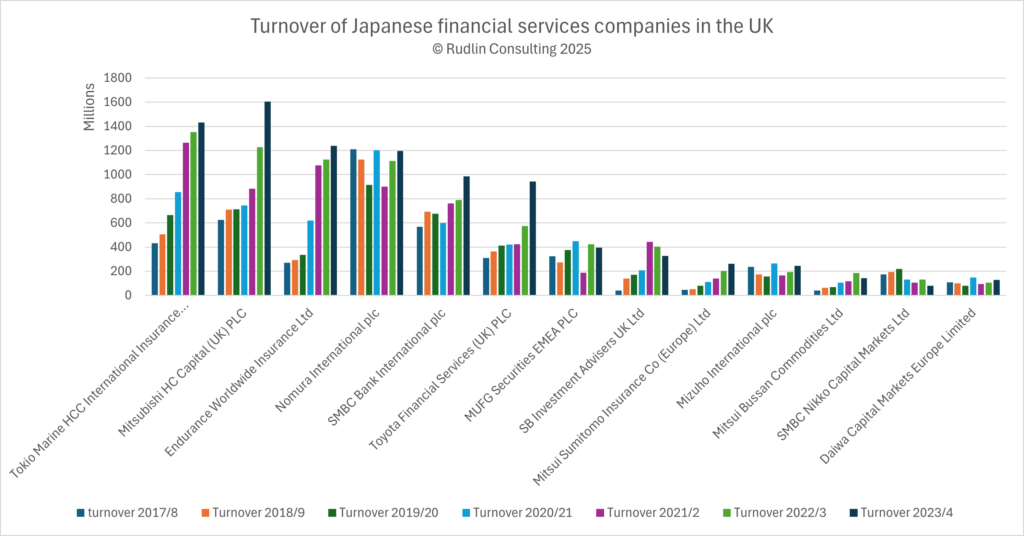

Japanese banks have undertaken substantial restructuring in the region, merging their securities business into the banking side, to become universal banks. This has also resulted in the UK becoming host to corporate function services for the whole region.

It’s clear that London continues to have an attraction as a global financial centre in terms of a large and specialist labour pool and infrastructure, as well as a place to innovate. A loosening of regulations compared to the EU’s more stringent regime will strengthen this appeal.

*data taken from https://www.mof.go.jp/english/policy/international_policy/reference/balance_of_payments/ebpfdii.htm

This article originally appeared in Japanese in the Teikoku Databank News on 12 March 2025

For more content like this, subscribe to the free Rudlin Consulting Newsletter. 最新の在欧日系企業の状況については無料の月刊Rudlin Consulting ニューズレターにご登録ください。

Read More