I’m afraid the answer to this question is yes, and no. Bits of Japanese companies are leaving. What will be left in the long run is some kind of UK-based training ground for Japanese companies’ star recruits to learn global management, with a local sales workforce attached.

I’ve come back from a recent trip to Japan clutching the brand new Toyo Keizai directory of Japanese companies overseas, which provides the data to dig into this question more deeply. It provides some clues as to whether, for example, Honda ending production in Europe is in part due to the EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement reducing tariffs to zero on cars and car parts imported from Japan. If that was the case, there might be a general shift of automotive production away from the EU.

Asia is far more important to Japan than Europe

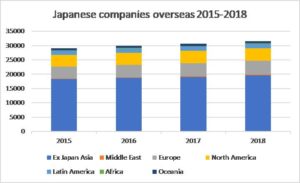

The number of Japanese companies overseas has increased 58% from 2008 to 2018, according to the Toyo Keizai data, to 31,574. The true number will be bigger, as I know from my researches into the UK, there are many Japanese companies that Toyo Keizai has not managed to track down, or who maybe just don’t respond to their surveys. 62% of Japanese companies overseas are in Asia (excluding Japan obviously), 15% in Europe, 14% in North America, 5% in Latin America, 2% in Oceania, 1% in Africa and 1% in the Middle East.

If you look at it by employee number, the proportion is roughly the same – 68% in Asia, 11% in Europe, 11.8% in North America, 6.6% in Latin America, 1.5% in Oceania, 0.7% in Africa, 0.4% in the Middle East. An obvious factor in why there are proportionately more employees to number of companies in Asia and Latin America is the greater number of manufacturing operations in those regions.

So already we see Europe represents 11-15% of the business of Japanese multinationals, and those companies are relatively less likely to be manufacturing operations than in Asia or Latin America.

The number of Japanese companies in Europe has increased 35% in ten years

Japanese companies have not been pulling out of Europe, however. There was a 35% increase in the number of companies in Europe 2008-2018, so not far off the average global increase of 37%. The biggest growth was in Latin America – 47%, then the Middle East (45%) and Africa (43%) – but from a small base. The number of companies in Asia grew 38% and only 30% in North America.

Growth in the number of Japanese companies overseas has been more muted in the past 4 years – a 7.9% increase 2015-2018. But the increase in the number of Japanese companies in Europe was above average – at 12.5%. The increases in companies in Asia (7.6%) and Latin America (5.6%) were below average – so there was a boom in Japanese investment in developing countries during the 2008-2014 period, but this died down in the past 4 years.

Growth in the number of Japanese companies overseas has been more muted in the past 4 years – a 7.9% increase 2015-2018. But the increase in the number of Japanese companies in Europe was above average – at 12.5%. The increases in companies in Asia (7.6%) and Latin America (5.6%) were below average – so there was a boom in Japanese investment in developing countries during the 2008-2014 period, but this died down in the past 4 years.

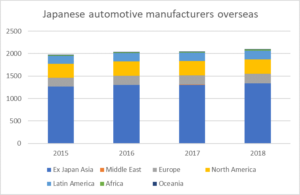

Japanese automotive manufacturers are not pulling out of Europe – quite the reverse

So how about investment in automotive manufacturing – the sector that has made the most noise in Brexit UK? The number of Japanese companies overseas in the “transportation machinery manufacturing” category that Toyo Keizai uses (which presumably corresponds to automotive manufacturing) rose 6% 2015-2018, so significantly slower growth than overall. Again, Europe showed above average growth of 13%, but only represents 10% of transportation machinery manufacturers overseas operations. Over 64% of automotive manufacturer sites are in ex-Japan Asia. So although Japanese automotive companies are not pulling out of Europe – rather the reverse – the major part of Japanese automotive investment is and continues to be in Asia. So no surprises really that Honda and others are choosing to focus on Asia for electric vehicle development – that is where the largest ecosystems and supply chains are based.

So how about investment in automotive manufacturing – the sector that has made the most noise in Brexit UK? The number of Japanese companies overseas in the “transportation machinery manufacturing” category that Toyo Keizai uses (which presumably corresponds to automotive manufacturing) rose 6% 2015-2018, so significantly slower growth than overall. Again, Europe showed above average growth of 13%, but only represents 10% of transportation machinery manufacturers overseas operations. Over 64% of automotive manufacturer sites are in ex-Japan Asia. So although Japanese automotive companies are not pulling out of Europe – rather the reverse – the major part of Japanese automotive investment is and continues to be in Asia. So no surprises really that Honda and others are choosing to focus on Asia for electric vehicle development – that is where the largest ecosystems and supply chains are based.

UK is still has the most automotive manufacturers in Europe, but is not getting any new investment

How about the UK in all of this? The UK had and continues to have the largest number of automotive related manufacturers in Europe, according to Toyo Keizai – 32 in 2015 (out of 192 in Europe) and 30 in 2018 (out of 217). I haven’t been able to identify both of the companies that have withdrawn from the UK, but one is almost certainly Keihin, 41% owned by Honda, who shut down production of vehicle engine management systems and climate control systems in the UK in 2014-5 and shifted production to the Czech Republic. The other might be more to do with renaming and consolidation rather than withdrawal of manufacturing.

Keihin’s move is clearly “pre-Brexit” but what is obvious is that the UK is not getting any new investment in the automotive sector since Brexit. Of the 29 new automotive manufacturing operations started in Europe in 2015-2018, 8 were in Germany, 4 in France, 4 in Slovakia, 3 in Spain, 3 in Italy, 3 in Hungary and 2 in the Czech Republic but none in the UK. Germany, France and the Czech Republic are now not far behind the UK in the number of automotive production sites that they host.

So the idea that the zero tariffs on cars and car part imports from Japan which would eventually arise from the EU-Japan Economic Partnership has meant that it is no longer attractive to manufacture cars and car parts in the UK or the rest of the EU also does not seem to hold – yet. In fact I was surprised to see that Western Europe has held up well against the cheaper Eastern European countries.

UK employees of Japanese companies up 20% on 2015, mainly due to acquisitions

Generally, the number of Japanese companies in the UK is still rising – 972 in 2018 according to Toyo Keizai, 11.1% up on 2015. The other countries in the top 5 – Germany, Netherlands, France and Italy are all hosting more Japanese companies too, and the numbers have grown slightly faster than in the UK, by between 11.8% to 13.5% over the past 4 years.

Many of the new Japanese in companies in the UK over the past few years have been acquisitions in biotech/pharma, high tech, outsourcing/staffing, automotive services and new arrivals have been in fintech, or investment/holding companies.

So what about the companies that have said they are leaving the UK because of Brexit, such as Panasonic and Sony? Well, rather like Keihin, they are not actually leaving the UK, just moving some functions, in this case the regional headquarters functions rather than manufacturing, to the Netherlands or Germany. This kind of “leaving” – turning what were incorporated subsidiaries into branches, has emerged in other Japanese companies too, as one reaction to Brexit. Invoicing, tax on sales, royalties etc will all be taken care of by the regional headquarters, and the UK branch will be funded by management fees.

So although the numbers employed by Japanese companies in the UK continue to rise (by 20% since 2015), this is more the result of acquisition of existing staff, rather than the creation of large numbers of new jobs that greenfield manufacturing investment brings.

During my trip to Japan last week I met with Leo Lewis, Financial Times Tokyo Correspondent, and it is to him that I owe the insight that Japanese companies will never leave the UK completely, as it is too attractive an incentive to their highflyers, to be able to promise a couple of years early in their career to learn the ropes of global business in the UK. But bits will nonetheless leave, as the recent news about Nomura’s restructuring shows.

For more content like this, subscribe to the free Rudlin Consulting Newsletter. 最新の在欧日系企業の状況については無料の月刊Rudlin Consulting ニューズレターにご登録ください。