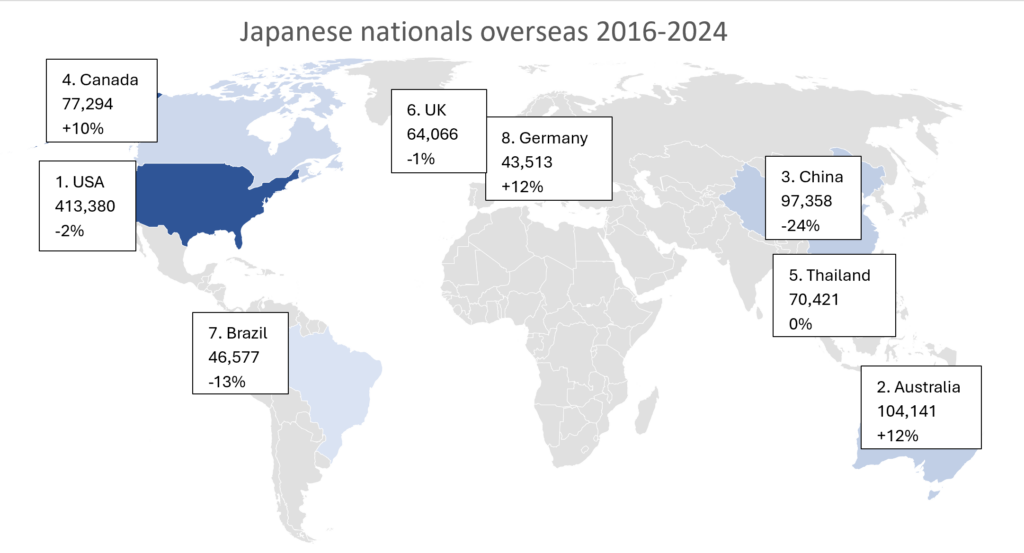

The headline in Japan on the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs latest data on Japanese nationals living overseas was that the number of Japanese living in China had dipped below 100,000 for the first time. This meant China was overtaken by Australia as the second largest host of Japanese nationals, below the USA, also for the first time.

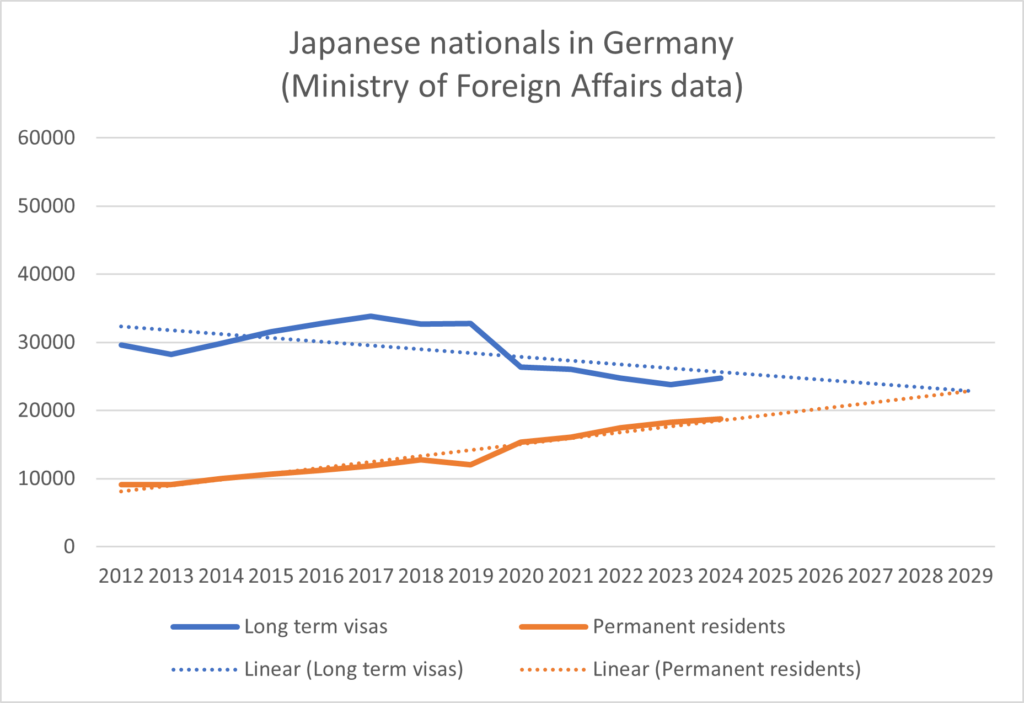

The USA is still overwhelmingly the largest host, with over 413,000 Japanese nationals living there on permanent or long term visas, but there has been a gentle decline in numbers since 2018. Similarly, the UK, which has the sixth largest number of Japanese nationals (just over 64,000) peaked in 2019 and is now around 1% down on 2016. Germany, #8, has 12% more Japanese residents than it had in 2016 – a similar growth rate to Australia, and looks to be catching up with Brazil, which has had a 13% decline in Japanese nationals.

The USA is still overwhelmingly the largest host, with over 413,000 Japanese nationals living there on permanent or long term visas, but there has been a gentle decline in numbers since 2018. Similarly, the UK, which has the sixth largest number of Japanese nationals (just over 64,000) peaked in 2019 and is now around 1% down on 2016. Germany, #8, has 12% more Japanese residents than it had in 2016 – a similar growth rate to Australia, and looks to be catching up with Brazil, which has had a 13% decline in Japanese nationals.

It may seem odd that Brazil and the USA have so many Japanese nationals considering the major migrations from Japan to those countries were at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century, but this is because in many cases, the Japanese nationals are actually third or even fourth generation. Japan does not allow dual nationality, and nationality is determined by ‘jus sanguinis’ – at least one of the parents being Japanese, rather than being born in Japan. So many children of Japanese immigrants keep their parents’ nationality despite their birthplace. This is why the Ministry of Foreign Affairs data needs to be treated with caution. The data shows those Japanese who have registered with the embassy or consulate. Clearly, if you want your children to have Japanese nationality, despite being born overseas, you would need to register them. I suspect however, that many parents both register their children as Japanese nationals, but also enable their children to take the nationality of the country they were born in, if that is legally allowed – ‘jus soli’. Others may not register with the Embassy at all, to try to stay under the radar.

There would be no way for the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs to check whether there were conflicting nationalities being claimed, until something forces the issue, such as inheritance tax to be paid in Japan, a pandemic or a change in the immigration and nationalization laws in the host country.

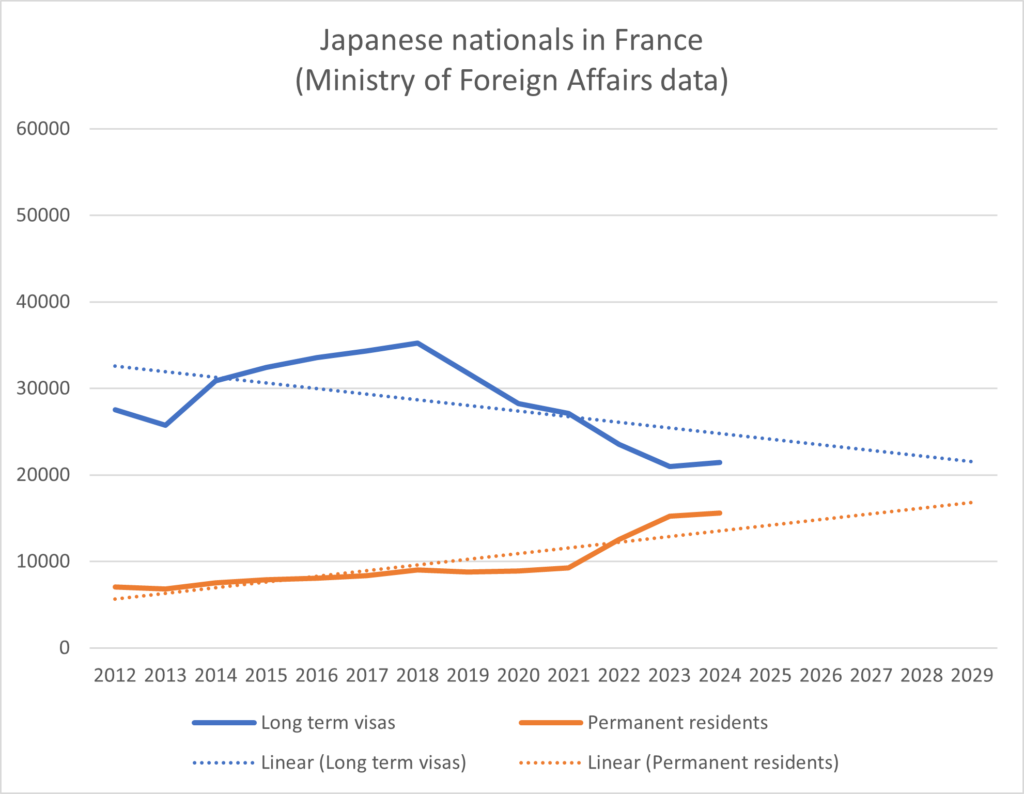

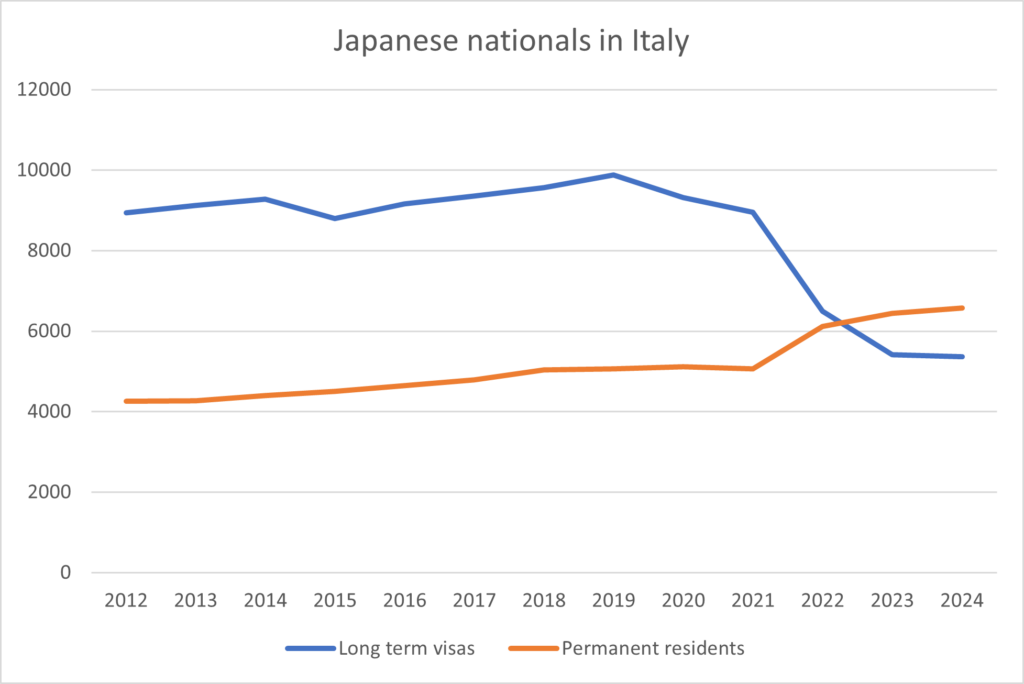

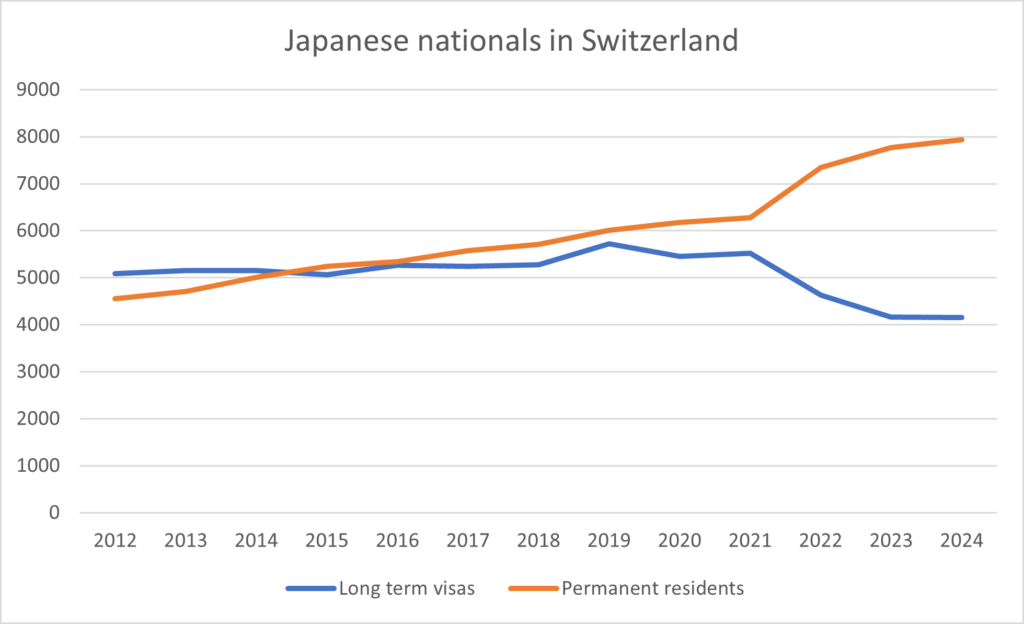

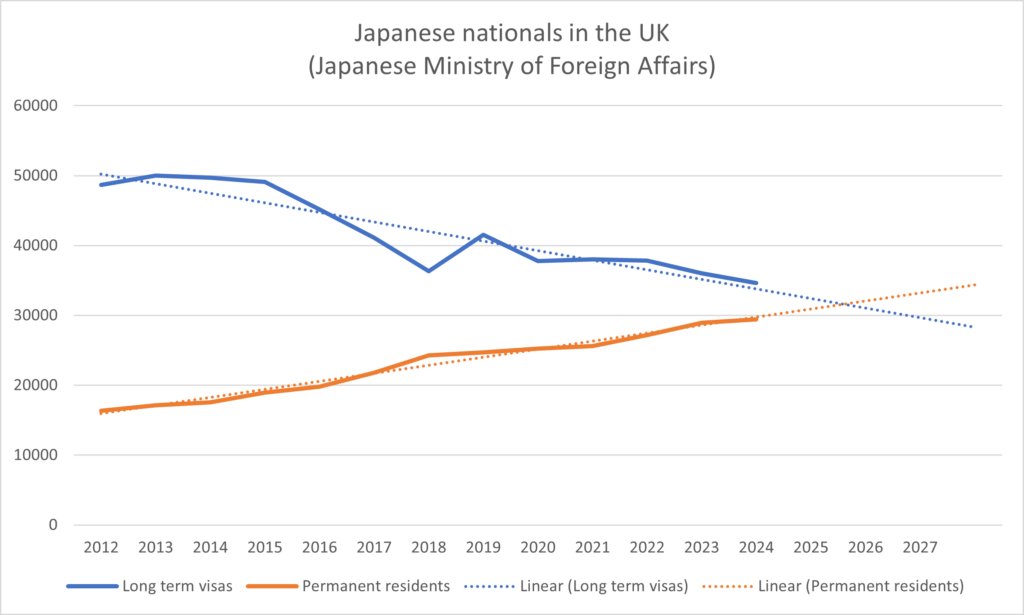

Separating out the numbers for permanent residents and those on long term visas (who are likely to be corporate expatriates) reveals the impact of legal changes, the pandemic and also long term shifts in Japanese corporate expatriation and Japanese who commit to “burying their bones” as it is said in Japanese, in a foreign country – probably due to having married and raised families in that country.

The rise of the permanent resident

If current trends continue, the number of Japanese who are permanent residents in the UK is set to overtake the number who are in the UK temporarily on working visas by around 2026 – a function of both the decline in Japanese corporate expatriates and a steady increase in the number of Japanese choosing to live permanently in the UK.

If current trends continue, the number of Japanese who are permanent residents in the UK is set to overtake the number who are in the UK temporarily on working visas by around 2026 – a function of both the decline in Japanese corporate expatriates and a steady increase in the number of Japanese choosing to live permanently in the UK.

The other major host countries (more than 10,000 Japanese nationals) where more than half the Japanese nationals are permanent residents are Argentina (96.7%), Brazil (91.7%), Canada (67.9%) Australia (61.5%), New Zealand (60%), the USA (55.7%), Italy (55.1%) and Switzerland (65.7%).

A similar crossover of Japanese permanent residents exceeding long term visa holders may occur in Germany and France within the next 5 to 10 years if the trend is projected from 2012 – but the most recent data show that there has been a slight upturn in Japanese long term visa holders in both countries and a levelling off in the number of permanent residents.

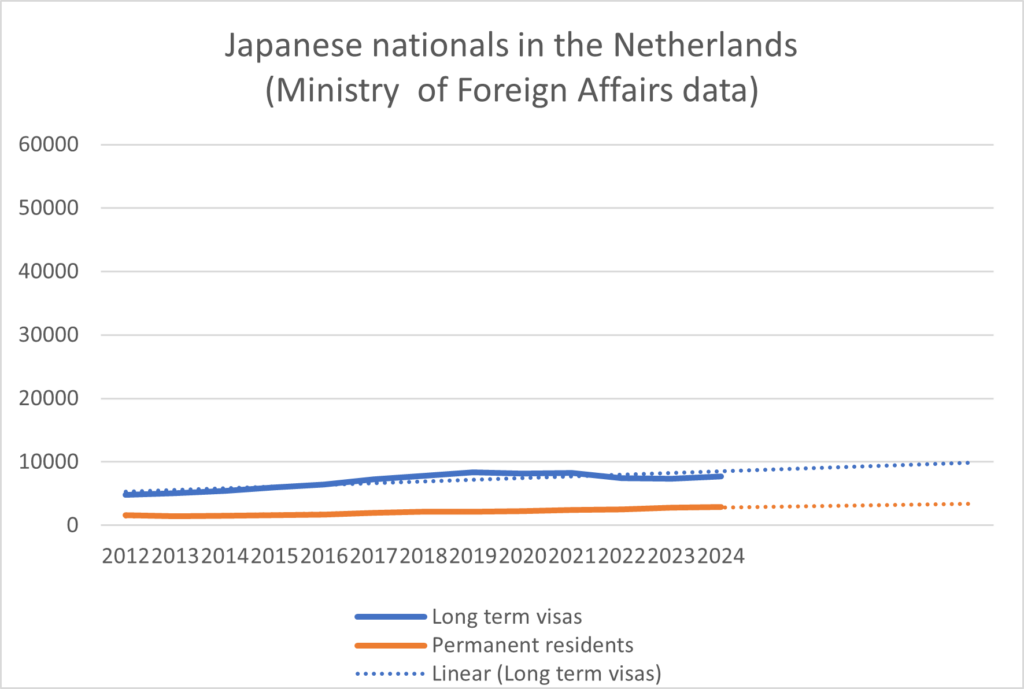

Except in the Netherlands, the Brexit benefitter

The outlier in Europe in many ways is the Netherlands. Although there only are just over 10,000 Japanese nationals living there, this represents a 53% increase on 2014. Judging by the steady rise of long term visa holding Japanese – particularly around the Brexit years, there is no sign of the gap closing between permanent and long term Japanese nationals in the Netherlands. As noted in our recent report on Japanese financial services in Europe, Japanese banks have followed their Japanese clients and reacted to Brexit by opening or reinforcing their regional headquarters in the Netherlands with assets and capital, and Japanese expatriates would seem to have followed.

Our 2025 report on Japanese Financial Services in the UK and EMEA, with a directory of 300 Japanese financial services companies in the region – can be purchased and downloaded online here

For more content like this, subscribe to the free Rudlin Consulting Newsletter. 最新の在欧日系企業の状況については無料の月刊Rudlin Consulting ニューズレターにご登録ください。