GDPR

The EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) comes into force on May 25th 2018, after which date, organizations which hold personal data on EU citizens which are not compliant with the GDPR may face heavy fines.

Many small companies like mine are struggling to comply. The regulation is clearly aimed at the larger business-to-consumer companies who hold a lot of very personal data about their customers, such as their age, sexuality, political affiliations and so on, and could use this to target them in a way that could be seen as intrusive or offensive.

I have decided, however, to make sure the personal data we hold is compliant, partly because I want my customers to feel confident that their suppliers are trustworthy, but also because I see this as a chance to improve the service we provide and slim down our customer database and mailing lists.

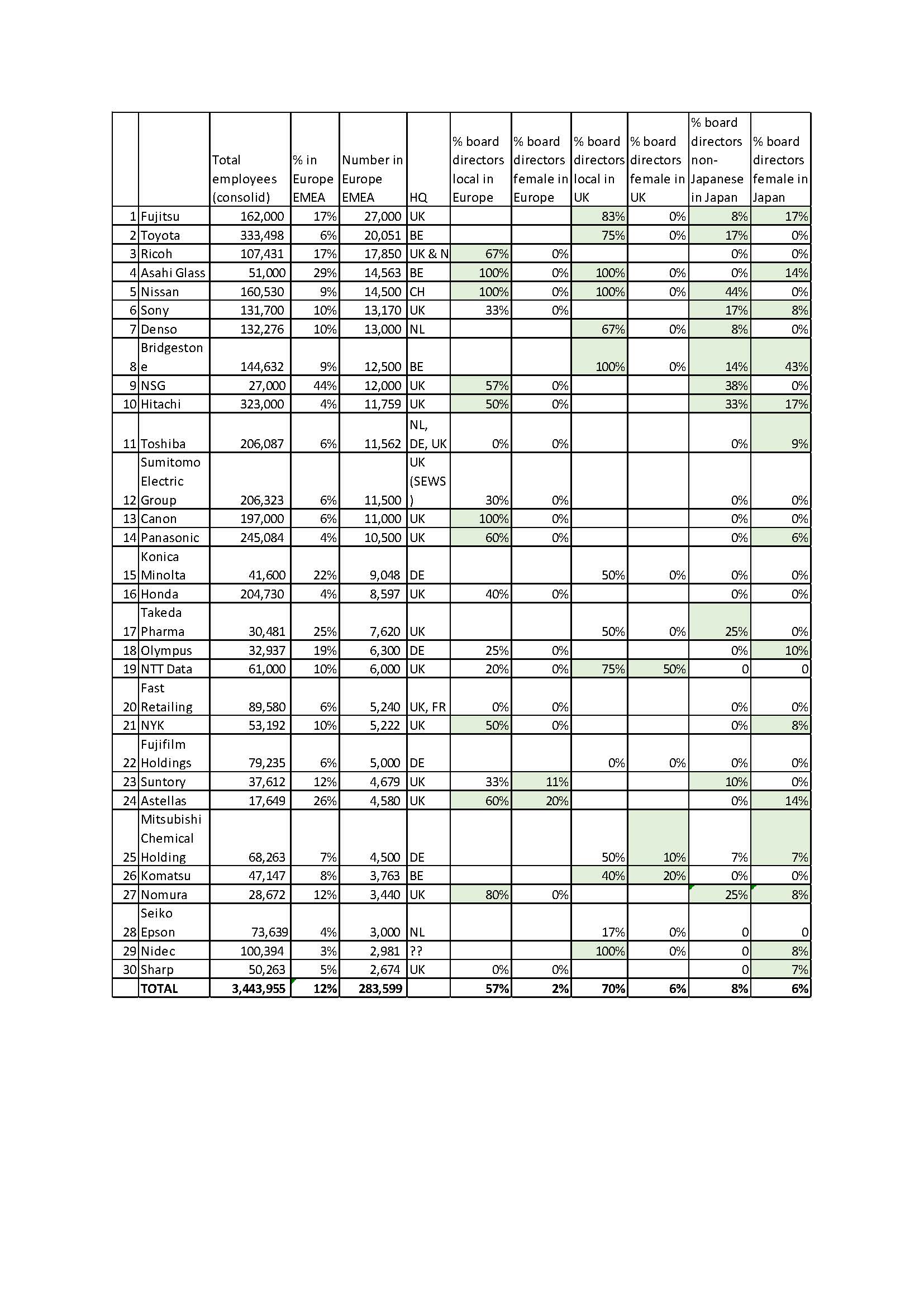

Japanese companies in Europe are undoubtedly feeling particularly nervous about the GDPR, as Honda Motor Europe was already fined by the UK’s Information Commissioner’s Office in 2017 for violating a UK regulation which has very similar requirements to the GDPR regarding consent.

Consent is the key issue with GDPR. There needs to be informed, positive consent by the customer for their data to be processed. The nature of the data (what kind of personal details) which the company will hold, and what it will be used for (emails, newsletters, postal mailing etc) have to be clearly explained. A double opt in is recommended – whereby people fill in the form, and then receive an email asking them to confirm that they do want to share their data. A clear process for them to ask to be deleted from a database also needs to be in place.

It is not possible to “grandfather” (allow old conditions to continue even if they are against the new rules) previously held personal data, so it might be safest to reconfirm with people on your database that they still consent to you processing their data. Of course, the risk with this is that many people will not consent and your mailing list will shrink.

But this brings me on to my second reason for deciding to comply as thoroughly as possible with the GDPR. I want to make sure that my newsletters are really valued by my customers. Our newsletters are not marketing our training so much as part of the after-service we provide. They help our customers refresh and add to what they learnt in the classroom.

Manufacturers are also moving away from just selling a product, to selling a solution – hardware plus surrounding services such as maintenance and support, using the Internet of Things and Big Data to provide a more customised product.

Which is of course why the GDPR has become necessary. Personal data can be used in a good way, to meet customer needs more completely, but, as we know in Europe, particularly in former dictatorships and communist regimes, personal data can be abused.

This article appears in Pernille Rudlin’s latest book “Shinrai: Japanese Corporate Integrity in a Disintegrating Europe” available as a paperback and Kindle ebook on Amazon.

For more content like this, subscribe to the free Rudlin Consulting Newsletter. 最新の在欧日系企業の状況については無料の月刊Rudlin Consulting ニューズレターにご登録ください。

Read More