Japanese financial services companies in the UK and EMEA after Brexit

Japanese financial services firms in the UK have remained fairly resilient since Brexit, in terms of turnover and headcount – with significant growth shown by the non-life insurers and leasing and financing companies, but less growth for some in the banking and securities sectors. On the other hand, the UK has had significant outflows of Japanese capital, whereas Ireland, Luxembourg and the Netherlands have had significant inflows.

Headcount

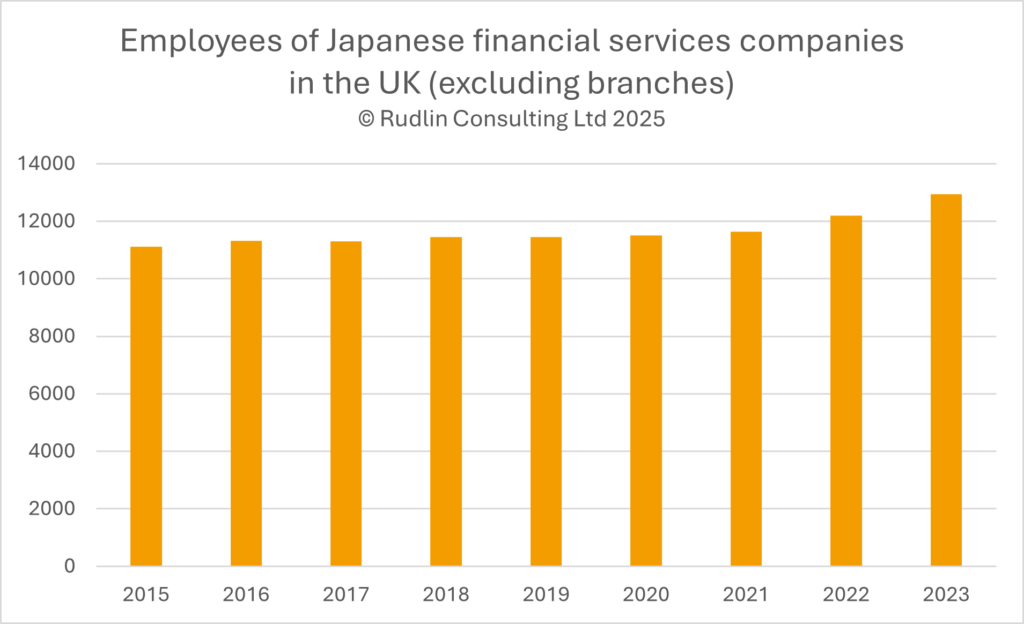

Judging by annual reports filed for the UK for the year 2023-2024, after several years of negative or little growth, Japanese financial services companies are starting to expand their hiring in the UK.

Judging by annual reports filed for the UK for the year 2023-2024, after several years of negative or little growth, Japanese financial services companies are starting to expand their hiring in the UK.

Adding in a guesstimate for the banks that are branches, there are over 15,000 employees in the Japan-owned UK financial services sector, and this total has grown by at least 10% over 2021/2 to 2023/4. This total represents around two-thirds of the total working for Japanese financial services firms in the region

This may indicate improving business for the Japanese financial services sector across the whole EMEA region, as many of the Japanese financial services firms in the UK act as EMEA regional headquarters. According to the JETRO Survey on Business Conditions for Japanese-Affiliated Companies Overseas (Global Edition) 2024, 92.4% of Japanese banks overseas were predicting a profit – higher than any other sector. The European edition of the survey showed that 60% of non-bank financial services companies were predicting an increased market share in Europe for 2024.

This overall growth conceals some varying fortunes, however. SMBC Bank International PLC has doubled in size since 2015, to 1,739 employees. Recent growth is partly due to the transfer of employees from SMBC Nikko Capital Markets with the merger of its securities business into SMBC. This merger process is expected to be completed by year ending March 2025. SMBC Nikko will continue as a derivatives business, conducted by employees within SMBC Bank International.

It is possible that the other two megabanks, MUFG and Mizuho have grown similarly, but as they are branches, it is not possible to verify this. Their securities arms – Mizuho International and MUFG Securities – grew by a third and by 18% respectively since 2015.

Other companies which have grown include Mitsubishi HC Capital, Tokio Marine, Aioi Nissay Dowa Insurance and Toyota Financial Services.

Headcount has dropped significantly 2021/2 to 2023/4 at Daiwa Capital Markets as part of their three year cost reduction programme. The 2024 report shows a £14m profit compared to an £18m loss in the previous year.

Nomura is showing a small recovery in employee numbers, but headcount at 1,876 is still nearly 25% down on 2015/6.

SBI Shinsei, formerly SoftBank owned Shinsei Bank, is making a comeback in London. It acquired British crypto currency company B2C2 in 2020 and its Japanese Chief Executive was approved by the UK’s FCA in 2024. The intention is to build up institutional business in equity, fixed income and digital and fintech investment.

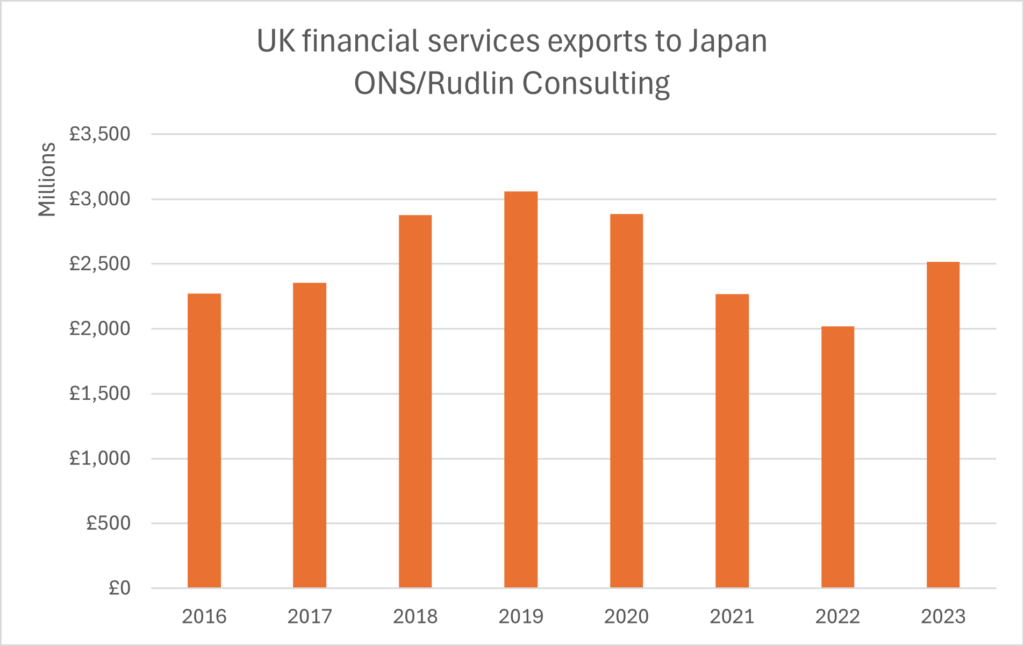

UK financial services exports to Japan

Headcount growth may be due to increased demand from Japan for UK financial servies. UK trade statistics show that financial services exports from the UK to Japan of £2.4bn represented 30% of UK services exports to Japan in the year ending Q3 2024, an increase of 2.1% (non-seasonally adjusted) on the previous year. Financial services exports to Japan grew for the first time in 4 years in 2023.

A substantial proportion of these financial services exports may be Japanese corporate purchases of the services of UK based Japanese financial services firms, or the headquarters of those firms forwarding management fees on to their operations in the UK.

Turnover

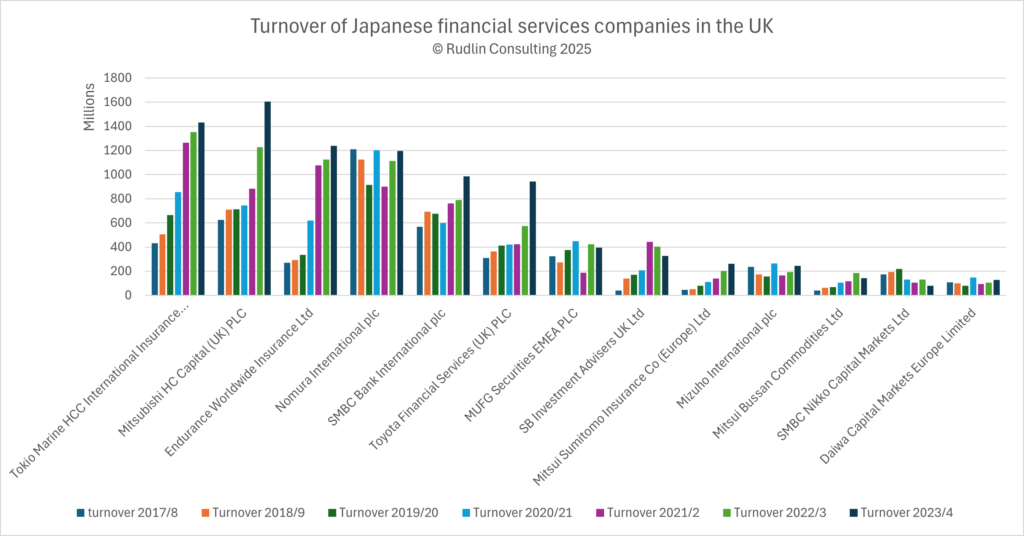

The top 14 Japanese financial services firms in terms of turnover (turnover covering everything from gross written premiums to management fees) show that securities based businesses have had a bumpy few years, but non-life insurers and leasing and financing companies have boomed, in part because of acquisitions. Tokio Marine HCC and Endurance Worldwide’s turnovers reflect their Europe-wide business holdings.

The top 14 Japanese financial services firms in terms of turnover (turnover covering everything from gross written premiums to management fees) show that securities based businesses have had a bumpy few years, but non-life insurers and leasing and financing companies have boomed, in part because of acquisitions. Tokio Marine HCC and Endurance Worldwide’s turnovers reflect their Europe-wide business holdings.

Mergers and acquisitions, entrants and exits

As far as we are aware, there were no mergers and acquisitions in the Japanese financial services sector in the UK in 2023-4. There was one closure, of retail forex broker GMO-Z.COM, which had an operation in London since 2012, and at peak employed 17 people. One newcomer to the UK was Fuyo Lease Europe, which already had established Fuyo Aviation Capital in London. It has formed a joint venture with Sumitomo Forestry to renovate office buildings in the UK.

The new wave of global acquisitions by Japanese life insurers has not brought capital directly to the UK, however Nippon Life’s acquisition of Resolution Life will mean a much larger presence in the UK, as Resolution Life services many closed book British life insurance brands.

Capital flows

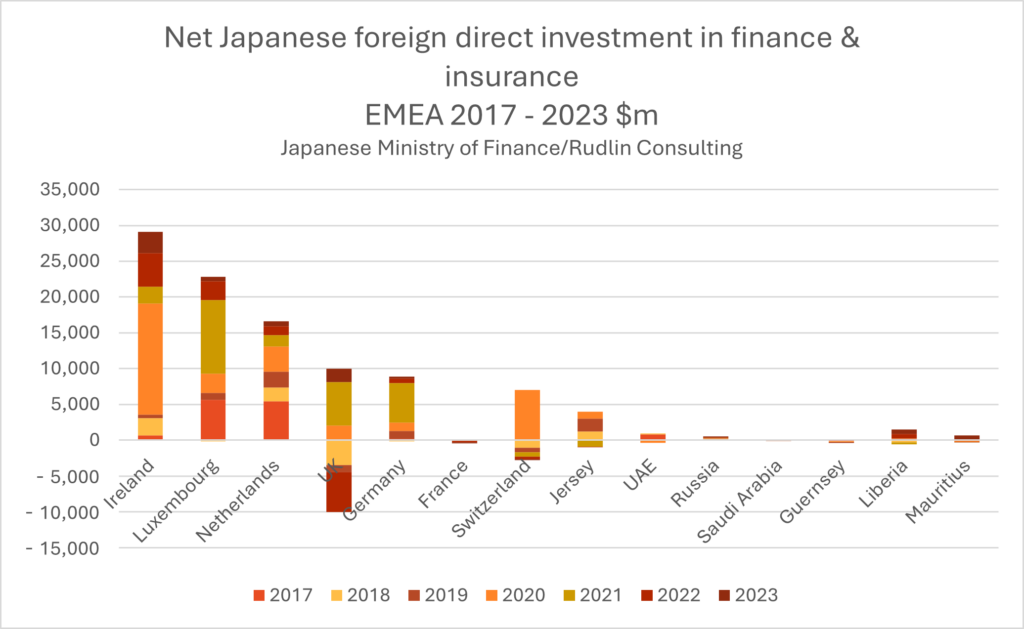

Direct investment flows from Japan, into the finance and insurance sectors, based on Japanese Ministry of Finance data,[1] show that the UK has had the largest outflow ($10bn) of Japanese investment of any country in the Europe, Middle East and Africa region from 2017 to 2023. There was a net inflow in 2023, but the balance across 2017 to 2023 is still slightly negative.  (converted from JPY to USD by rate for each year)

(converted from JPY to USD by rate for each year)

Capital has flowed into Ireland, Luxembourg and the Netherlands since 2017 – this may be partly for favourable taxation reasons, as a reaction to the Brexit referendum but also as funds for specific financial services – for example, in Ireland’s case, for aircraft leasing. Germany and Switzerland have also seen positive flows, but France has seen a small net outflow.

Luxembourg hosts the EU headquarters for insurance companies such as Sompo and Endurance as well as various fund management companies.

Japanese banks have made some investments in British companies in 2023-24, for example Mizuho Bank invested $20 million in U.K. climate change investment and advisory firm operator Pollination Global Holdings. It is aiming to use the Pollination’s know-how to boost domestic and overseas advisory services in environmental areas and information disclosure and also to set up carbon credit projects.

Assets

Japanese banks are still small compared to other banks in Europe, in terms of total assets. The top ten biggest banks in Europe all have assets of over €1trn, whereas the biggest Japanese megabank in Europe is SMBC International, in the UK, with €51bn in assets (down from €53bn the previous year). SMBC EU AG in Germany is the second largest with €23.1bn (a 30% increase on the previous year). MUFG Bank EU has €12bn in assets and Mizuho Bank EU has €5.2bn (a 14.8% increase on the previous year).

Nomura International in the UK has total assets of €216.5bn – around the same as the assets of other Japanese financial firms in Europe combined. Nomura Financial Products GmbH has assets of €18bn, up from €14bn the previous year. They state in their most recent report that they expect assets to remain within the €15 to €20bn range over the next 24 months.

As can be seen from the chart below, total assets held in the UK have declined over the year, and mainly increased in the EU.

| 2023/4 | 2022/3 | |

| Nomura International (UK) | €216.5bn (-9%) | €238.1bn |

| MUFG Securities EMEA (UK) | €74.7bn (-12%) | €85.1bn |

| SMBC International (UK) | €48.6bn (-5%) | €51.1bn |

| Mizuho International (UK) | €29.5 bn (-9%) | €32.5bn |

| SMBC EU AG (Germany) | €23.1bn (+30%) | €17.7bn |

| Nomura Financial Products GmbH (Germany) | €18.1bn (+23%) | €14.7bn |

| MUFG Bank (Europe) (Netherlands) | €12.1bn (-5%) | €12.8bn |

| Mizuho Bank Europe (Netherlands) | €5.2bn (+13%) | €4.6bn |

| MUFG Securities Europe | €4.2bn (+5%) | €4.0bn |

| Norinchukin Bank Europe (Netherlands) | €3.1bn (+24%) | €2.5bn |

(GBP£1 to €1.19 US$1 to €0.97)

Daiwa Capital Markets Europe restructured its balance sheet and business model in 2023 is not included here

Localisation

There has been regulatory pressure on Japanese financial services companies in the UK to improve their corporate governance and risk management since the Lehman Shock of 2008. This has resulted in a reduction of executives being sent from Japan and more locally experienced executives being appointed as executive directors. The branches have not been under as much pressure to localise, and their senior executives are therefore largely Japanese headquarter expatriates. Most of the larger Japanese financial services firms in the UK have more than 30 Japanese expatriate employees. Many of these are at the trainee level, however.[2]

| UK entities | Total board members | % non-Japanese |

| SMBC Bank International | 10 | 70% |

| Mizuho International | 9 | 60% |

| MUFG Securities EMEA | 9 | 70% |

| Daiwa Capital Markets Europe | 6 | 67% |

| Nomura International | 8 | 75% |

SMBC Bank International has ten board members, of whom three are Japanese directors from Japan HQ including the CEO (who has been on the board since 2018 and was appointed CEO in 2023). Alan Keir, formerly of HSBC, was chair of the board for eight years, stepping down in September 2024. He has been replaced by Sophie O’Connor. Of the 1,739 employees in London, 161 are Japanese expatriates.

The Managing Executive Officer, Head of EMEA, Deputy Head of EMEA and Head of Japanese Banking Europe at Mizuho Bank London branch are Japanese nationals from Japan headquarters. Mizuho International PLC has nine board members, of whom four are Japanese directors from Japan HQ, including the Deputy President Yoji Imafuku, appointed in 2024. The CEO Suneel Bakshi has been in post since 2019.

MUFG Bank’s Regional CEO for EMEA and the Managing Director are both Japanese nationals from Japan headquarters. MUFG Securities EMEA PLC has nine board members, three of whom are Japanese directors from Japan HQ. The CEO is Chris Kyle and the Regional Chief Executive Officer is Hidefumi Yamamura, appointed in 2024. 46 of the 291 employees at Mitsubishi UFJ Trust and Banking are Japanese expatriates.

Maria Bentley took over as chair of the board of Daiwa Capital Markets in 2024 and slimmed the board membership to six, with four people leaving in 2023/4, including two Japanese directors from Japan headquarters. There are now two Japanese board members (both from Japan HQ – the President and a female executive director) and four non-Japanese directors, including Megan McDonald, who became CEO in 2022.

Jonathan Lewis, who had been CEO of Nomura International and Nomura Europe Holdings for ten years, has stepped down, and has become Chair for Nomura Financial Products Europe, Instinet Europe and Nomura Reinsurance (Guernsey). He has been replaced by John Tierney, who has been with Nomura for 26 years. There are now eight board members, two of whom are Japanese directors from Japan HQ, including the Vice-Chairman.

European structure

The European Central Bank and local regulators have demanded that critical decision-making and risk management take place within the EU, post Brexit. Japanese firms have responded by placing executives and substantive operations within the EU. As noted in the previous section, this has not led to any significant shrinking of presence in London and the number of employees in Japanese financial firms in the UK still far outnumber those in the European Union.

It would also seem from the disclosures and annual reports that the European Union banking firms now have to make that the past few years have been quite costly in terms of bolstering presence in the EU, and some restructuring and branch closures have taken place across the EMEA region.

All three banks are bringing their European securities operations under the wing of their European banks, to create universal banks.

The London operations of Japanese financial firms have repositioned themselves as the (non-EU) Europe, Middle East and Africa headquarters, making use of London’s financial infrastructure, expertise, and established market networks.

| Total board members | % non-Japanese | |

| MUFG Bank (Europe) NV | 4 | 75% |

| MUFG Securities Europe NV | 6 | 83% |

| Mizuho Bank Europe | 3 | 33% |

| Mizuho Securities Europe | 3 | 100% |

| SMBC Bank EU executive board | 6 | 67% |

| SMBC Bank EU supervisory board | 4 | 50% |

| Norinchukin Bank management board | 4 | 25% |

| Norinchukin Bank supervisory board | 4 | 50% |

| Nomura Financial Products Europe | 6 | 67% |

MUFG opened MUFG Bank (Europe) NV in the Netherlands in 2016, before the Brexit referendum. The expansion since then of the functions of the regional headquarters led to increased costs, followed by a three-year plan to increase revenue, reduce costs and maintain strict internal controls and governance, resulting in the closure of branches in Barcelona, Warsaw and Prague.

The Bank’s remaining branches are in Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy and Spain (Madrid). It employs 800 people in the Amsterdam HQ and 200 in Germany. There are four members of the management board, three of whom are European including the CEO. The Japanese expatriate director is deputy President. The Chair is also European.

MUFG operates other financial services such as leasing and fund services in Ireland and Luxembourg. MUFG Securities Europe NV, a subsidiary of MUFG Securities EMEA was established in 2018, also in Amsterdam, and has 58 employees. It has a two tier board of six people, one of whom is a Japanese expatriate, who is the CEO, appointed in 2022.

From July 2025, MUFG Securities’ global subsidiaries will be managed by MUFG Bank instead of MUFG Securities Holdings.

Mizuho Bank Europe was established in the Netherlands in 1974. It has branches in Brussels, Vienna and Madrid, employing 121 people in total. There are three members on the management board, two of whom are Japanese expatriates – the CEO and the Chief Business Officer. The other operations in Europe are branches of Mizuho Bank Japan – Frankfurt, Duesseldorf, Milan and Paris.

Mizuho Securities Europe was established in 2020 in Frankfurt, with branches in Madrid and Paris, and employs 43 people. All three members of the board are German. Work is underway to merge the EU securities business into Mizuho Bank Europe to create a universal bank, focused on Amsterdam, Frankfurt, Paris and Madrid. This will, subject to regulatory approval, mean the closure of Mizuho’s Brussels, Düsseldorf, Milan and Vienna operations.

In the UK, Mizuho Corporate Services EMEA was formed in 2023 to provide corporate function services to the region. It started operations on April 1 2024 and 900 employees were transferred to it from Mizuho International PLC and Mizuho Bank London branch.

SMBC Bank EU opened in Frankfurt in 2019 and now has 328 employees. It has branches in Amsterdam, Prague, Madrid, Dublin, Milan, Paris and Düsseldorf employing a further 104 people. SMBC Nikko Bank Luxembourg has now been brought under SMBC Bank EU’s umbrella, as part of the move to a universal bank. There are 6 members of the executive board of SMBC Bank EU, two of whom are Japanese expatriates, including the chair. The CEO is Stanislas Roger. There are four members of the supervisory board, two of whom are Japanese expatriates.

The Norinchukin Bank opened a subsidiary in the Netherlands in 2018 and now employs around 68 people. The supervisory board has four members, two of whom are Japanese expatriates, one of whom is the Chair of the board. There are also four members of the management board, three of whom are Japanese expatriates, including the Chair.

Nomura set up Nomura Financial Products Europe GmbH in 2017, which has branches in Italy, Spain, France, Sweden, Netherlands, Switzerland and Finland. It has six members on the management board, 2 of whom are Japanese expatriates – one of whom is the CEO, appointed in 2024. Other Nomura subsidiaries include Nomura Funds Ireland PLC.

Daiwa Capital Markets has operations in Frankfurt (Daiwa Capital Markets Deutschland GmbH established in 2017, CEO Fujino Yusuke, appointed 2023) and a representative office in Paris.

Mitsui Sumitomo Insurance has announced in June 2024 that it will merge its MS Amlin organisation (primarily based in the UK) with MSIG Insurance Europe, headquartered in Cologne, Germany. The group management services company, MSIG Corporate Services (Europe), is based in the UK. MS Amlin Insurance SE is currently headquartered in Belgium with branches in Amstelveen, Paris and London.

Klaus M. Przybyla will be the CEO of the new company. MSIG Insurance Europe currently has four management board members, one of whom is Japanese.

MSI rebranded MS Amlin AG in Switzerland as MS Reinsurance.

Tokio Marine Europe SA is based in Luxembourg, and is a subsidiary of HCC International Insurance Company Plc in the UK. It has over 350 staff in offices across Europe.

CIS, Middle East and Africa

The search for growth has taken Japanese companies and financial services firms to higher risk markets in the CIS and EMEA, but as yet, their presence is small and there have been some closures of branches.

Thanks to Saudi Arabia’s new Regional Headquarters programme, providing all kinds of carrots and sticks for foreign multinationals to set up their Middle East regional headquarters there, we may see more Japanese activity there.

Mizuho is the only Japanese bank so far to respond to the programme, setting up a separate Middle East and Africa regional headquarters in Riyadh, in November 2024. According to Mizuho it expects further need for financing, including investment in infrastructure in the region, to move towards a net zero society and reduce oil dependence.

It has also partnered with Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund to create a Tokyo-listed exchange-traded fund featuring Saudi shares.

SMFG has also recently signed a Memorandum of Understanding with the National Infrastructure Fund of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia to support infrastructure development projects in Saudi Arabia.

All of the Japanese financial services firms continue to have operations in Russia.

Back office and corporate services

Mizuho set up Mizuho Global Services India in 2020 and intends to triple its tech and administrative staff in India to around 1,000 workers by the end of fiscal 2027, turning the country into its main hub for these operations. Nomura has had a regional services office in India for the past twenty years.

The UK continues to have strength in providing corporate services such as learning & development, marketing, logistics, law and finance and accounting, reflected in the recent establishment of Mizuho Corporate Services EMEA in the UK.

Human Resources

Nearly half of new hires in Japan at the Japanese megabanks in 2024/5 will be midcareer workers, as lenders seek specialized talent, rather than hiring new graduates who are then trained as generalists as before. Japanese banks in Europe are also hiring from the growing pool of local Japanese people, who have permanent residency in the UK.

London will continue to have a role in training up a new generation of specialists. SMFG is recruiting graduates in Japan for a fast track to work overseas in New York or London from as early as their second year. Mizuho and MUFG have similar schemes.

As part of their drive to counter the labour shortages in Japan and recruit specialists, Japan’s banks have continued to build up and celebrate their alumni networks.

2024’s headaches

- MUFG Bank Japan employees stealing customer assets from safe deposit boxes

- Nomura was fined for manipulating Japanese government bond futures market

- A former Nomura employee was charged robbery, attempted murder and arson of a customer

- Sompo Insurance CEO stepped down to take responsibility for the company’s involvement in used car dealer Bigmotor Co.’s insurance fraud scandal

- Japan’s FSA penalized MUFG units for unauthorized sharing of client data

- Cyberattacks (DDoS) hit both MUFG and Mizuho in Japan

Conclusions

- Past history and recent trends in Japanese financial services companies in the UK reflect the continuity of London’s attraction as a global financial centre in terms of a large and specialist labour pool and infrastructure.

- Despite Brexit, the number of people working for Japanese financial services companies in the UK has remained steady, with some recent growth.

- Turnover in the UK continues to grow – in part driven by global acquisitions rather than acquisitions of British companies, as happened in the past.

- The great majority of employees in Japanese financial services companies across Europe, Middle East and Africa are in the UK. The UK is often host to management and corporate function services for the whole region, although often administrative and IT functions are further outsourced to India.

- In order to comply with EU regulatory pressures, Japanese financial services have all set up subsidiaries within the European Union, and placed both locally experienced and Japanese expatriate executives on the boards of these subsidiaries. Often these subsidiaries still report into a UK holding company, and the more senior regional executives are still based in the UK.

- The picture is not so positive for the UK for the securities businesses however, or capital flows. There is a discernible shift of capital to Amsterdam for banking and securities and also to Luxembourg for fund management and Ireland for aircraft leasing.

- Japanese financial services firms are also looking to invest or support their clients’ investment in infrastructure, green energy and zero carbon projects, in the UK, EU and Middle East

- Turnover in securities and investment banking firms has not shown consistent growth and there has been some restructuring, consolidating and closing of smaller operations in the region.

- When Japanese financial services companies have globalised through acquiring a major multinational (such as Tokyo Marine acquiring HCC, Sompo acquiring Endurance, Nomura acquiring Lehman Brothers), then they continue to have global clients and behave accordingly in terms of governance and where they deploy resources.

- Japanese financial services companies, mainly banking and non-life insurance, that are still servicing a large number of Japanese corporate clients may also be looking to the European Union more, if those Japanese corporate clients have their main financial and legal bases there – as companies such as Panasonic and Sony now do. We expect further capital to flow to the EU accordingly. Another indicator of this shift is the 50% increase in the number of Japanese nationals in the Netherlands over the past ten years, although at around 10,000, this is still one-sixth of the number of Japanese people the UK hosts.

[1] Note, however, that data is often not disclosed in full in Japanese Ministry of Finance FDI reports, for confidentiality reasons.

[2] According to the Japanese Chamber of Commerce and Industry in the UK 2024 directory

This is an excerpt from our 2025 report on Japanese Financial Services in the UK and EMEA, with a directory of 300 Japanese financial services companies in the region – which can be purchased and downloaded online here

For more content like this, subscribe to the free Rudlin Consulting Newsletter. 最新の在欧日系企業の状況については無料の月刊Rudlin Consulting ニューズレターにご登録ください。

Read More