This post is also available in:

Executive summary

In the seven years since the Brexit referendum, the benefits of Japanese long term planning for resilience have become clear. Although employment by Japanese companies in the UK has fallen since 2018/9, this is largely in the automotive sector, triggered by the closure of the Honda Swindon plant. Non-automotive manufacturing employment and investment have stayed steady, but there have been no new manufacturing companies coming to the UK.

Employment in the wholesale sector has also fallen, as Japanese companies move their European logistics, warehousing and coordination functions to the EU. There has been significant disinvestment from the UK financial sector, but again employment seems to have held steady.

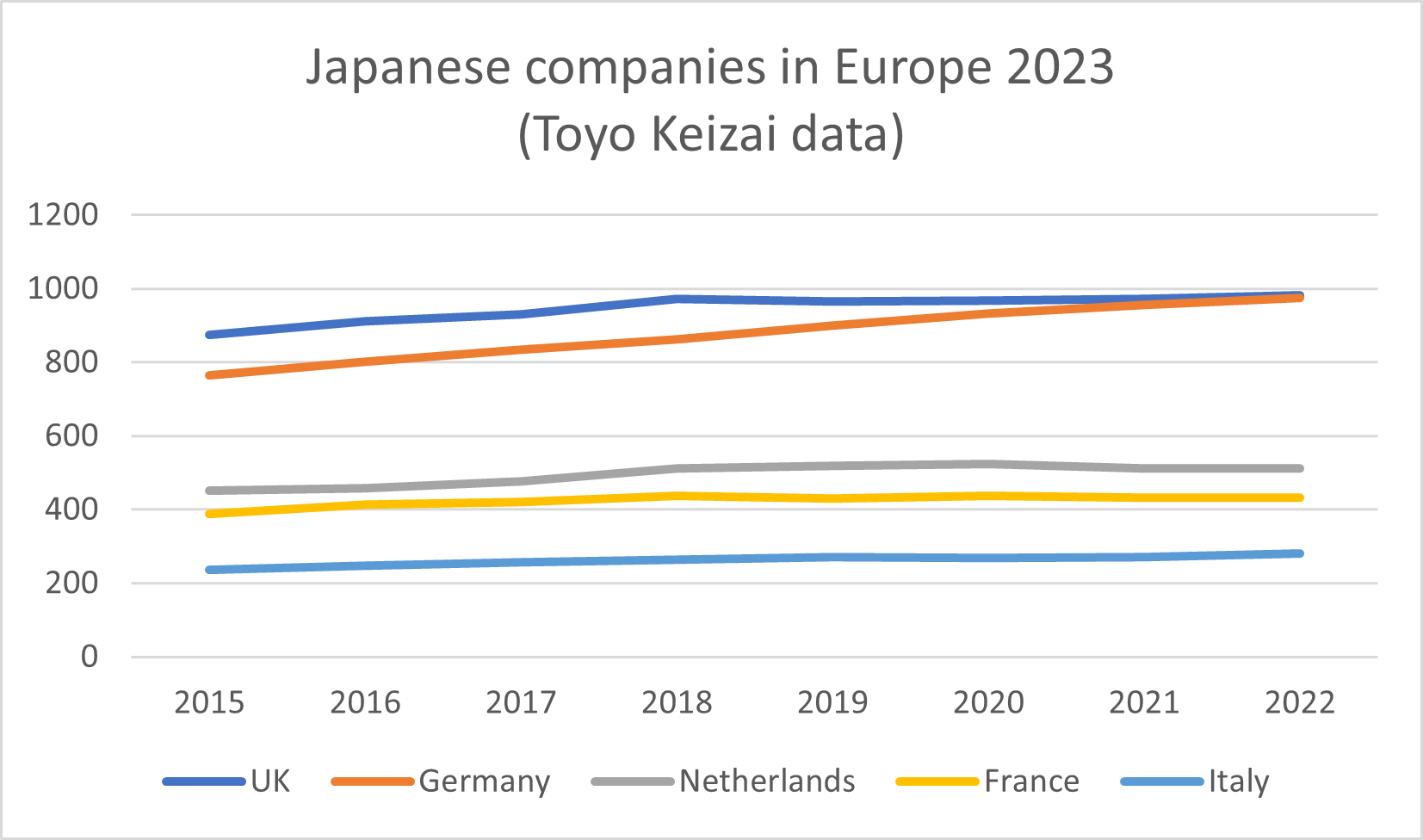

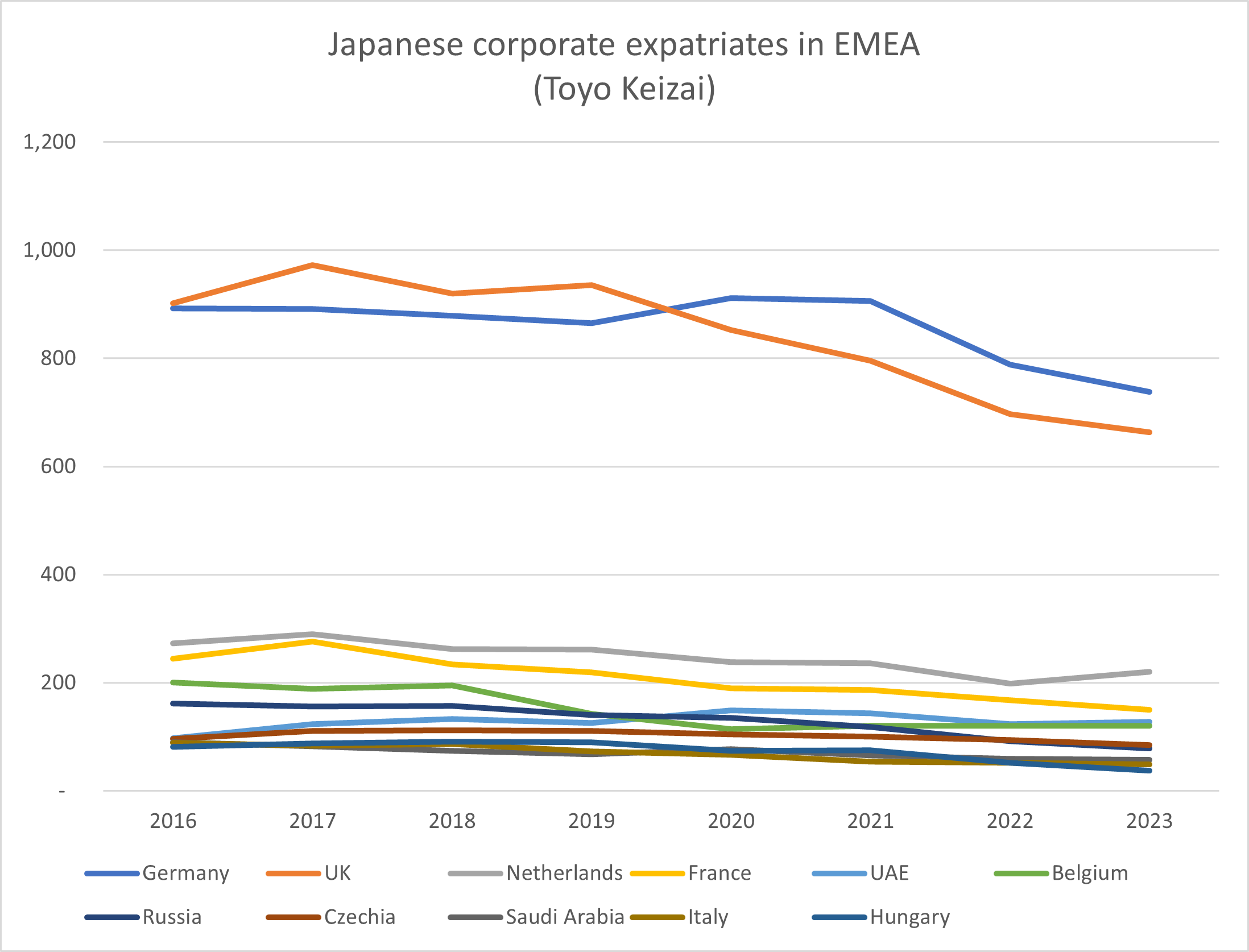

Germany has almost caught up with the UK as the largest host of Japanese companies in the EU and has overtaken the UK as the largest host of Japanese corporate expatriates.

Now the smoke and fog of Britain’s departure from the EU, and the pandemic have cleared, a new third phase of Japanese investment is taking shape. It is more focused on geopolitical concerns around climate change, energy, defence and security. The UK is seen as an important partner in this, but needs to ensure that it strengthens its long term policy commitments to these sectors, which require large investments and the support of host communities, as well as collaboration and synchronization with the EU, Africa and the Middle East.

Contents

Employment by Japanese companies in the UK grew to 2018/9, then shrank since

Germany has nearly caught up with the UK as a host of Japanese companies

More company closures in the UK than in Germany

A similar number of new Japanese companies opened in the UK and Germany since

UK still the target of Japanese M&A, but on a smaller scale than before

Switzerland overtakes the UK as largest net recipient of Japanese investment in Europe

Manufacturing employment holding steady, apart from the automotive sector

Net disinvestment in UK financial services sector, although employment remains steady

Germany has overtaken the UK become the largest host to Japanese corporate expatriates in Europe

What does it all mean? An acceleration of trends, new and old

Employment by Japanese companies in the UK grew to 2018/9, then shrank since

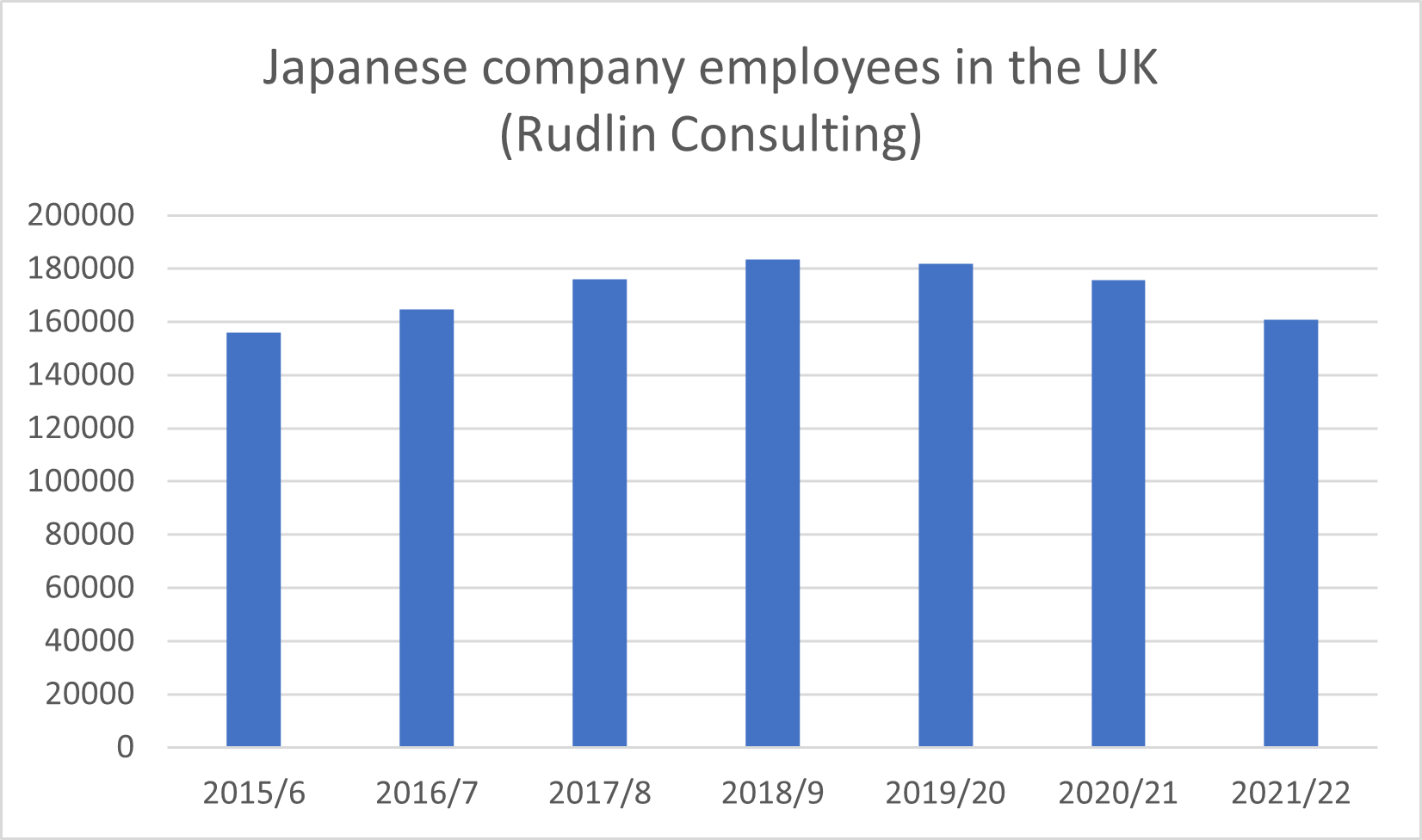

There were 98,000 people employed by Japan owned companies in the UK, according to the Toyo Keizai[1] database published April 2023, compared to 106,000 in 2015/6.

The Rudlin Consulting database, which includes more companies who have a Japanese owner through acquisition, shows around 160,000 employees for 2021/2, up slightly from 156,000 in 2015/6.

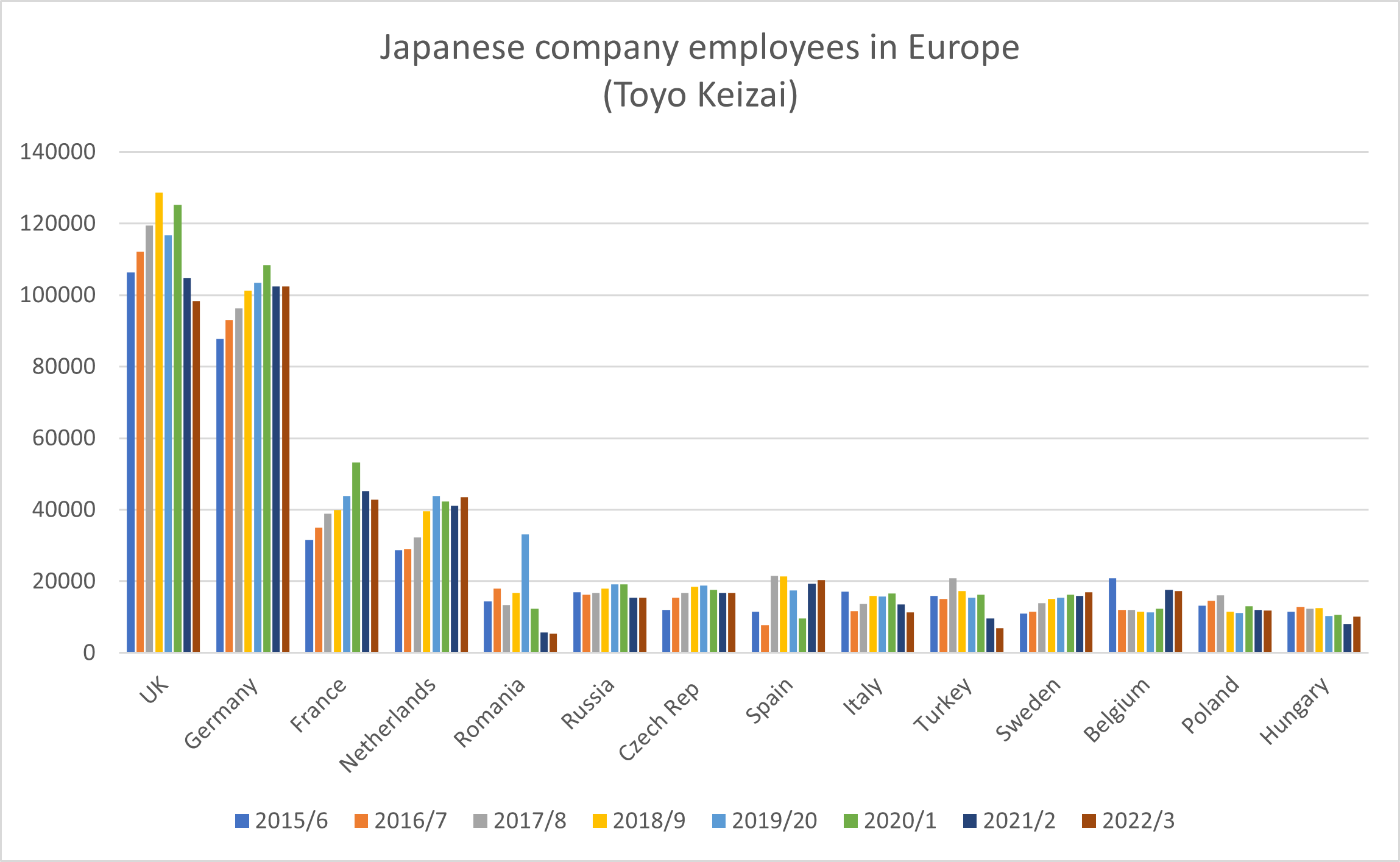

Both sets of data show that employee numbers reached a peak in 2018/9 and have fallen since. This is a different pattern to what has happened in France and Germany, where the employee numbers peaked in 2020/1, but have fallen since. The Netherlands shows somewhat bumpy growth.

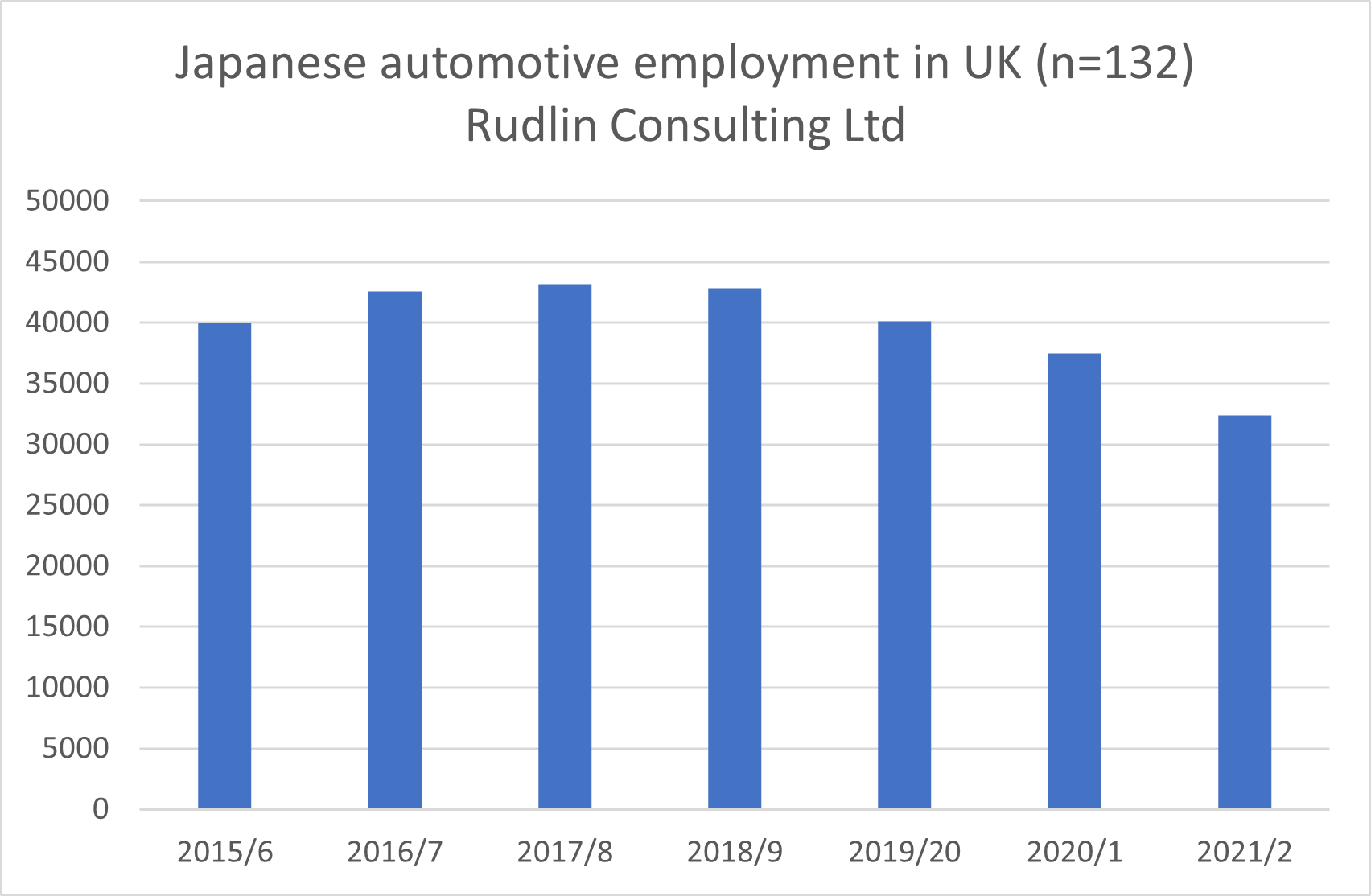

Looking at the employment data by sector, it seems the shrinkage in employment in the UK is almost entirely due to the decline in the automotive sector, where around 11,000 jobs have been lost in manufacturing and wholesale.

Germany has nearly caught up with the UK as a host of Japanese companies

Toyo Keizai estimates there were 875 Japanese incorporated subsidiaries in the UK in 2015/6 compared to 764 in Germany. By 2022/3 there were 982 Japanese incorporated subsidiaries in the UK, compared to 975 in Germany.

Rudlin Consulting estimates also include branches and more subsidiaries acquired through acquisition than Toyo Keizai. As of June 2023, we estimate there are 1,113 Japan owned organisations in Germany, compared to 1,151 in the UK.

More company closures in the UK than in Germany

48 companies closed in Germany since 2018 and 145 closed in the UK since 2017. The biggest sectoral net loss was in wholesale in the UK. A likely explanation is that many companies were dissolved or turned into branches, once they lost their European wholesale coordination functions, with warehousing and logistics focused more on the EU single market.

- 26 of the UK closures were in the automotive sector

- 41 were services

- 39 were wholesale

- 27 were manufacturing companies

- 11 were in the IT sector

- 9 financial

- 8 logistics

- 6 chemicals

- 4 retail

- 4 food

(some companies in multiple categories).

Many of these closures were due to consolidation and mergers, rather than outright withdrawal from the UK.

A similar number of new Japanese companies opened in the UK and Germany since 2017

64 new companies were established in Germany since 2017, compared to 63 new companies in the UK (of which 4 divested or closed since):

Of the 63 new companies in the UK:

- 35 were in the services sector

- 14 in wholesale sector

- 6 in IT

- 6 in the financial services sector

- 3 in manufacturing

- 3 in energy – storage, renewables, production

- 1 in logistics (following merger of container businesses of several Japanese companies)

- 1 in automotive (Highly Marelli, formed from merger with Calsonic Kansei)

(some companies in multiple categories)

UK still the target of Japanese M&A, but on a smaller scale than before

We have tracked 179 companies coming under Japanese ownership in the UK from 2017 to 2023 to date compared to 79 in Germany. These are not exhaustive numbers, and may well reflect a UK bias.

Furthermore, many of the acquisitions were not made directly of British or German companies, but rather of US or other European headquartered companies, which have subsidiaries in the UK or Germany. There may also be recent acquisitions which have not been identified yet.

With those caveats in mind, it does seem to be that majority (123 of the 179 UK acquisitions) were made over the three years from 2017-2019, and since then the rate has been more around 25 companies a year or fewer. There seems to be a similar trend in Germany.

The biggest acquisitions across Europe since 2017 have been:

- Takeda’s acquisition of Irish pharmaceutical company (London listed) Shire for $64bn in 2019

- Hitachi’s acquisition of Swiss company ABB’s Power Grids business for $11bn in 2020/2

- Renesas acquisition of US founded, UK domiciled semiconductor company Dialog in 2021 for $5.9bn

- Mitsubishi Corporation’s acquisition of Dutch energy company Eneco for $4.4bn

- Taisho’s acquisition of French pharmaceutical manufacturer UPSA SAS for $1.6n from Bristol-Myers Squibb.

- Hitachi Rail’s acquisition of Italy’s Ansaldo STS (1.5bn euros) from 2015 to 2019

- Nidec’s $1.2bn 2017 acquisition of Emerson Electric’s motors, drives and power generation businesses, which included the Welsh drives make Control Techniques and the French motor manufacturer, Leroy-Somer.

- Toyota Industries’ acquisition of Dutch logistics company Vanderlande for $1.3bn in 2017

- NEC’s acquisition of Danish IT company KMD in 2018/9 for $1.2bn

- Fujifilm acquisition of US company Biogen’s Hillerod manufacturing in Denmark for $930m in 2019

In the past, British companies have often been the target of the largest M&A deals, such as SoftBank acquiring ARM, NSG acquiring Pilkington Glass and various acquisitions in the financial services sector. This preference does not seem to have continued, apart from the Renesas/Dialog deal, although there have been smaller scale acquisitions in sectors such as recruitment and staffing, drives, tyres, food and paper wholesale in the UK.

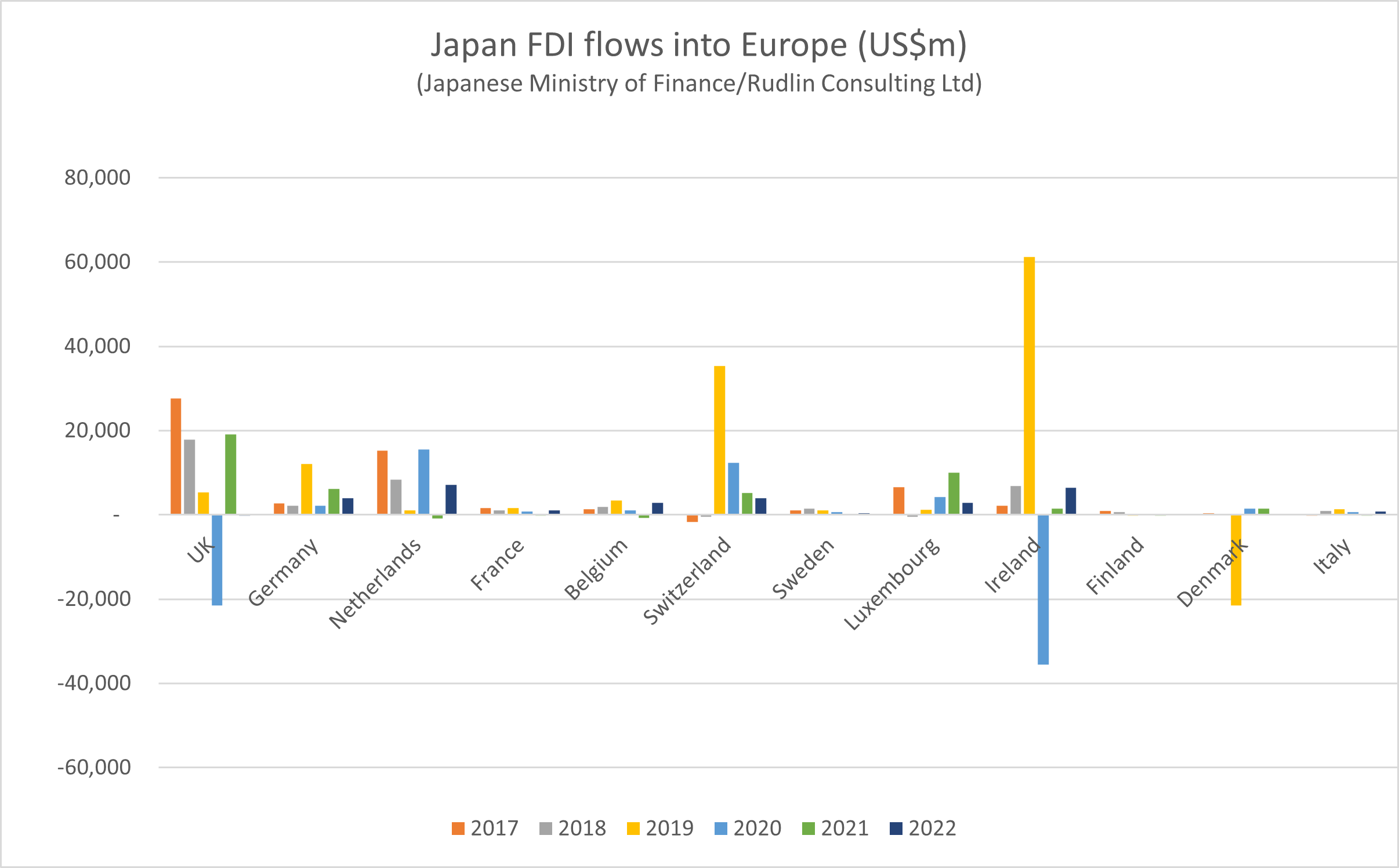

Switzerland overtakes the UK as largest net recipient of Japanese investment in Europe

These big deals have of course had an impact on the flow of investment from Japan into Europe, causing lumpiness in year-to-year totals.

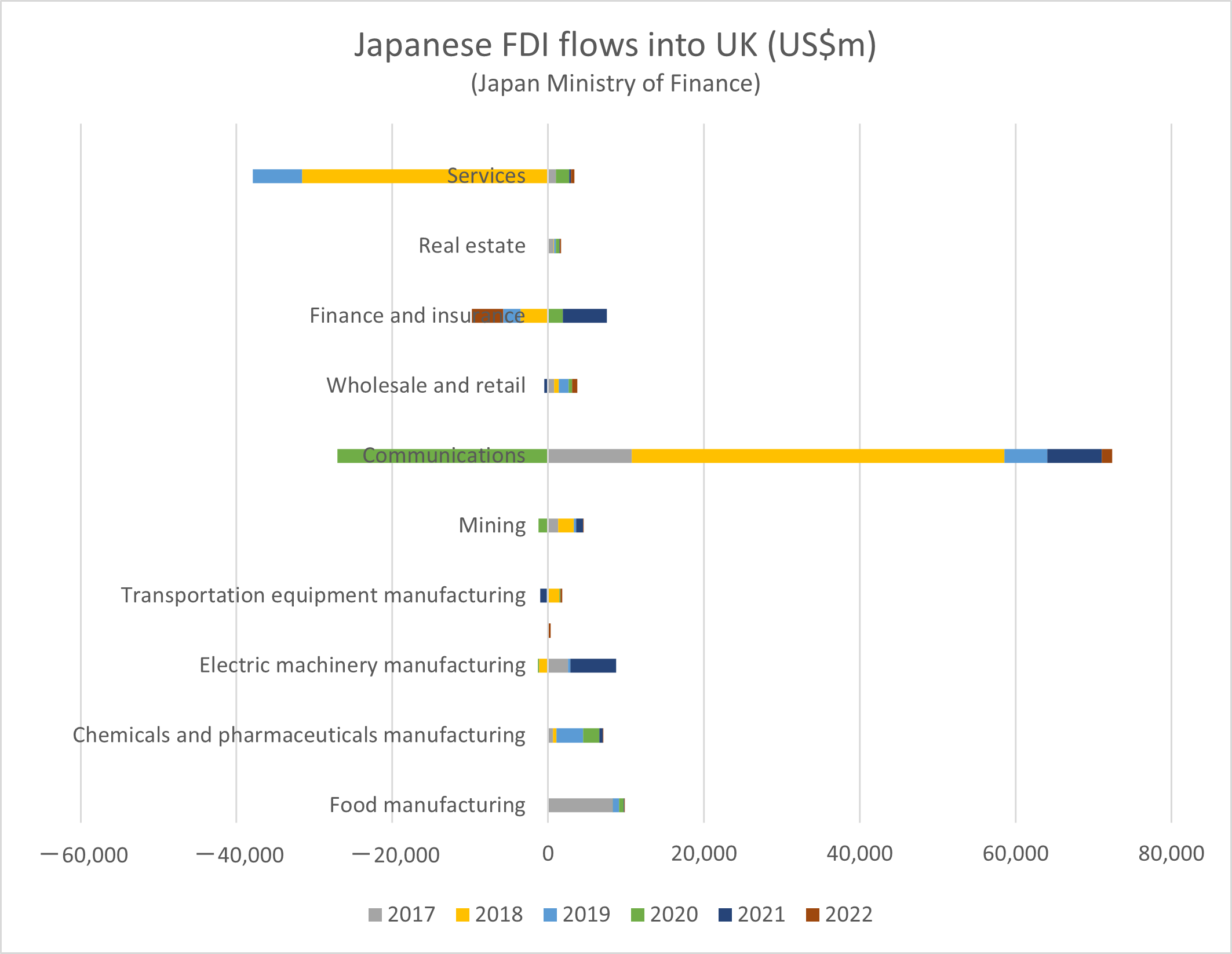

Switzerland received more cumulative net direct investment from Japan since 2017 than the UK, which was the largest recipient of Japanese investment in Europe in the past. The large inflow into Switzerland in 2019 in the wholesale and retail sector was presumably related to Hitachi’s acquisition of the ABB power grids business. The Netherlands was the third largest recipient and Ireland the fourth largest recipient.

The net divestment from the UK in 2020 was in the communications sector and may have been related to SoftBank, as much of their investment activities is located in London. There was also net divestment from the services sector in 2018. There were no major divestments by Japanese companies in terms of selling off subsidiaries in that year, so this might represent movement of assets from UK based subsidiaries to EU based subsidiaries as part of companies such as Sony shifting ownership their intellectual property rights.

In manufacturing, investment in UK electrical machinery, food and chemicals has been greater than the investment in transportation equipment (automotive) and substantially more than in German electrical machinery, food and chemicals manufacturing over the same period.

Cumulative Japanese direct investment totals for Germany and the UK in since 2017 are: [2]

| Sector | Germany | UK |

| Food manufacturing | $0.8bn | $9.8bn |

| Chemicals & pharmaceuticals manufacturing | $3.1bn | $7.1bn |

| Electrical machinery manufacturing | $0.6bn | $7.8bn |

| Transportation equipment manufacturing | $9.3bn | $0.8bn |

| Communications | $0.6bn | $45.3bn |

| Wholesale and retail | $2bn | $3.2bn |

| Finance and insurance | $8.2bn | -$2.3bn |

| Services | $1.2bn | -$34.5bn |

As can be seen below, Ireland has had both inflows and outflows in the chemicals and pharmaceuticals manufacturing sector in 2019 and 2020, presumably related to the Takeda/Shire deal. Denmark had an outflow in 2019, which may have been related to the sale by Takeda of two factories in Denmark to Orifarm.

The data from Japan’s Ministry of Finance needs to be treated with caution, as in many cases (France and financial services sector for example) no data is given, for confidentiality reasons.

Manufacturing employment holding steady, apart from the automotive sector

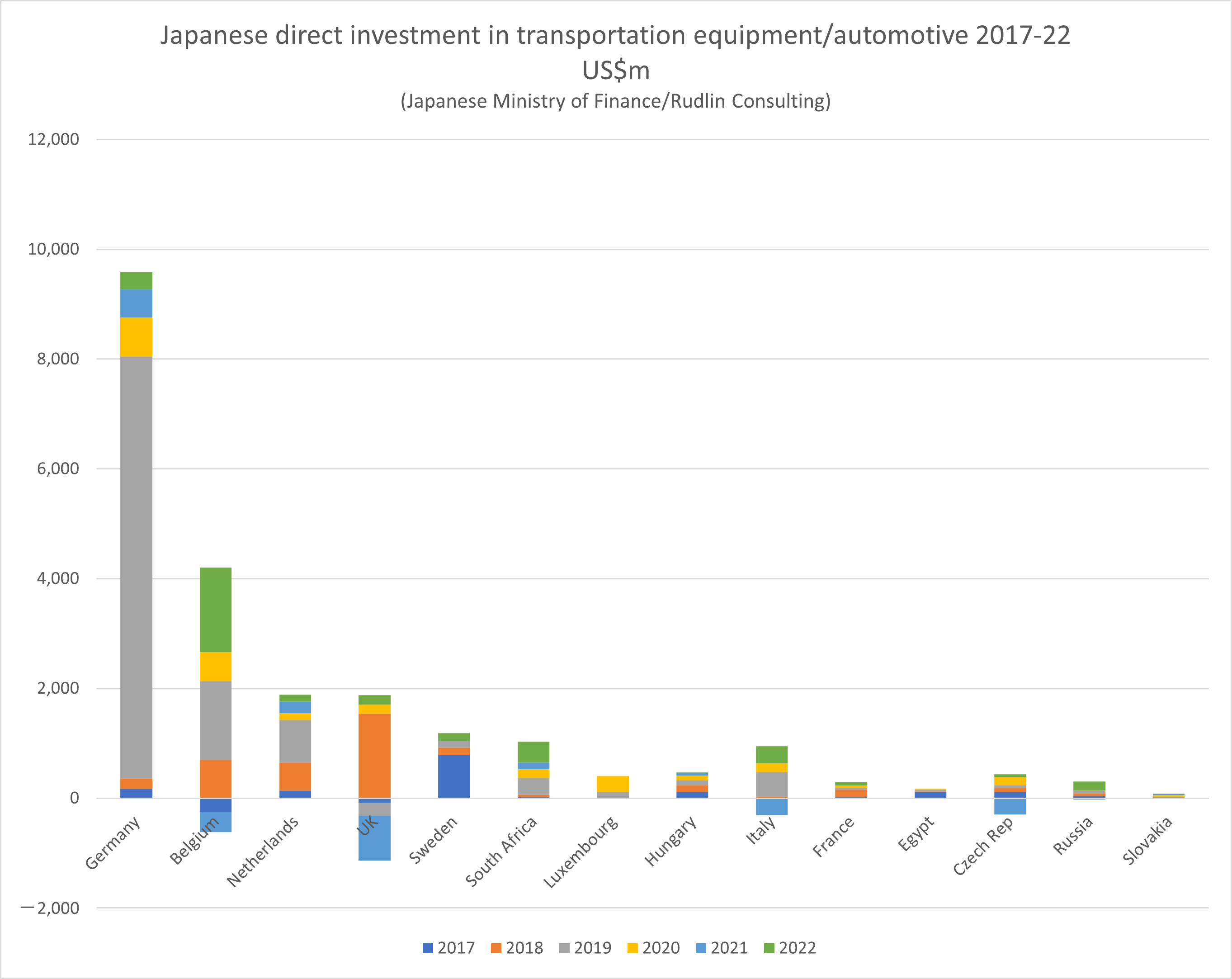

Disinvestment from the UK in the automotive sector in 2019 and 2021 was presumably related to the closure of Honda’s Swindon plant which was announced in February 2019 and finally shut down in July 2021. 20 or so Japanese automotive suppliers also ceased operations in the UK during this period.

Germany has benefited the most from Japanese investment in the automotive sector – the large inflow in 2019 may be related to Sekisui’s acquisition of Proseat’s European operations – with manufacturing in Germany, Poland and Czech Republic. The UK plant was closed in 2021.

There may have been some second hand investment in the UK automotive sector which is not reflected in the data. Belgium’s status as the second largest recipient of investment is almost certainly due to Toyota having their European headquarters there. Some of that investment may well then have made its way to Toyota’s plants in the UK.

The larger inflow of automotive investment into the UK in 2018 may have been related to Nissan starting production of the Juke at Sunderland in 2019 and then the third generation Qashqai.

Non-automotive manufacturing employment grew to 2019/20 and has held steady since. Most of the Japanese manufacturers we looked at set up Brexit committees, planned and invested for various scenarios. They must have come to the conclusion that the cost/benefit analyses showed it made more sense to stay put and invest in mitigation measures than to shut down and transfer manufacturing elsewhere.

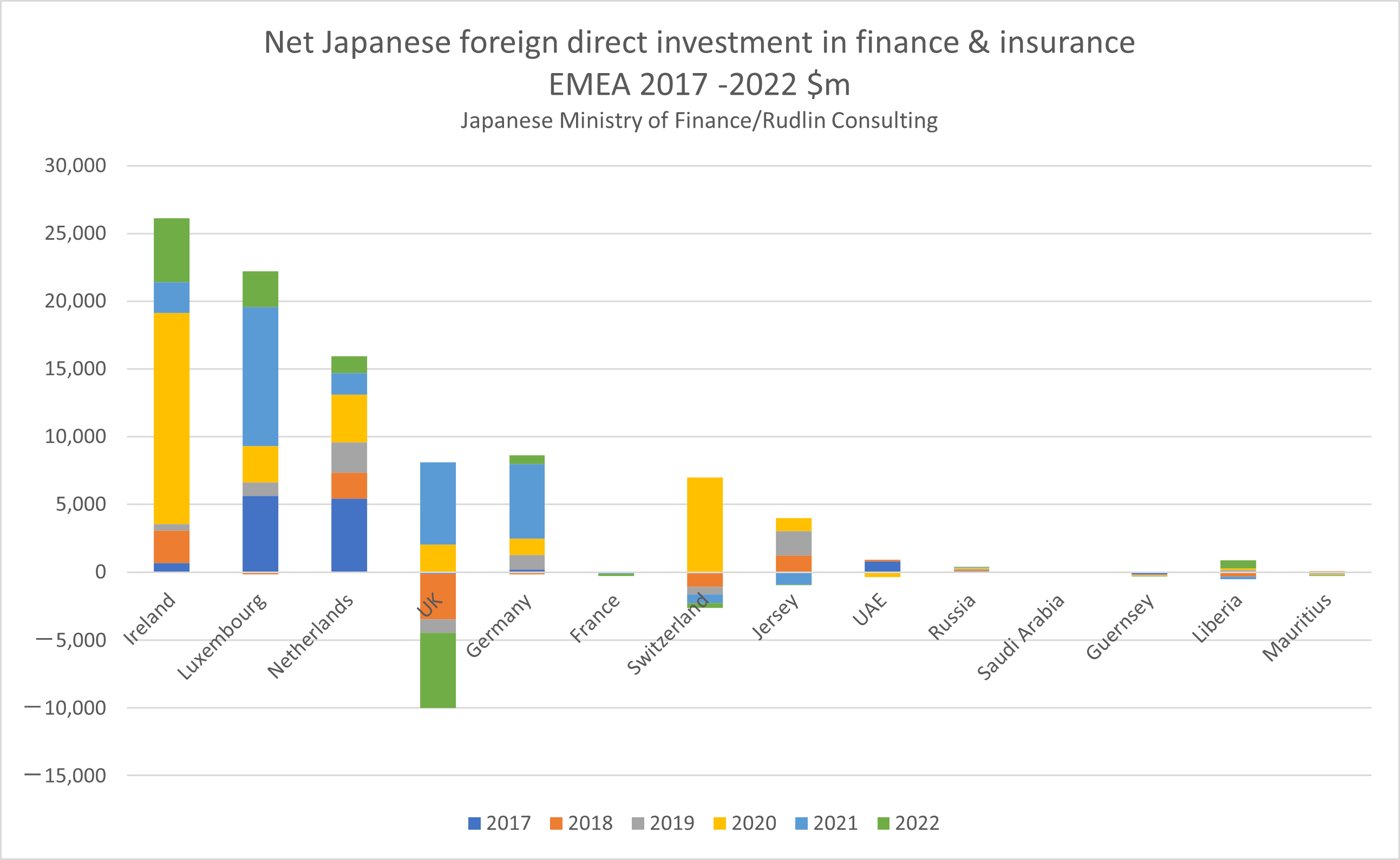

Net disinvestment in UK financial services sector, although employment remains steady

Although the cumulative investment by Japan into in the UK financial sector was negative from 2017 to 2022, according to Rudlin Consulting data, employment in this sector has held relatively steady. It is hard to be certain of this, as two of the three main Japanese banks are branches of the European headquarters in the Netherlands or the Japanese headquarters, so employee numbers are not disclosed.

Ireland has been a focus for Japanese aircraft leasing and related financing, which may explain why it has benefited most from Japanese financial services sector investment since 2017. For example, in 2020-2022, Japan Investment Adviser subsidiary JP Leasing Services set up a leasing company in Ireland with Airbus, acquiring several aircraft, which may account for the large investment in 2020.

Germany has overtaken the UK become the largest host to Japanese corporate expatriates in Europe

The general trend in Japanese corporate expatriation across EMEA is downward, and does not seem to have picked up after the pandemic, apart from in the Netherlands and the UAE. The shift of Japanese expatriates (largely based around London) is likely to be an indicator of regional headquarter functions shifting to Germany and the Netherlands, particularly in financial services and trading companies, where the density of Japanese expatriate staff is the highest.

What does it all mean? An acceleration of trends, new and old

I have, over the past seven years, tried to approach the data I gather on Japanese companies in the UK with an open mind. Nonetheless, I admit to having a Big Theory of Brexit (beyond believing it to be an unnecessary waste of time, effort and resources) which is that it accelerates trends which were already there.

So the question I wanted to answer, in looking at the data this time, was what trends were showing through, new and old.

In my history of Mitsubishi Corporation in London, examining how its business developed from 1915,[3] it became apparent that the organization had quite quickly moved from an importer/exporter trading model to a regional coordinator. It was following a well-known model of globalization in business to move from pure export to manufacturing locally and then to some kind of transnational model, with regional centers of excellence.

Japanese trading companies like Mitsubishi Corporation do not directly manufacture, but often invest in manufacturing, as Mitsubishi Corporation did, in acquiring Princes Foods in the UK in 1989. Primarily though, they are in London because they see it as an important global and regional hub, a good training ground for their rising stars to gather information and influence global policy making.

Just after Brexit became a reality, I remember attending a large gathering of senior executives of Japanese companies in the UK. The then head of Mitsubishi Corporation in Europe, Middle East and Africa spoke, making it clear that while he thought Brexit was a negative for Japanese business, the company would not be leaving the UK.

Having worked at Mitsubishi Corporation myself, including in planning and coordination, I instinctively understood this to be about the strategic value that a presence in the UK had for Mitsubishi Corporation, and other zaikai[4] Japanese companies. Nonetheless I worried that the UK’s strategic value to Japanese companies would diminish by no longer having as much influence in the EU once it was on the outside.

The only Japanese trading company to have left the UK since 2017 is Sojitz, which is not one of the top five of Mitsubishi Corporation, Mitsui, Sumitomo Corporation, Itochu and Marubeni. It has clearly decided to focus on chemicals trading, and to put that headquarters in Germany, which has traditionally been seen by Japanese companies as the regional leader in chemicals manufacturing.

Other regional headquarters to have left the UK were part of the earliest phase of globalization – the wholesalers who were importing from Japan. They have moved their regional coordination, warehousing and logistics hubs to the EU – which is why there has been significant growth in employee numbers and expatriate Japanese numbers in the Netherlands. At the same time, the overall drop in the number of Japanese expatriates across the region may well be due to how localized many of the wholesale operations have become in terms of senior management.

The second phase companies – those who opened manufacturing operations in the UK – have also shifted further out of the UK, and taken their supply chains with them. Consumer electronics manufacturing left some time ago, and the main concern had been for the automotive sector. As the analysis above shows, Germany has had by far the greater share of automotive investment in Europe since 2017, although this may be a one off, due to an acquisition. Some of the investment into Belgium may feed through to the UK via Toyota, however, and both Toyota and Nissan have not shown any signs of leaving the UK yet.

The third phase, of having regional coordination and centres of excellence, is showing through more strongly now for the UK. Now that the regional coordination which was more to do with supply chains for manufacturers, or logistics and warehousing for importing from Japan has shifted away from the UK, the UK is left with the geopolitically minded, strategic investors, in energy, transportation and telecommunications infrastructure, defence and R&D in biotech and pharmaceuticals and semiconductors.

These investors are not so influenced by the search for growth overseas which characterized Japanese acquisitions in the UK and elsewhere during the lost three decades of the 1990s to the 2010s. They are driven by geopolitical concerns regarding climate change and reducing dependence on hostile states in sectors such as telecommunications, energy and digital data.

Despite the current British government’s taboo on mentioning industrial policy, it is clear that many British politicians are aware of this new phase and realise that the UK’s concerns align with Japan’s. There has been an embarrassment of former and current prime ministers and ministers at recent UK-Japan events in London. The exhibition stands at the one I attended, as a non-executive director of a Japanese soft-power initiative, Japan House London, were almost exclusively focused on renewable energy.

The recent announcement[5] by the Japanese government that they will harmonise Japanese standards for domestically produced defence equipment with US and European standards, to reduce maintenance costs and increase business opportunities for Japanese defence companies is very much in line with this new third phase. The UK, Italy and Japan have merged their fighter jet programmes and are aiming to develop a next generation fighter jet demonstrator by 2027.

It is not going to be entirely smooth – Japanese trading companies have shown no inclination to disinvest from Russian LNG projects, for example. This will have been the subject of discussions with the Japanese government in terms of impact on Japanese dependency on foreign energy supplies – the Sakhalin 2 project, for example, supplies around 9% of Japan’s LNG imports.[6]

In terms of “making Brexit work” – for phase 1 and 2 companies, this ship has sailed as far as traditional import export, manufacturing related trade is concerned. They made all the contingency plans and moved what needed to moved a long time ago. There have been no new Japanese manufacturers setting up in Britain, and it is unlikely this will happen until the UK joins the single market again.

For phase 3, making Brexit work will be more to do with ensuring that cooperation and synchronisation with the rest of Europe and the UK’s positive influence inside and outside Europe is as strong as possible in the strategic areas of energy, defence, telecommunications and transportation infrastructure and R&D. This will not have the positive populist impact of phase 2 manufacturing projects, which bring thousands of jobs and supply chains in their wake. In fact the impact electorally could be negative, as we have seen with nuclear power, wind farms and high speed rail – there is antagonism towards the disruption to the countryside they cause and the massive investments they require. This is a problem familiar to Japanese companies in their home country too.

Furthermore, this collaboration is not just about Europe, it needs to bring in the neighbouring continents of Africa and the Middle East. Obviously climate change has to be tackled globally, it cannot be “environmentalism in one country”. Successive Japanese governments have worried about Japan’s energy poverty for decades and this has driven much of the investment, particularly by Japanese trading companies, in overseas energy projects. Trading companies have invested in Africa and the Middle East, often through their regional headquarters in the UK, in renewable energy projects ranging from hydroelectric power generation to solar home systems.

Japanese companies like working with other Japanese companies, so once a beachhead of investment is established, others in the supply chain and support system will follow – as the UK saw with Japanese car companies in the 1970s and the 1980s. That ecosystem is still strong in the UK and many of the components suppliers can also supply the energy and infrastructure sectors.

This new third phase of Japanese investment in and via the UK is not going to be attracted by the UK government giving grants to build or re-equip factories, but by it showing a willingness to invest for results which will only be seen in the long term, and to put political energy into building sustainable government policies and community support.

A pdf of this report can be downloaded here

Our latest 2023 directories of Japanese companies in the UK are available here.

[1] https://biz.toyokeizai.net/en/data/service/detail/id=860&academic=1

[2] https://www.mof.go.jp/english/policy/international_policy/reference/balance_of_payments/ebpfdii.htm

[3] The History of Mitsubishi Corporation in London: 1915 to Present Day Routledge Advances in Asia-Pacific Business, 2000 https://www.amazon.co.uk/History-Mitsubishi-Corporation-London-Asia-Pacific/dp/0415228727

[4] Zaikai means the Japanese business and finance community, particularly those companies with power and influence and connections to the political sphere, which are seen as representing Japan in the world.

[5] https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/Aerospace-Defense-Industries/Japan-to-standardize-arms-with-U.S.-Europe-for-joint-maintenance accessed 22 June 2023

[6] https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/japans-mitsui-says-no-plans-exit-russias-sakhalin-2-lng-project-2023-06-21/

For more content like this, subscribe to the free Rudlin Consulting Newsletter. 最新の在欧日系企業の状況については無料の月刊Rudlin Consulting ニューズレターにご登録ください。