Mitsubishi Electric’s introduction of a system that will allow employees to work virtually in one country, while being based in another was described as an “evening scoop” by the Nikkei newspaper. The Nikkei then went on to position it as being aimed at employees based outside Japan, who can then work in Japan headquarters, thereby enabling Japan HQ to exert a more centripetal force on the rest of the world.

I am not quite sure how much of a scoop this really is, as I already experienced a similar system, along with many other members of “Global” when I worked at Fujitsu in the UK ten years ago – I had an international role but my salary, tax and benefits were all paid as if I was a UK based employee. The UK operation was compensated for this by Japan headquarters.

The solution to Japan’s demographic crisis?

My second doubt about this is whether this is really the solution for Japan’s demographic crisis. Japan needs immigrant workers because of its declining birth rate, in addition to which Japanese companies often talk about the importance of cultural diversity in their corporate headquarters, but nobody seems to want the hassle of actually allowing foreigners into the country to live. Only very specific categories of jobs can add value entirely through remote working – no surprises that Pasona, a Japanese staffing services company, has an offering to cover remote work from overseas – for foreign IT workers. If the aim is to add value to headquarters’ decision making and creativity through diversity, then some face to face, daily interaction is going to be needed.

When I first saw the Nikkei headline, I thought Mitsubishi Electric’s new system was going to be for Japanese managers who need to manage overseas subsidiaries, but would rather do it remotely, than uproot their families to move abroad for five years or go solo or tanshinfunin, as it is known in Japanese. Expatriation is costly for the employer too. This is mentioned in the article, but as a secondary aim.

Or increasing localization?

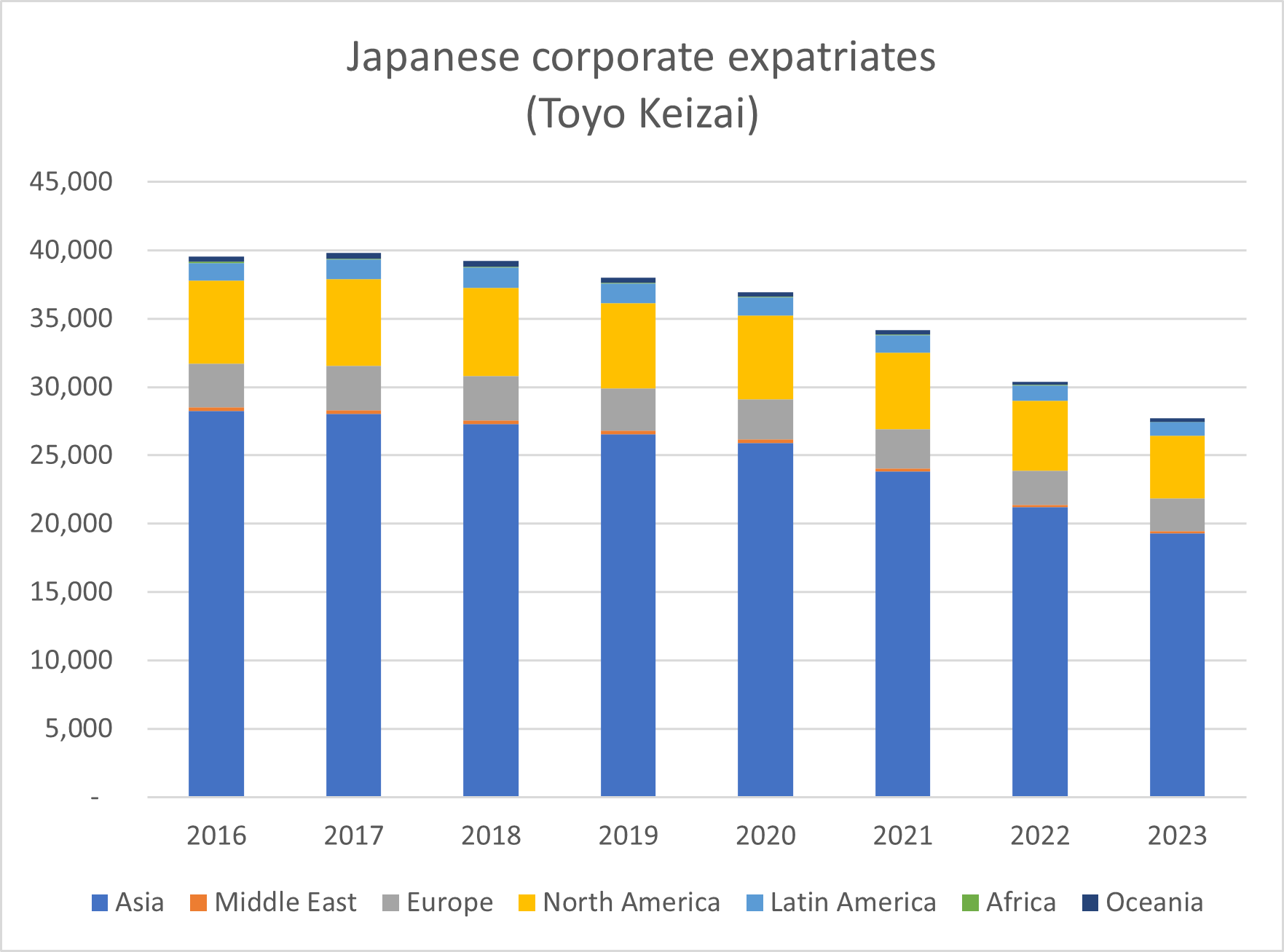

Many other Japanese companies may be adopting similar systems, or just relying more on local managers to run things – as we noted in a previous article. As a consequence, there has been a 30% drop in the number of Japanese corporate expatriates since 2015/6, according to Toyo Keizai. North America had the smallest drop in numbers (-24%) and Oceania the highest (-43%). The numbers of Japanese corporate expatriates in Europe fell 27% since 2015/6, and the total is about half that of North America. The decline set in before the pandemic, but certainly seems to have been accelerated by the inability to move people around the world, and the discovery that it was possible to oversee, if not hands-on manage, overseas operations remotely.

Many other Japanese companies may be adopting similar systems, or just relying more on local managers to run things – as we noted in a previous article. As a consequence, there has been a 30% drop in the number of Japanese corporate expatriates since 2015/6, according to Toyo Keizai. North America had the smallest drop in numbers (-24%) and Oceania the highest (-43%). The numbers of Japanese corporate expatriates in Europe fell 27% since 2015/6, and the total is about half that of North America. The decline set in before the pandemic, but certainly seems to have been accelerated by the inability to move people around the world, and the discovery that it was possible to oversee, if not hands-on manage, overseas operations remotely.

Toyo Keizai’s data on corporate expatriates relies on self reporting through their surveys, so undoubtedly underreports the true number of expatriates. It is at least a consistent data set, with few anomalies, so the trend seems clear. It only records 6 Japanese expatriates for Mitsubishi Electric in Europe and Africa, and another 7 in the Middle East – the former seems very low.

Mitsubishi Electric operates in more than 40 countries around the world, with overseas sales accounting for 50% of consolidated sales and 40% of consolidated employees (approximately 146,000). 11% of its sales and around 9,500 (6.5%) of its employees are in the Europe, Middle East and Africa region. We had to estimate the 9,500 figure ourselves, as Mitsubishi Electric does not disclose regional breakdowns of its employees. If remote working across country borders really becomes dominant, at least at managerial rather than shopfloor level, then such data will become increasingly meaningless anyway.

Breaking it down for EMEA

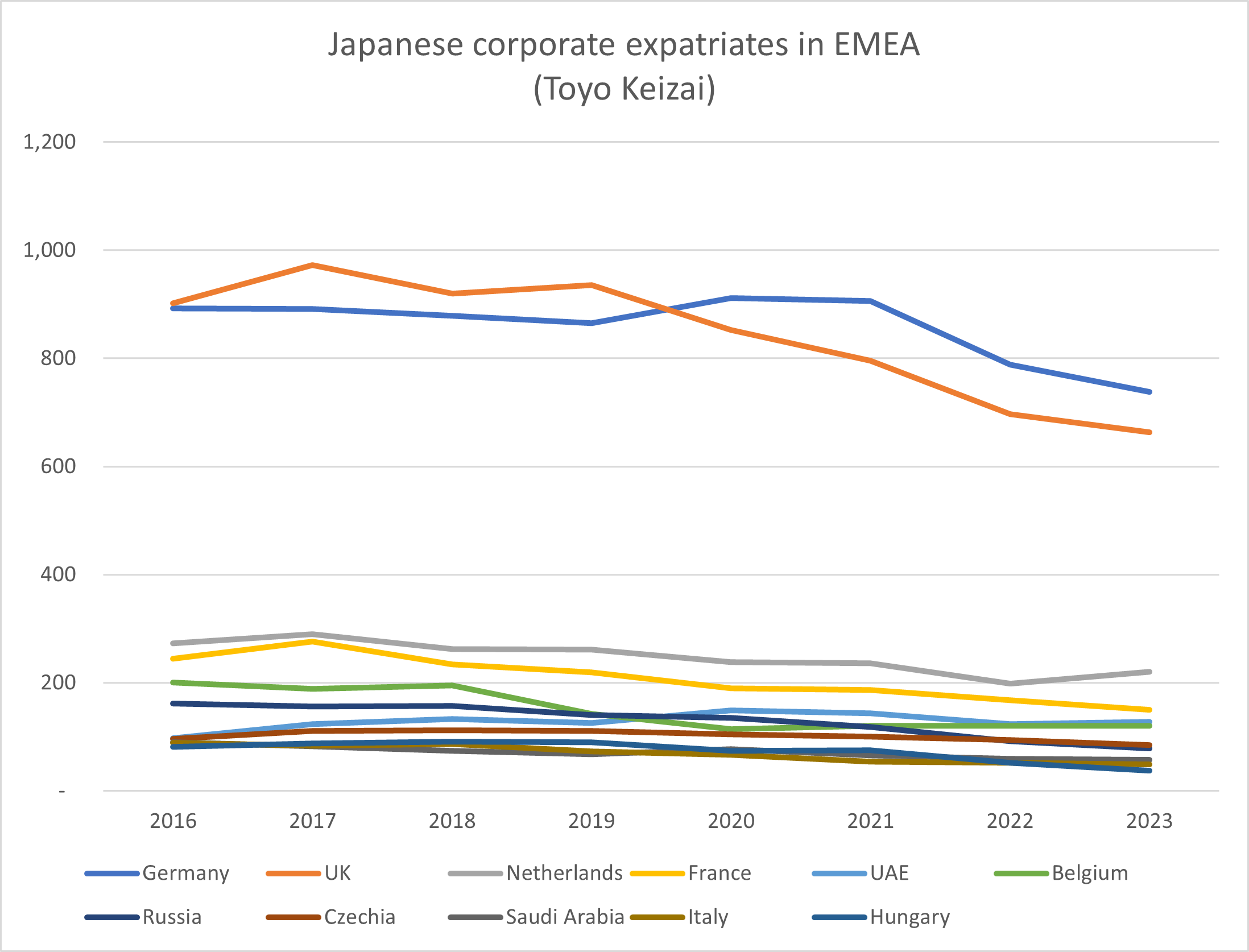

Looking at the Toyo Keizai data for individual countries in Europe and the Middle East shows that the only country to show any positive growth in Japanese corporate expatriate numbers since 2016 is the United Arab Emirates. The fall in Japanese expats in the Netherlands (-19%) was not as steep as elsewhere in EMEA (-27% average, -26% for UK, -40% for Belgium ) and seems to be recovering a bit since the pandemic. The number of expats in Germany also fell by only 17% since 2016, having grown and surpassed the UK in 2019/20, but falling steeply since the pandemic began, with no signs of recovery yet.

Looking at the Toyo Keizai data for individual countries in Europe and the Middle East shows that the only country to show any positive growth in Japanese corporate expatriate numbers since 2016 is the United Arab Emirates. The fall in Japanese expats in the Netherlands (-19%) was not as steep as elsewhere in EMEA (-27% average, -26% for UK, -40% for Belgium ) and seems to be recovering a bit since the pandemic. The number of expats in Germany also fell by only 17% since 2016, having grown and surpassed the UK in 2019/20, but falling steeply since the pandemic began, with no signs of recovery yet.

For more content like this, subscribe to the free Rudlin Consulting Newsletter. 最新の在欧日系企業の状況については無料の月刊Rudlin Consulting ニューズレターにご登録ください。