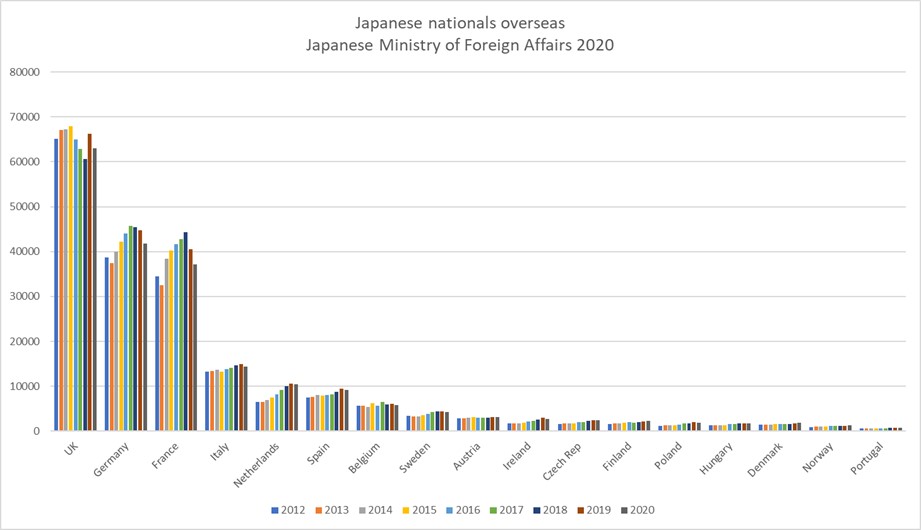

The number of Japanese nationals resident in Western Europe had grown steadily over the past seven years to reach over 220,000 by 2019. But by October 2020, according to Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, that number had dropped 5% to around 212,000. Of course the pandemic may have been an influence on this, evidenced by the fact that the number of Japanese residents overseas fell consistently around the world, with a global decline of 3.7% from October 2019 to 2020. But the latest statistics also show that some longer term trends continue and that the UK, while dominant as a host of Japanese companies and nationals, is also something of an outlier.

I’m surprised the numbers only fell 5% in Western Europe, as anecdotally I had heard of Japanese managers who were supposed to be moving to Europe staying in Japan, and ending up doing European working hours, trying to do their coordination job in a Japanese time zone. I have a sinking feeling they were also glued to their laptops during Japanese working hours too.

The fall in numbers of Japanese nationals resident in the UK had been a long term trend since 2015, but had shot back up in 2019. Since Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs stopped giving breakdowns by visa category in 2017, it’s hard to work out what was behind this decline. It seems likely as I mentioned in previous posts, that it was more to do with how student visas were classified, with a secondary impact of Brexit on corporate expatriation to the UK.

The number of Japanese nationals in the UK fell 5%, the Western European average, from October 2019 to October 2020, compared to an 6.7% drop for Germany and an 8.4% drop for France. The UK is still the biggest host of Japanese nationals in Europe, with 63,000, compared to Germany with 42,000 and France with 31,000.

The Nordics buck the trend?

Some European countries hosted more Japanese nationals in 2020 compared to 2019 – mostly the Nordics – Finland, Norway, Denmark – and Austria. If this was anything to do with which countries were safer in the pandemic, this must have been more to do with perception than reality, as no country in Europe had been particularly badly affected until November 2020, just after the statistics were collated.

As the Financial Times charts show, in the winter of 2020, UK, Austria and Denmark all had a higher number of cases and the UK and Austria had a higher number of deaths than the European Union average. But it does seem that Norway and Finland were good choices in terms of staying healthy.

The rising phenomenon of non-resident Japanese directors

I’ve also seen a rise in Japanese directors of UK companies, who used to be resident in the UK, now being resident in the Netherlands. Although the Netherlands is still a much smaller host of Japanese nationals than the UK, Germany or France, the trend for Japanese nationals resident there is strongly upwards, with only a slight (-1%) downward turn in 2020.

Maybe the trends and impact of coronavirus will become clearer when the statistics for October 2021 are published in autumn of next year. It may turn out that COVID-19 accelerated trends that were already there, of consolidating and reducing the number of Japanese corporate expatriates, as Japanese directors and managers of UK and other European Japanese companies decided that they can manage their European subsidiaries remotely.

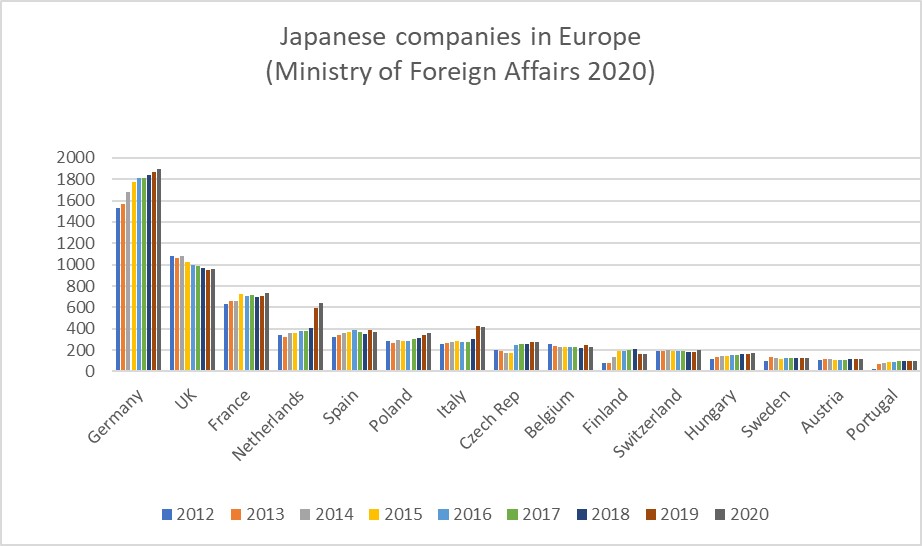

Turning to the statistics for Japanese companies in Europe, the rise in the number of Japanese nationals in Netherlands clearly has something to do with the numbers of Japanese companies in the Netherlands shooting up these past two years. I had previously speculated as to what was the cause of the sudden rise in Japanese companies in the Netherlands and also Italy. Both have continued at that level for 2020, so it was clearly not a glitch and more a rebasing or redefinition of what counted as a Japanese company as there is no evidence that a sudden jump in the number of new Japanese entrants happened in either country.

The UK managed to claw back some of the 12% decline in the number of Japanese companies it hosts since 2012, but is the only country in Europe, along with Belgium, to show a decline over the 9 years, when the numbers rose 23% on average for the whole of Europe. As we have outlined before, this decline is less about a complete withdrawal from the UK, and more about some long overdue tidying and consolidation, accelerated by Brexit, of shifting European regional bases to the continent and turning UK subsidiaries into branches.

For more content like this, subscribe to the free Rudlin Consulting Newsletter. 最新の在欧日系企業の状況については無料の月刊Rudlin Consulting ニューズレターにご登録ください。