Japanese companies and nationals are continuing to come to Europe, but…

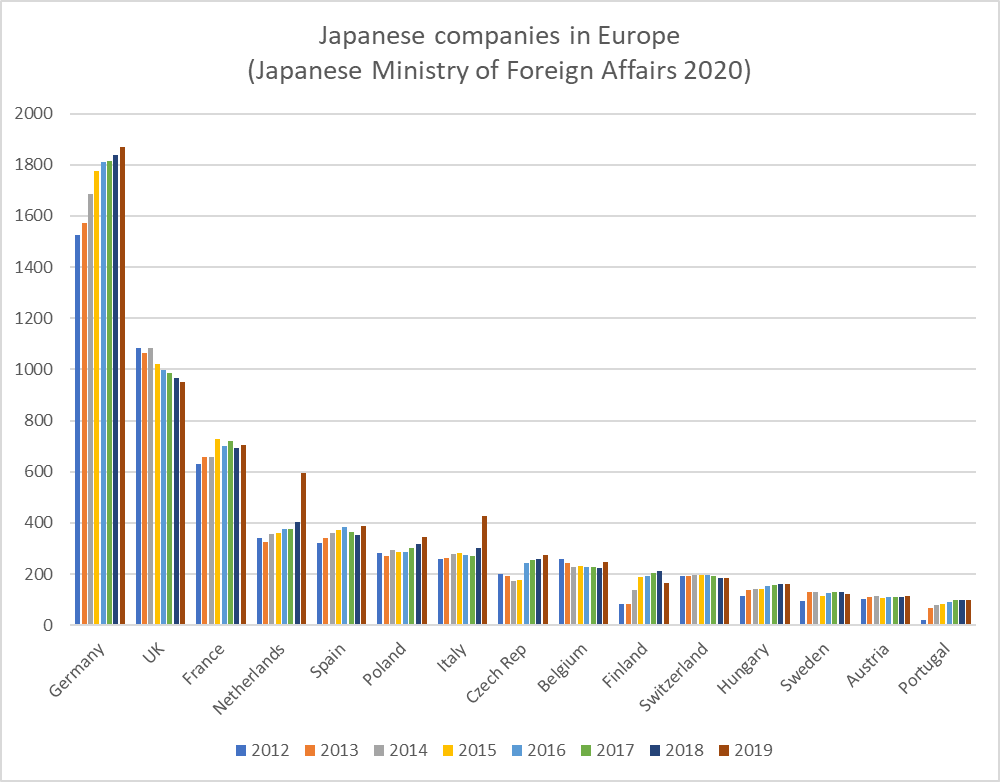

The chart below tells the main story of recent movements in the presence of Japanese companies in Europe pretty clearly. An ever increasing number of Japanese companies (including branch offices and joint ventures) are appearing in Europe, whether through greenfield investment or acquisition. The only two countries in the top 15 hosts of Japanese companies which have seen a decline over the past five years in the number of Japanese operations on their territory are the UK and Switzerland.

Italy and the Netherlands have seen big leaps in the numbers of Japanese companies operating within their borders. Germany continues to dominate, hosting over 1800 Japanese operations, nearly double the next biggest host, the UK. France is the third largest host, but seems stuck around the 700 mark.

Although they were not released until September 2020, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) figures are for October 2019. However they tally in some ways with the story told by the December 2020 JETRO survey of Japanese companies in Europe which we blogged about here. According to that survey Poland, Germany and Hungary and the Czech Republic are seen as the most promising sales destinations and importing from Japan under the EPA was particularly focused in the Czech Republic, Netherlands, Belgium, Italy and Germany for 2021. Italy’s 2019 leap may be squashed back down in 2020, as Italy, UK, Sweden, France and Hungary were the countries in which Japanese companies thought their business would shrink. For Italy this may be to do with the impact of the coronavirus epidemic.

Unfortunately MOFA has changed the way it compiles – and it would seem classifies – these numbers. Digging into the detail of why numbers in Italy and the Netherlands shot up from Oct 2018-Oct 2019 shows that in Italy there was a large rise in the number of locally incorporated subsidiaries and branches (as opposed to branches of the Japan HQ or joint ventures). In the Netherlands there was a decrease in the number of headquarter owned branches and locally incorporated companies and their branches, and a rise in the number of “unclassified” from zero to 394.

The sudden rise in the number of companies and branches owned by Japanese companies may have something to do with Hitachi acquiring various Ansaldo rail businesses from Finmeccanica in Italy. Similarly, MItsubishi Corporation acquired Dutch energy company Eneco, which may have entailed taking on a large number of subsidiaries and branches. It seems clear the Netherlands was the favoured destination for Japanese companies looking to relocate headquarters functions, particularly in services, sales and logistics, as a Brexit back up.

Japanese nationals in Europe

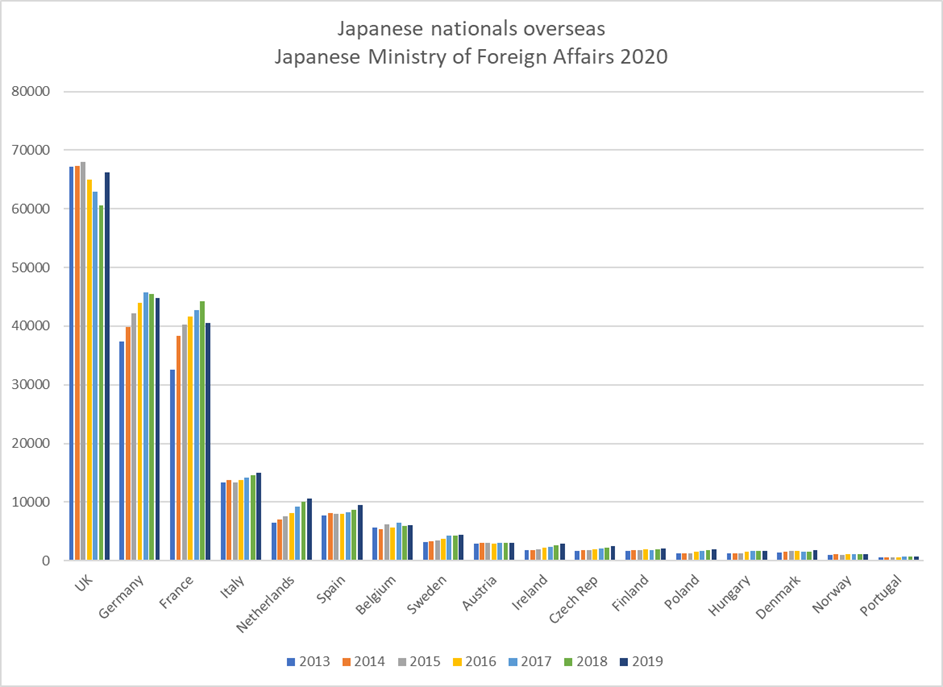

MOFA have also changed the way it compiles statistics on Japanese nationals overseas. Until 2017 the data included categories for permanent residents, intra company transferees, media, entrepreneurs, academics and students etc. But from 2018 the number is only broken down into long term residents and permanent residents.

How students are categorised also seems to have changed, and this has impacted the UK in particular – possibly because the UK itself also changed visa categories recently, particularly how students or trainees studying in the UK for less than a year are treated. For the last available year, 2017, the numbers of students and other academia related Japanese nationals had fallen by nearly 5,000 since a peak of 21,035 in 2014 in the UK. But student numbers had increased over the same period for other European locations and in Australia, New Zealand and Canada, with a small decline in the USA.

This fall in the number of students was a major contributor to the overall decline in the numbers of Japanese nationals in the UK from a peak of around 68,000 in 2015 to 62,887 in 2017. Intracompany transfers had also been declining since a peak of 19,552 in 2013, to 17,752 in 2017.

The surprise of the 2019 data released by MOFA in October 2020 is that the number of Japanese nationals in the UK has shot up again, after 3 years of decline. In October 2018 there were 60,620 Japanese nationals in the UK but this rose to 66,192 as of October 2019. As no further detail is provided, it could be that some students and company trainees are now being counted as long term residents again. As the number of Japanese companies has declined, the only other explanation is that 6,000 more Japanese students decided to come to the UK in 2019 compared to the previous three years or so.

Conversely there has been a decline in the number of Japanese nationals in Germany for the second year running and a significant drop in the number of Japanese in France, whereas Italy, Netherlands and Spain have all showed a rise in the number of Japanese resident there.

The overall trend for Europe is positive – a 15% rise in the number of Japanese nationals resident in the region since 2013 to around 234,000 (95% of them in Western as opposed to Eastern Europe) and a 19% increase in the number of Japan owned companies in Europe to around 8,000 since 2013. The rate of increase has been the same for both Western and Eastern Europe. In the past three years the rate of increase has been slightly faster in Eastern Europe. 79% of Japanese companies in Europe continue nonetheless to be based in Western Europe, suggesting that the trend is for existing Japanese companies in Western Europe to open additional operations in Eastern Europe.

For more content like this, subscribe to the free Rudlin Consulting Newsletter. 最新の在欧日系企業の状況については無料の月刊Rudlin Consulting ニューズレターにご登録ください。

Read More LinkedIn

LinkedIn YouTube

YouTube