[playht_player width=”100%” height=”175″ voice=”Lily”]My view on Brexit was that it was accelerating trends that were already there for Japanese business in Europe, and gave them cover to do things they were already wanting to do.

The COVID-19 pandemic seems set to provide similar cover and if the UK is not careful, this will mean a further withdrawal of Japanese investment from the UK.

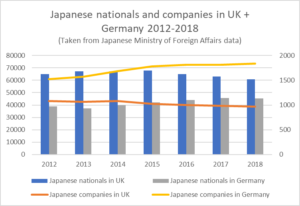

Japanese companies are still in search of growth outside the ageing, declining population of the Japanese market, and this includes in Europe. According to Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs data, the number of Japanese companies in Europe grew 16% from 2012-2018 and the number of Japanese nationals in Europe also grew over the same period by 12%.

At the same time Japanese companies are very risk averse. Brexit was seen as a risk from around 2013 onwards, and this is reflected in the number of Japanese companies and nationals in UK falling by 11% and 7% respectively over 2012-2018 – the only country in Europe to show such significant decreases. Germany already hosts more Japanese companies than the UK and is catching up in terms of hosting Japanese nationals too.

Although Japan is still more of a manufacturing, exporting nation than the UK is, both the UK and Europe are just as – if not more – important to Japan as a destination for investment than as a market for exports of finished goods. As the DIT itself estimates, around 59% of Japanese exports to the UK are intermediate goods, used in supply chains. So in other words, a large number of Japan’s investments in the UK and the Europe boost Japanese exports to the UK and Europe.

The trends in current Japanese trade and investment in Europe and the UK need to be examined for their impact in the four areas where Japan has influence over the UK economy

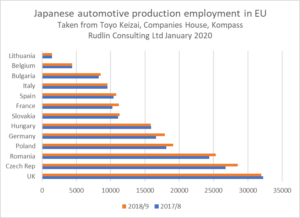

1. Existing UK jobs reliant on Japanese companies

The Japanese automotive sector is a key source of existing jobs for the UK as it accounts for around a quarter of the 163,000 people I estimate are employed in the UK by Japanese companies. There was a 3% decline from 2017/8 to 2018/9 in employment in the Japanese automotive sector in the UK, however, whereas employment in Japanese automotive companies grew elsewhere in Europe, particularly in Eastern Europe.

So while zero tariffs on automotive parts from Japan to the UK will help – this might just be trying to hold back the tide. The possibility of tariffs on exports of cars made in the UK to the EU is obviously a concern for Japanese companies too. Maybe sterling will fall far enough or there will be sufficient government subsidies to mitigate this extra cost but ultimately Japanese companies will choose to manufacture where there they can access not just the lowest costs but also a market sufficiently large to ensure full production capacity.

Obviously there is a strong need to focus on electric vehicle development, and the UK has strength in automotive design, but Japanese car manufacturers will be wanting to develop EVs in line with EU regulations and to be able to influence EU regulations – which is easier done from inside the EU than outside.

2. Where the new Japanese jobs are in the UK

Hitachi is the most significant recent contributor to organic job growth in Japanese companies in the UK – largely due to Hitachi Rail. Hitachi has also invested in Horizon Nuclear Power, which is currently “on ice”. Hitachi’s focus is on social infrastructure, and various commitments by UK governments on investing in transportation and energy are key to this. Many other Japanese companies are also interested in social infrastructure business in Europe.

A UK Japan trade agreement can support further job growth by facilitating the export of parts for these industries from Japan. Hitachi has also invested in rail manufacturing in Italy so if there are any tariffs making exports from the UK to the EU uncompetitive, they have an alternative manufacturing location within the EU.

Other Japanese companies that are expanding in the UK include NTT, the ICT/telecommunications giant, who have put their non-Japan global HQ in London and SoftBank, who acquired ARM and committed to expand the workforce. Presumably this is why DIT is emphasizing free data flows between Japan and the UK, which would be welcomed by Japanese ICT companies and Japanese regional headquarter functions based in the UK.

I’m seeing some positive impacts of the EU-Japan EPA on investment elsewhere in Europe. There have been quite a few acquisitions by Japanese companies of food businesses in France for example. Japanese trade statistics show that food and alcohol exports to Japan from Europe have risen after the EPA came into force. If a similar agreement on food, textiles and leather goods to the EU Japan EPA is reached between Japan and the UK as the DIT is asking, there may be similar acquisitions by Japanese companies in the UK – as well as the growth in exports for UK SMEs that the DIT seems to be focusing on. There already have been a few food related acquisitions by Japanese companies in the UK. This might see some increase in new jobs in the UK as a result. But this is marginal compared to the jobs that could be created by Japanese investment in the UK infrastructure sector.

3. UK exports of services to Japan are M&A driven

It seems likely that Japanese companies will continue to use their piled-up cash to acquire – perhaps in Asia initially as it is opening up first after COVID-19. In the past, Japan established companies in the UK as gateway to EU but recent Japanese acquisitions in the UK have been increasingly pure domestic (recruitment, car parking, outsourcing, advertising) or pure global (SoftBank, financial services).

These acquisitions do not necessarily create more jobs, but financial, legal and other services around the acquisitions is, I would guess, a large component of UK services exports to Japan. Allowing UK professionals to operate in Japan is not a key driver – it is more that UK based professionals are supporting Japanese companies in Europe and globally. I even know of one UK based, American owned advertising agency that deals directly with the Japan HQ of a Japanese sports brand on their global campaigns, even though the advertising agency have a Japanese office.

Japanese companies may well buy up more British companies in the near future, as they will be cheap. However, there does seem to be a decline in big ticket acquisitions in the UK – the most recent major European acquisition by a Japanese company that I am aware of is Mitsubishi Corporation acquiring the Dutch Energy company ENECO – my understanding is that Netherlands based services companies mainly supported this.

4. Export of services because of UK as European/EMEA hub

Another element in the UK’s export of services to Japan is that the UK subsidiaries of Japanese companies often perform a regional headquarters function for Japanese firms – and receive management fees for this. Brexit (but also changes in Japanese laws on treatment of offshore profits) has caused some Japanese companies to move their regional HQ from UK (Panasonic, Sony) in a legal and financial sense. But there is still a critical mass of people in the UK working for such companies, because the UK provides marketing, IT, design, engineering, legal, financial, accounting services that are of a high, globally accepted standard.

This is why, as the JETRO survey of 2019 of Japanese companies in Europe pointed out, the biggest regulatory concern of Japanese companies is that the UK or the EU might change regulations regarding the freedom of movement between the UK and EU for their employees. Continuing that regional coordination role requires regional employees to move around the region – or can this all now be done by web conferencing?

The UK is still seen by Japan as an attractive place to send students but also employees for education and development. Japanese students only want short term, under 1 year courses, however and many are looking at cheaper, nearer options. Both students and Japanese professionals would want ease of acquiring visas, including work visas and a safe, stable environment to live in.

UK offensive interests

Looking at the recent DIT paper on the UK-Japan FTA, clearly there are some non-tariff barriers to the UK accessing the Japanese market – as there have been for decades. But my overwhelming impression is that most British companies have not been very proactive in approaching the Japanese market – it’s a big commitment, opening an office in Japan is needed, not just exporting from afar. It’s relatively easy to set up a company in Japan but not so easy to hire the right people. There is a labour shortage, particularly of capable salespeople who are English speakers. This is not something that can be solved in a trade agreement.

A final point regarding the DIT paper’s claim that the UK is a “technology superpower” – not in Japanese eyes I’m afraid – possibly in fintech and there have been some Japanese investments in that sector in the UK. But they’re fairly small scale. Japanese technology companies such as Panasonic are basing their innovation arms in Silicon Valley. The US, China and the EU are more important to Japan than the UK – in many ways.

For more content like this, subscribe to the free Rudlin Consulting Newsletter. 最新の在欧日系企業の状況については無料の月刊Rudlin Consulting ニューズレターにご登録ください。