Japanese companies in the UK are shrinking – is Brexit to blame?

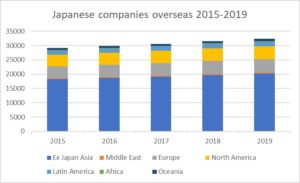

The number of Japanese companies and their employees in the UK is starting to decline. Given that this is against the trend elsewhere in Europe, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that this is a reaction to Brexit.

Brexit has put up barriers to the UK trading within the Single Market, damaging sectors it used to have a comparative advantage in such as automotive manufacturing and financial services. The UK is now left with its global strength in services such as professional services, IT, design, marketing and education. It remains to be seen how much of this strength was also reliant on being part of the Single Market, in terms of being able to sell those services to the EU and benefit from the freedom of movement of the people providing or benefiting from those services. So far, Japanese companies seem to be happy to continue to access these services by basing their regional head offices in the UK, regardless of Brexit, or through acquiring British companies in the services sector.

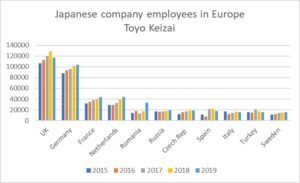

The decline is from a high base. The UK has the highest stock of Japanese foreign direct investment, the highest number of employees of Japanese companies, and the most resident Japanese nationals in Europe.

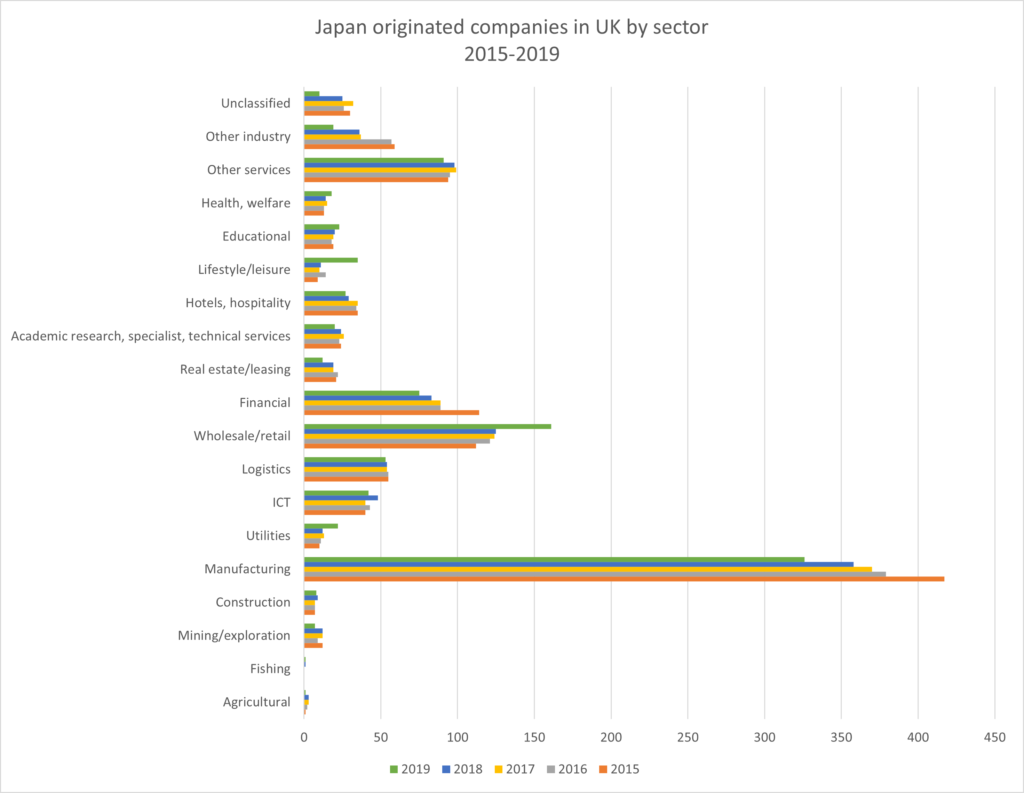

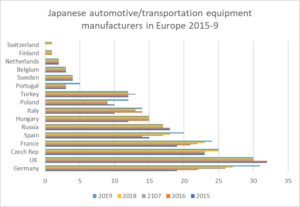

The decline in numbers of Japanese companies in the UK is mainly due to a reduction in Japanese companies in the manufacturing and financial sectors. There has also been a drop in the number employed in automotive manufacturing. On top of this, the main driver of the past few years behind the rising employee and company numbers – big-ticket M&As followed by expansion in employee numbers – has been less of a force more recently.

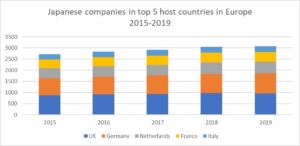

To understand more about the trends in Japanese companies in the UK in terms of investment and employee numbers, how this compares with Germany, France, the Netherlands and Italy and what this might mean for the UK in future years, please download our report below:

Japanese companies in the UK

Send download link to:

For more content like this, subscribe to the free Rudlin Consulting Newsletter. 最新の在欧日系企業の状況については無料の月刊Rudlin Consulting ニューズレターにご登録ください。

Read More

Within Europe, the number of people employed by Japanese companies rose 18% from 2015 to 2019. Those countries where the number of Japanese company employees has fallen are countries where there has been a rise in populism, civic unrest and political risk. UK employee numbers fell 9% 2018-9 (the first decline since at least 2015), Spanish employee numbers fell 19% 2018-9, Hungary’s fell 18%, Turkey’s 10%, Poland and Italy also showed small decreases in employee numbers.

Within Europe, the number of people employed by Japanese companies rose 18% from 2015 to 2019. Those countries where the number of Japanese company employees has fallen are countries where there has been a rise in populism, civic unrest and political risk. UK employee numbers fell 9% 2018-9 (the first decline since at least 2015), Spanish employee numbers fell 19% 2018-9, Hungary’s fell 18%, Turkey’s 10%, Poland and Italy also showed small decreases in employee numbers. The number of Japanese companies in the UK has fallen by 1% 2018-9, from 972 to 966, the first drop since at least 2015, having risen 11% 2015-2018. France also saw a 2% drop in the number of Japanese companies, even though employee numbers are up. Germany attracted a 4% increase in Japanese companies from 2018-9, having risen 13% 2015-8. Netherlands had a 1% increase 2018-9 (13.5% 2015-8) and Italy had a 2% rise in Japanese companies 2018-9, and an increase of 11.8% 2015-8.

The number of Japanese companies in the UK has fallen by 1% 2018-9, from 972 to 966, the first drop since at least 2015, having risen 11% 2015-2018. France also saw a 2% drop in the number of Japanese companies, even though employee numbers are up. Germany attracted a 4% increase in Japanese companies from 2018-9, having risen 13% 2015-8. Netherlands had a 1% increase 2018-9 (13.5% 2015-8) and Italy had a 2% rise in Japanese companies 2018-9, and an increase of 11.8% 2015-8.