Brexit watch – Top 30 Japanese companies in the UK

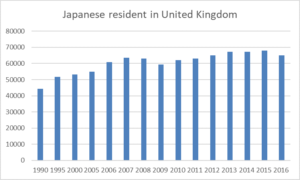

We’ve been tracking the 30 biggest Japanese employers in the UK for over 3 years now, so it seems a good moment as Brexit draws nearer to see what changes they have made over the past three years, explicitly or implicitly, to prepare for Brexit and beyond. Overall, the top 30 Japanese companies in the UK have had a good 3 years’ in the UK, with total number employed increasing by nearly 15% to just under 90,000, out of the 140,000 employed by 1000 Japanese companies that is usually cited. I even wonder whether that 140,000 ought to be revised substantially upwards, as I believe the estimate dates from 2015.

However the average increase conceals some hefty drops (Fujitsu, Nomura and Yazaki) and substantial increases – the latter largely due to acquisitions.

Nearly every annual report from the companies that make up the 30 biggest Japanese employers mentions Brexit, but few state explicitly what actions they have taken to deal with the risk, unless they are financial services companies facing regulatory issues. Most note that the outcome is uncertain, and that they are monitoring and planning.

No tax haven please we’re Japanese

As well as Brexit, another factor that some Japanese companies in the UK have to take into account is the tightening of the Japanese tax haven law. Passive income such as dividends and royalties, if received in a country with a corporate tax below 20%, will be subject to charges from the Japanese tax authorities. The UK corporation tax rate is 19%, due to go down in stages to 17% and Theresa May has recently promised “whatever your business, investing in a post-Brexit Britain will give you the lowest rate of corporation tax in the G20.”

As I stated in my speech to the UK Tax Forum, because of their long term, stakeholder oriented, risk averse ethos, Japanese companies are not really interested in the UK as a tax haven. Panasonic, seen as a bellwether in terms of corporate governance in Japan, cited the tax law as the reason to move its headquarter function from the UK to the Netherlands, where the headline rate of corporate tax is 25% (although sweetheart deals can be done). I also think that the decision of the European headquarters in the UK of trading companies Sumitomo Corporation and Mitsubishi Corporation to sell their shares in investments such as Princes and Triland Metals in the UK to their Japan headquarters is part of this drive – to avoid being seen as using the UK as a tax haven for their dividend earnings.

Whose standards are they anyway?

Japanese companies would be more interested in the second part of May’s statement – “you will access service industries and a financial center in London that are the envy of the world, the best universities, strong institutions, a sound approach to public finance and a consistent and dependable approach to high standards but intelligent regulation”.

But of course the question they will be asking is “whose high standards?”

There are around 200 Japanese companies with manufacturing in the UK, and we estimate around 50% of their production on average goes to the EU (excluding the UK). 30% is to the UK and the remainder to the rest of the world. In Toyota’s case, over 80% of their production in the UK is exported to the EU. So it’s no surprise that, as repeatedly stated, including in the Japanese Ministry of Finance’s “Message to the UK and the EU” of a couple of years’ ago, Japanese business want harmonised regulations and standards across the UK and the EU.

All the Japanese financial services companies affected by EU regulation have taken action – Hitachi Capital and MUFG have strengthened or set up bases in Amsterdam, MS&AD in Brussels, Sompo International in Luxembourg, SMFG, Mizuho and Nomura in Frankfurt.

The rise of the pure UK plays

Looking at who’s in and who’s out of the Top 30, the rise of “pure services” is noticeable, largely through acquisitions such as MS&AD acquiring Lloyds underwriters Amlin and InsureTheBox, Dentsu acquiring multiple advertising and marketing agencies in the UK, Outsourcing acquiring recruitment agencies and government debt collectors. Bubbling under are Park24, now the owner of National Car Parks. Many of these investments are very domestic UK market oriented, so Brexit proof in the sense that they are not reliant on the European single market in terms of supply chains, regulation or freedom of movement.

Conversely manufacturing companies have dropped out – such as JTI, with the closure of its Gallaher factory in Northern Ireland last year and Fujifilm, who have three different production sites in the UK.

Freedom of movement and solutions

As well as emphasising the need to harmonise regulations and standards, and ensure tariff free trade, the Japanese government “Message to the UK and the EU” of two years ago also pointed out that Japanese companies in all sectors employ large numbers of non-British EU nationals in the UK. Because many of them have UK -based regional headquarters, or have design and engineering or customer support centres in the UK, they rely on the freedom of movement of these non-British EU nationals as well as the freedom of movement of British employees themselves, to visit or be seconded to client sites to provide pre sales, installation and aftercare support. This also applies to Japanese engineers visiting the UK from Japan who at the moment are finding themselves being turned away because they gave the wrong answer at the border, saying they have come to the UK “to work”.

This last issue is likely to be raised quite insistently in any post Brexit trade deal between Japan and the UK, and if not solved, I would expect to see the numbers employed by the Top 30 in the UK to fall in the years to come.

FREE PDF DOWNLOAD OF TOP 30 JAPANESE EMPLOYERS IN THE UK 2021

For more content like this, subscribe to the free Rudlin Consulting Newsletter. 最新の在欧日系企業の状況については無料の月刊Rudlin Consulting ニューズレターにご登録ください。

Read More

On the face of it, it looks to have been a good couple of years’ for

On the face of it, it looks to have been a good couple of years’ for

The report on Sky News about the

The report on Sky News about the