Koyo Bearings Europe changes name to JTEKT Automotive England

Koyo Bearings Europe in the UK has changed its name to JTEKT Automotive England. It decided in 2021/2 to stop serving European market and transfer some production to continental Europe. UK employees at Koyo Bearings Europe have fallen to 205 from 279 in 2016. Koyo UK has become JTEKT Sales UK and has 20 employees.

JTEKT ‘s European headquarters is in the Netherlands, coordinating 28 subsidiaries across the region, employing 6,699 people in 2022 – of whom 365 are in the UK, across 4 subsidiaries.

Koyo was the bearings brand name of JTEKT since Toyoda Machine Works and Koyo Seiko merged in 2006 to form JTEKT. Now all businesses and brands are being rebranded to JTEKT globally.

For more content like this, subscribe to the free Rudlin Consulting Newsletter. 最新の在欧日系企業の状況については無料の月刊Rudlin Consulting ニューズレターにご登録ください。

Read More

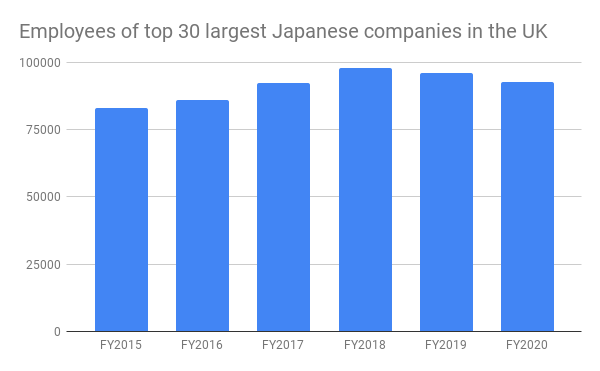

The total number of UK employees of the top 30 Japanese company groups fell 2.6% from 2019/20 to 2020/2021 – a strengthening of the downward trend in employee numbers since 2018/9. The peak of employment by the 30 largest Japanese company groupings in the UK was 97,827 in 2018/9 and this has now fallen by 5,000 to 92,851 employees. The top 30 represent around two thirds of the 137,000 people employed by 1,200+ Japanese companies in the UK.

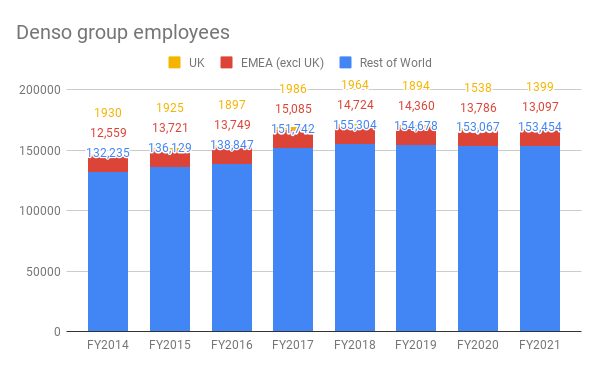

The total number of UK employees of the top 30 Japanese company groups fell 2.6% from 2019/20 to 2020/2021 – a strengthening of the downward trend in employee numbers since 2018/9. The peak of employment by the 30 largest Japanese company groupings in the UK was 97,827 in 2018/9 and this has now fallen by 5,000 to 92,851 employees. The top 30 represent around two thirds of the 137,000 people employed by 1,200+ Japanese companies in the UK. Konica Minolta acquired various UK companies before Brexit, but since Brexit has shrunk down and consolidated its operations in the UK and is focusing more on their European HQ in Germany and also the Czech Republic. The longer term trend of shifting away from manufacturing in the UK, to manufacturing elsewhere in Europe is seen at Denso, the Toyota group automotive parts manufacturer – UK employee numbers peaked in FY2018, and have been falling since, and are now 27.5% below the FY2014 level, whereas employment in the rest of the region is up 4.3% and global employee numbers, excluding UK, have risen 16% since FY2014.

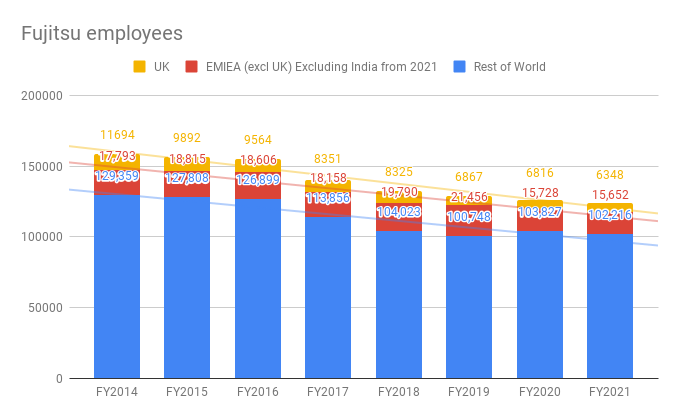

Konica Minolta acquired various UK companies before Brexit, but since Brexit has shrunk down and consolidated its operations in the UK and is focusing more on their European HQ in Germany and also the Czech Republic. The longer term trend of shifting away from manufacturing in the UK, to manufacturing elsewhere in Europe is seen at Denso, the Toyota group automotive parts manufacturer – UK employee numbers peaked in FY2018, and have been falling since, and are now 27.5% below the FY2014 level, whereas employment in the rest of the region is up 4.3% and global employee numbers, excluding UK, have risen 16% since FY2014. Five years’ ago, Fujitsu was the largest Japanese corporate group in the UK, with 9,892 people. It has lost 3,000 employees since, and was the fourth largest Japanese group in the UK in FY2020. As of FY2021, Fujitsu has 6,348 employees in the UK, 45% down on FY2016, compared to a 21% decrease globally, excluding the UK. Growth at Fujitsu has been in India (and Fujitsu’s CTO is Indian) and in its global delivery centres in countries such as Poland and the Philippines.

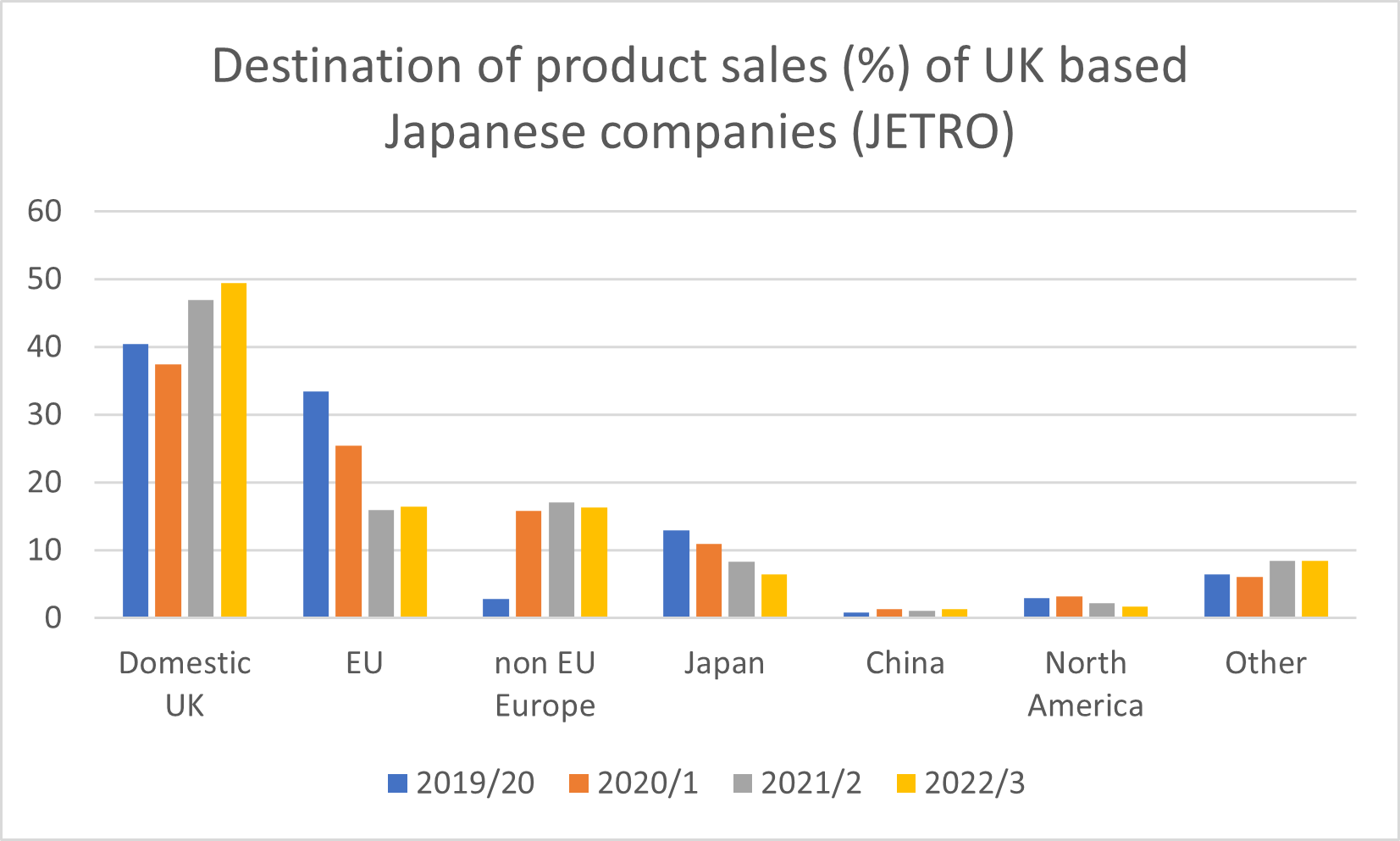

Five years’ ago, Fujitsu was the largest Japanese corporate group in the UK, with 9,892 people. It has lost 3,000 employees since, and was the fourth largest Japanese group in the UK in FY2020. As of FY2021, Fujitsu has 6,348 employees in the UK, 45% down on FY2016, compared to a 21% decrease globally, excluding the UK. Growth at Fujitsu has been in India (and Fujitsu’s CTO is Indian) and in its global delivery centres in countries such as Poland and the Philippines. Japanese companies in the UK are showing an increasing focus on the UK domestic market for their sales, with an average of 49.4% of sales to the UK market, 2.4% up on 2021/2, compared to a European average of domestic sales of 37.7%. UK companies are selling on average 16.5% of sales to EU countries, compared to 37.6% of sales to other EU countries (excluding their own country) for Japanese companies located in the EU. Unsurprisingly, Japanese companies in the UK have become more UK oriented since Brexit, as many of the EU sales and coordination functions have shifted from the UK to the EU – and is now potentially stabilising after the sharp decline over 2019/20 to 2021/2

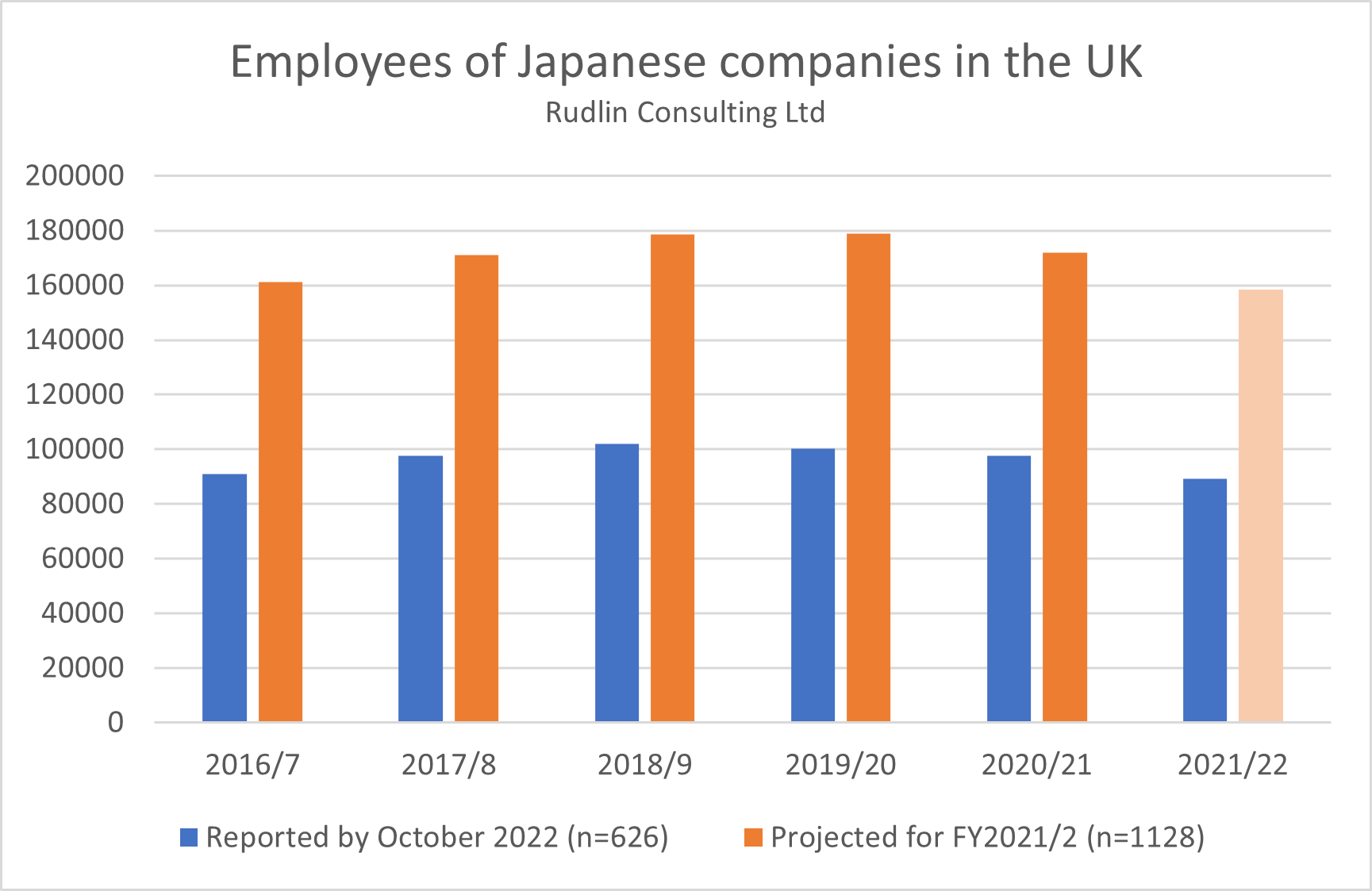

Japanese companies in the UK are showing an increasing focus on the UK domestic market for their sales, with an average of 49.4% of sales to the UK market, 2.4% up on 2021/2, compared to a European average of domestic sales of 37.7%. UK companies are selling on average 16.5% of sales to EU countries, compared to 37.6% of sales to other EU countries (excluding their own country) for Japanese companies located in the EU. Unsurprisingly, Japanese companies in the UK have become more UK oriented since Brexit, as many of the EU sales and coordination functions have shifted from the UK to the EU – and is now potentially stabilising after the sharp decline over 2019/20 to 2021/2 Overall, the total number employed by those Japanese companies in the UK who have reported their results has fallen by 8% over the past year. This is an acceleration of a decline which started three years ago – employee numbers had fallen 3% the previous year, and 2% the year before that. This was preceded by a couple of years of growth from 2016/7 to 2018/9. Projected, this suggests that the number of people employed by Japanese companies in the UK will fall to 158,000 by the end of the financial year 2021/2, below the 161,000 that were employed by Japanese companies in 2016/7 and a 14,000 drop on the numbers employed in 2020/1.

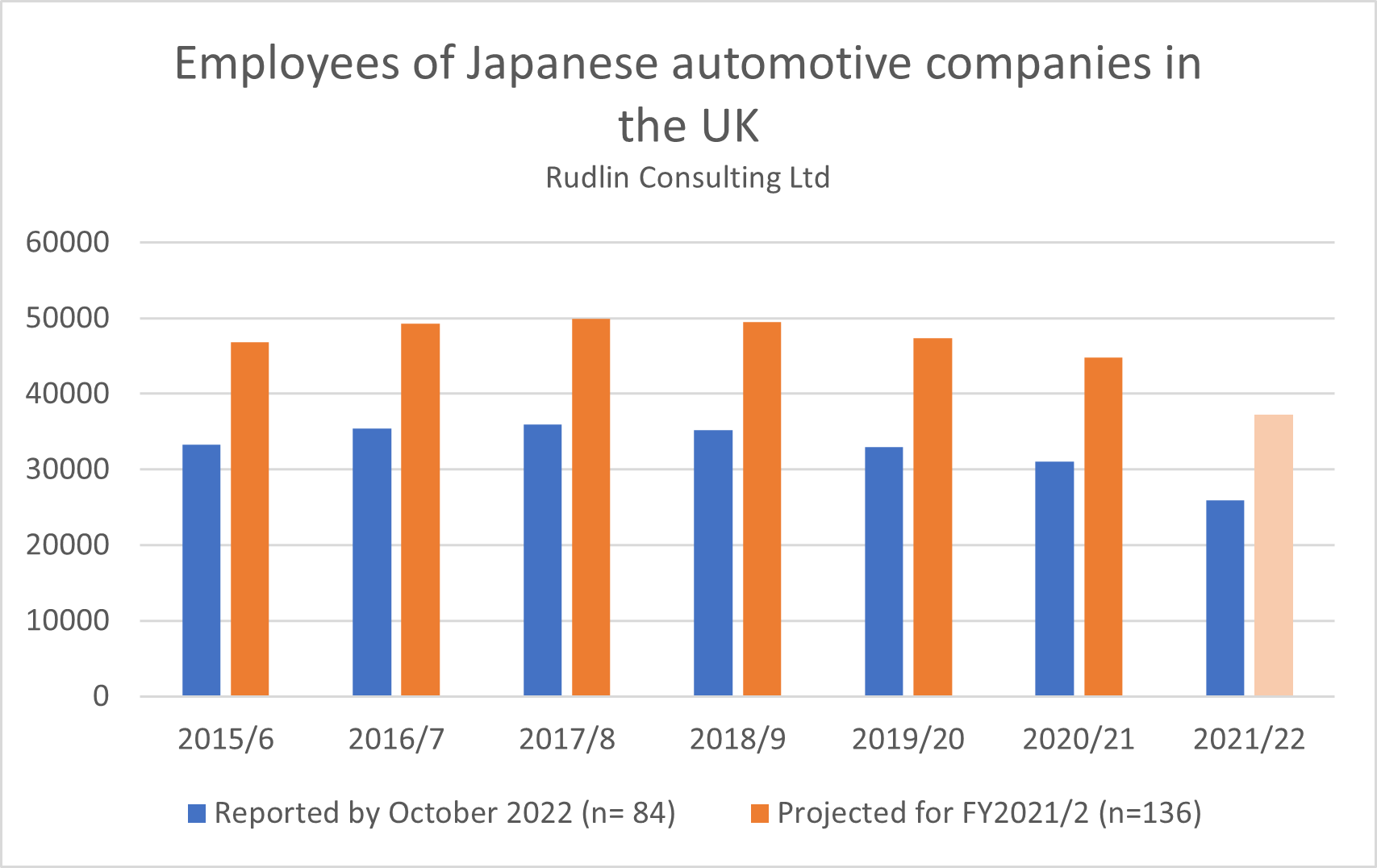

Overall, the total number employed by those Japanese companies in the UK who have reported their results has fallen by 8% over the past year. This is an acceleration of a decline which started three years ago – employee numbers had fallen 3% the previous year, and 2% the year before that. This was preceded by a couple of years of growth from 2016/7 to 2018/9. Projected, this suggests that the number of people employed by Japanese companies in the UK will fall to 158,000 by the end of the financial year 2021/2, below the 161,000 that were employed by Japanese companies in 2016/7 and a 14,000 drop on the numbers employed in 2020/1. It is certainly partly due to the impact of Honda closing its Swindon factory in July 2021. That meant the loss of nearly 3,000 jobs and it looks likely a further 5,000 jobs will have been lost in the automotive sector over the past year – many of which were dependent on Honda. The decline in employment in the automotive sector began in 2018/9, a year or two before other sectors began to lose jobs.

It is certainly partly due to the impact of Honda closing its Swindon factory in July 2021. That meant the loss of nearly 3,000 jobs and it looks likely a further 5,000 jobs will have been lost in the automotive sector over the past year – many of which were dependent on Honda. The decline in employment in the automotive sector began in 2018/9, a year or two before other sectors began to lose jobs.