Japanese financial services companies in the UK

These two pieces of research from Dr Sarah Hall (a professor of economic geography at the University of Nottingham and Fellow of UK in a Changing Europe) and Martin Heneghan confirm what we have seen in our own researches on Japanese financial services companies in the UK. There has not been as drastic a decline in numbers employed by Japanese companies in the sector as expected since Brexit, instead, it has been more of a slight increase, followed by flatlining.

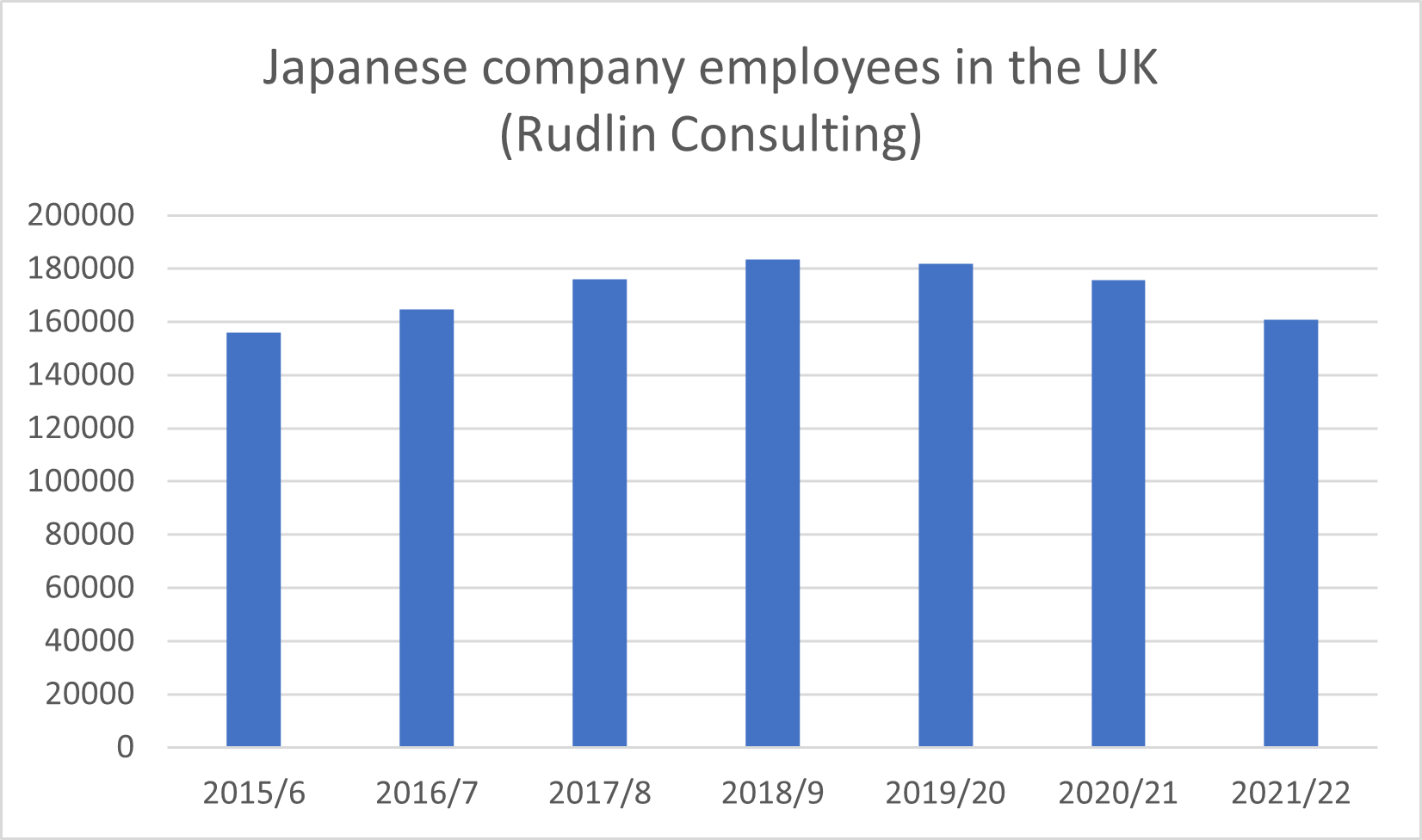

We estimate the numbers employed in the UK by Japanese financial services companies was around 13,400 in 2015/6, rising by around 1,000 to 2019/20, dropping slightly in 2020/21 and then returning to 2019/20 levels the year after. It is hard to be precise about the absolute numbers and trend, as two of the three Japanese megabanks, who employ around 1,000 people each, are branches of their Japan headquarters, so do not issue annual reports in which employee numbers are reported. These two megabanks, Mizuho and MUFG, may come under pressure from the Bank of England to have subsidiaries in the UK too, according to recent rumours.

We estimate there are around 160,000 people employed by Japanese companies in all sectors, so the financial services sector represents less than 10% of this. As of June 2022, 1.06 million people were employed in the UK in the financial services sector in the UK, so Japanese owned companies only represent 1.3% of the total employed in the sector.

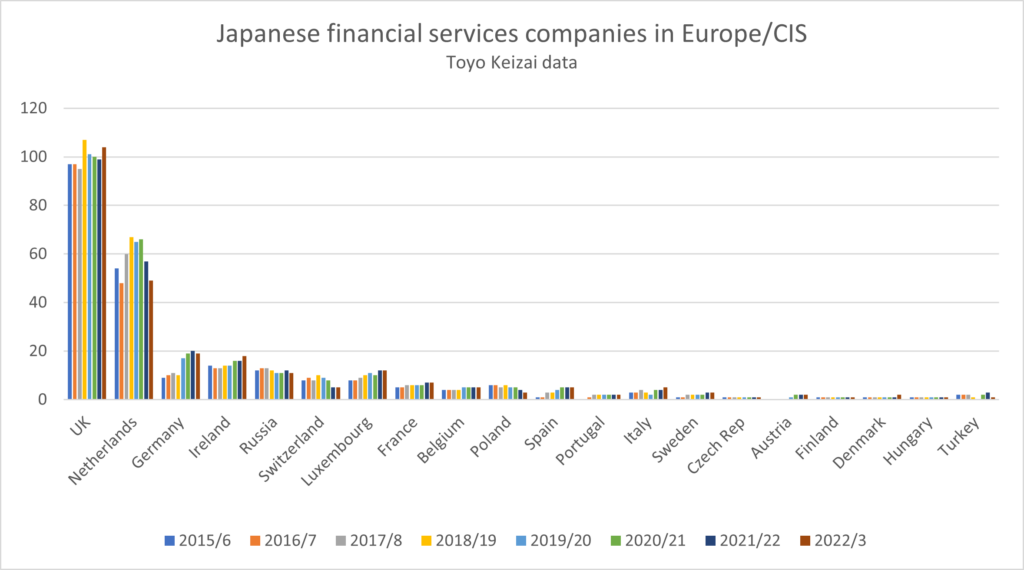

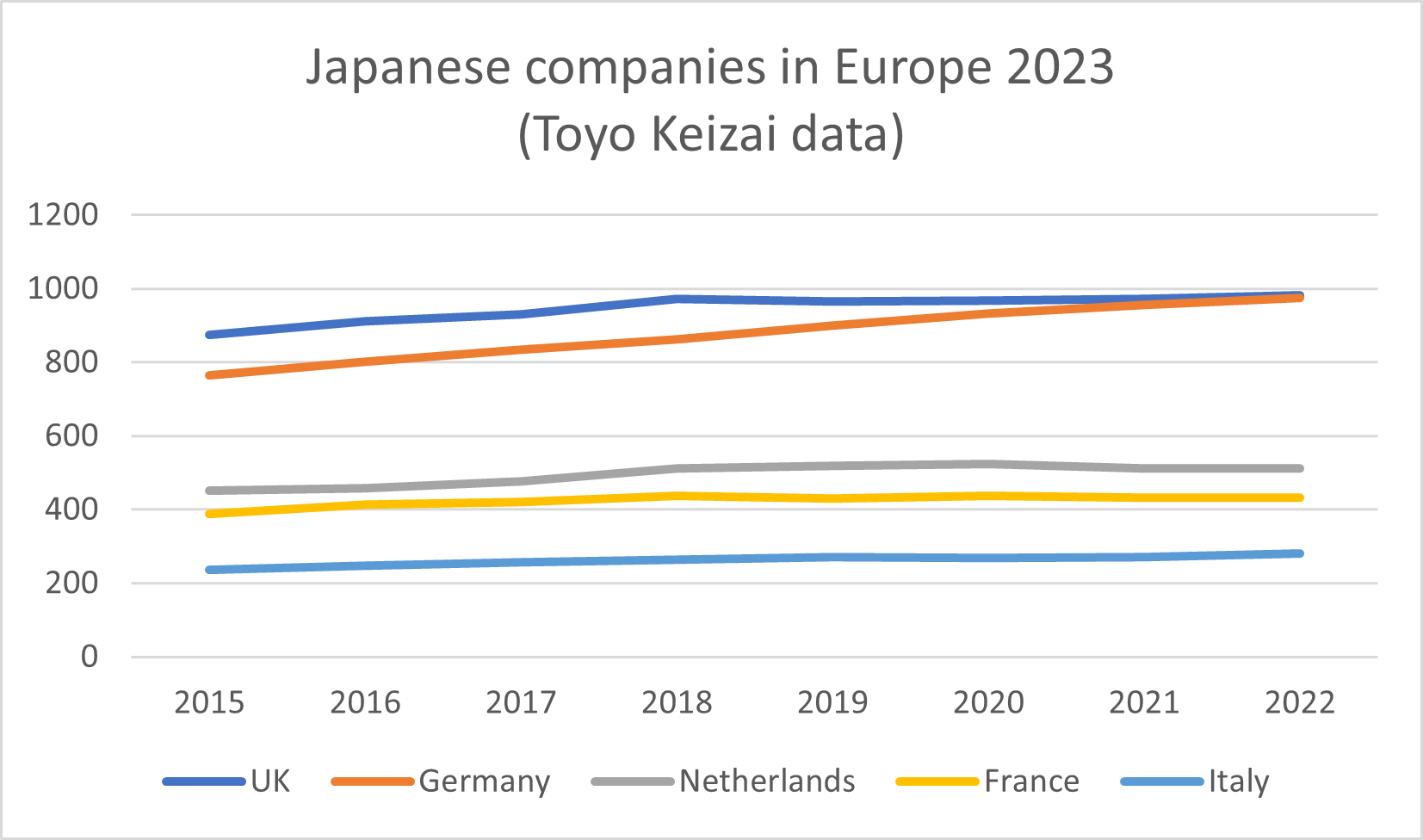

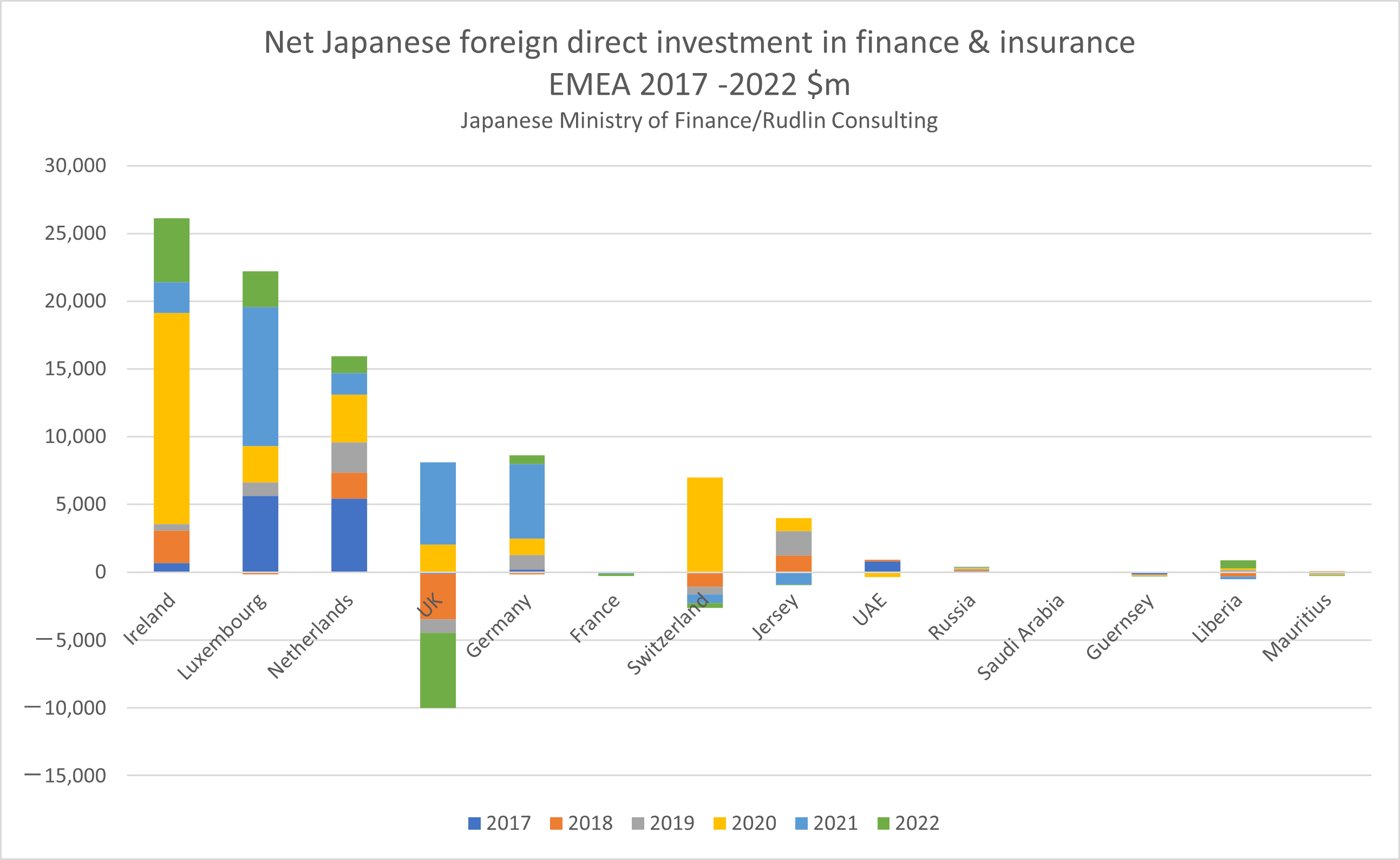

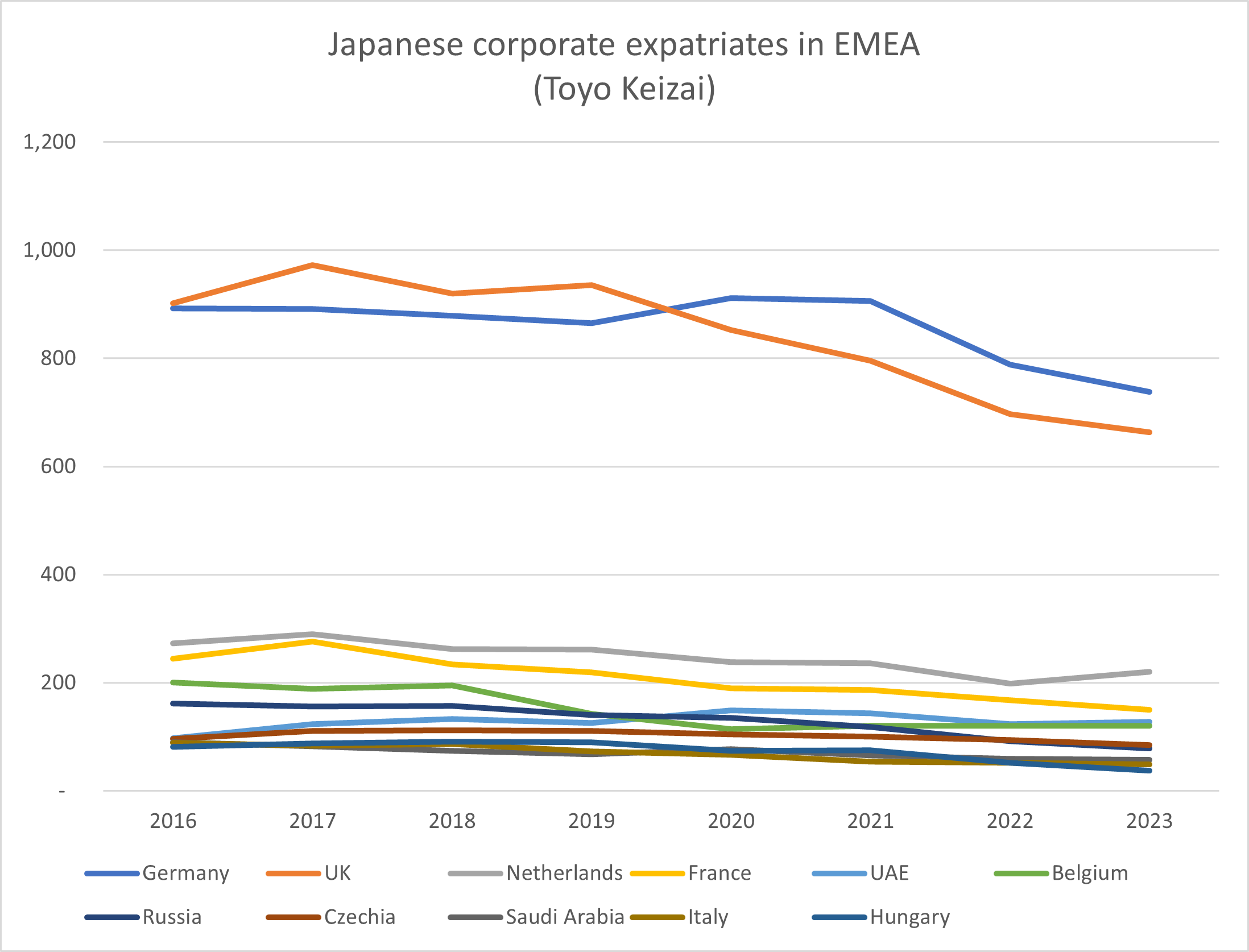

The other issue raised by the two pieces of research are whether other EU cities have benefited from any additional growth, which the UK has missed out on. As can be seen from the chart, Toyo Keizai data shows that there was an overall upward trend in the number of Japanese financial services companies in the European region, of around 12% from 2015/6 to 2022/23. The UK still dominates as a host, and the numbers of companies hosted rose 7% – so below trend. Germany doubled the number of Japanese financial services companies it hosted over the period. The numbers rose sharply in the Netherlands and then dropped. Just as Dr Hall’s research suggests, Ireland, Luxembourg and France seem to have benefited, albeit from a much smaller base.

The other issue raised by the two pieces of research are whether other EU cities have benefited from any additional growth, which the UK has missed out on. As can be seen from the chart, Toyo Keizai data shows that there was an overall upward trend in the number of Japanese financial services companies in the European region, of around 12% from 2015/6 to 2022/23. The UK still dominates as a host, and the numbers of companies hosted rose 7% – so below trend. Germany doubled the number of Japanese financial services companies it hosted over the period. The numbers rose sharply in the Netherlands and then dropped. Just as Dr Hall’s research suggests, Ireland, Luxembourg and France seem to have benefited, albeit from a much smaller base.

Toyo Keizai breaks down the sector into banks, trust banking, securities, investment trusts and advisory, commodities, lending and credit, leasing and investment businesses, as well as life and non life insurance and “other” finance. “Other” finance is the sector which showed the most growth for the UK – perhaps fintech and less traditional financial services are included in this. For Ireland the leasing sector, particularly aircraft leasing, is a growth area. Germany now hosts four Japanese securities companies, from none in 2015/6. The growth and then decline for the Netherlands seems to have been mostly in investment businesses. Luxembourg has gained one or two companies across all sectors.

Given that the rather nebulous “investment businesses” and “other finance” are the two biggest sectors, showing the most growth along with leasing, we agree with Dr Hall’s conclusion that “given the complex interplay of these two factors, we suggest that far from being done, Brexit is being played out within a sector that is itself in a period of profound flux and hence it is likely to be some time before the full impacts of Brexit of UK financial services, and their consequences for wider economic growth, are fully understood.”

Our list of the 94 Japanese financial services companies in the UK, giving their full name, city or town of location, number employed, description of financial services offered and ultimate parent company is available for £10+VAT. Please email us for an invoice.

For more content like this, subscribe to the free Rudlin Consulting Newsletter. 最新の在欧日系企業の状況については無料の月刊Rudlin Consulting ニューズレターにご登録ください。

Read More LinkedIn

LinkedIn YouTube

YouTube

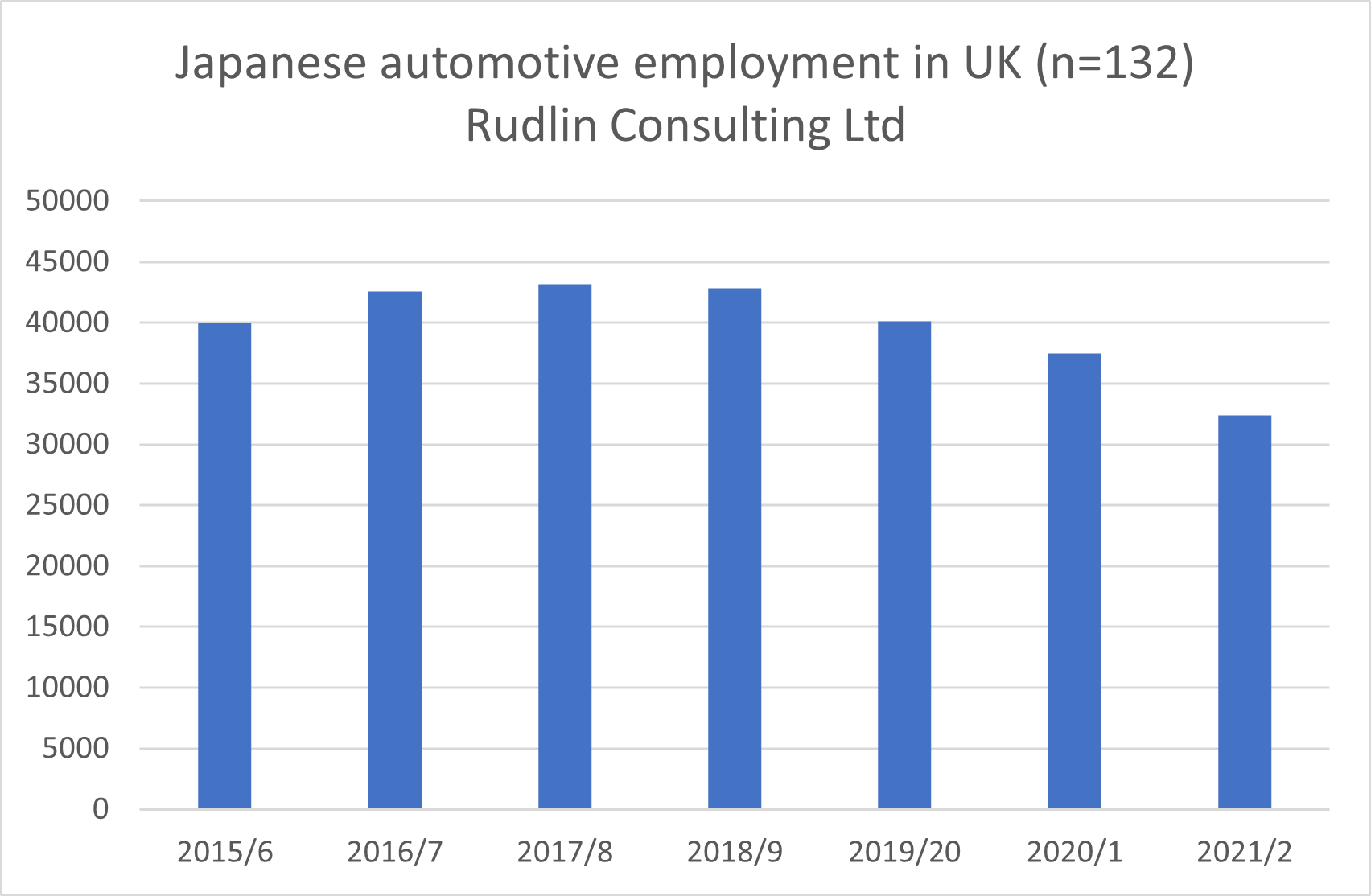

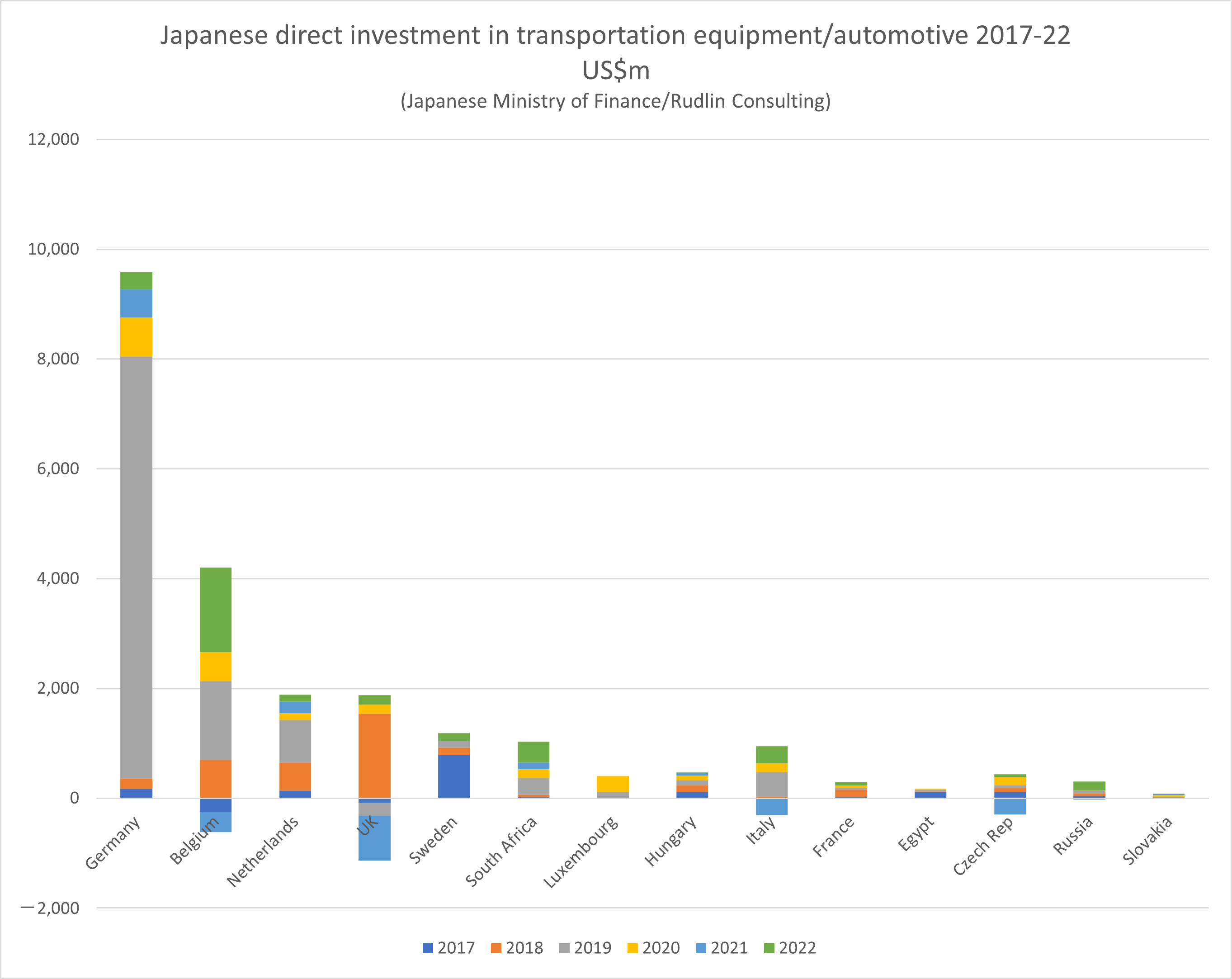

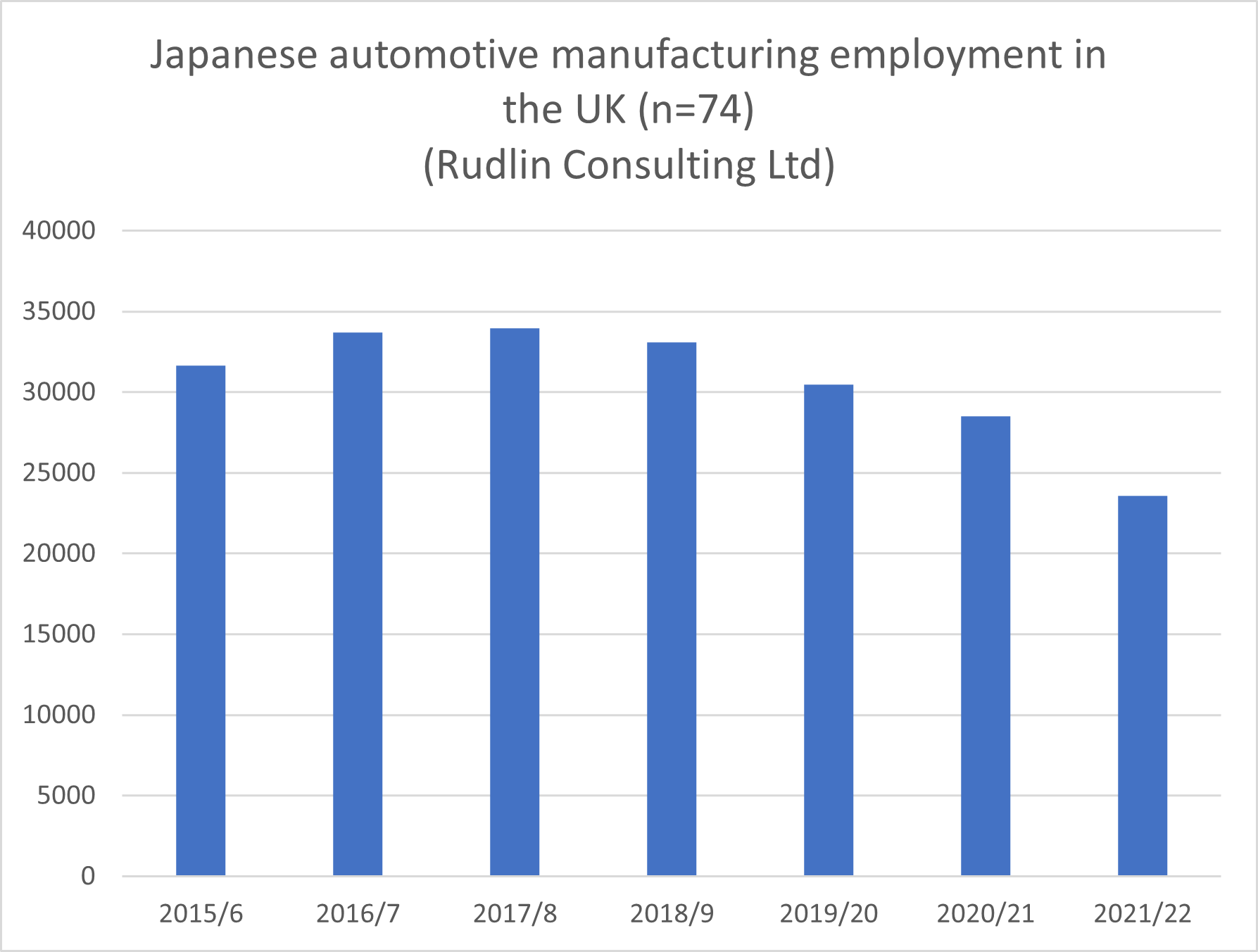

If we just focus on Japanese companies with production in the UK, there was a 26% decline in employment over 2018-2022 – unsurprisingly close to the overall trend – as around 74% of all Japanese automotive employees in the UK are employed in manufacturing operations.

If we just focus on Japanese companies with production in the UK, there was a 26% decline in employment over 2018-2022 – unsurprisingly close to the overall trend – as around 74% of all Japanese automotive employees in the UK are employed in manufacturing operations.