The energy crisis

With warnings of train strikes in the summer and power cuts in the winter, and rising inflation, it really does feel like Britain has returned to the 1970s. I was a little girl, living in Japan, during most of the 1970s, but was still in Britain for a year or so when the first power cuts happened. I remember being quite excited about having to do everything by candlelight. I doubt the adults were as thrilled, however.

Memories of my childhood in Japan came back to me as I was looking for alternative heating for our house that was not reliant on mains electricity or gas. I discovered that Japanese manufacturers are selling wick type paraffin heaters in Europe, just like the ones I remember from my childhood in Sendai, only less smelly.

I shared this with one of my friends, about the same age as me, and she told me that her family home, in 1970s Britain, was also heated with paraffin heaters. They did not have any central heating, and, she added, the paraffin heaters were used to heat the bathroom on bath night. In those days, it was quite common just to have a bath once a week, often sharing the dirty water with other members of the family.

For many homes then, there was only enough hot water for two bathfuls a day, coming from an immersion tank, which ran on electricity and would often be set to switch on at night, when electricity was cheaper.

Now most British people shower once a day, getting their hot water “on demand” from a combination gas boiler, which also runs the central heating. Even before the threat of power cuts, the government has been considering incentivising households to switch away from gas boilers to air source heat pumps for their central heating and water heating. So far, however, there has not been a big take up.

One of the issues, apart from the high upfront cost of installation, is that planning permission may be required for an outside unit. This also caused difficulties in the uptake of solar panel installation. Many British people live in old houses, or conservation areas, where visible changes to the houses that are not in harmony with the surrounding environment cannot be made.

This may also prove to be an issue with the new home batteries that Japanese companies such as Toyota Motor have been introducing. Because they are also used to charge cars, they need to be outside – which is fine for those who have homes with a parking space incorporated. But many city dwellers park their cars on the road in front of their house, and this means that they have to run a cable out of their front door and across a pavement to charge their cars.

No doubt the energy crisis will eventually provide ingenious answers to this, but this winter I think it might have to be candles and paraffin heaters for many of us.

For more content like this, subscribe to the free Rudlin Consulting Newsletter. 最新の在欧日系企業の状況については無料の月刊Rudlin Consulting ニューズレターにご登録ください。

Read More

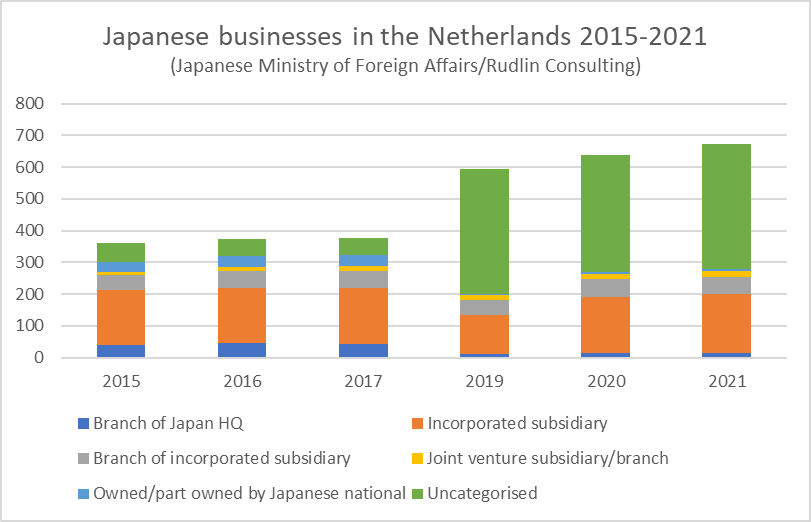

Partly this is due to the large proportion of potentially “brass plate” type Japanese companies, with no employees in the Netherlands – often the regional holding company for a group of companies. Partly it is due to the lack of disclosure – information on companies in the Netherlands does not seem to be as readily available as it is in the UK, where data on

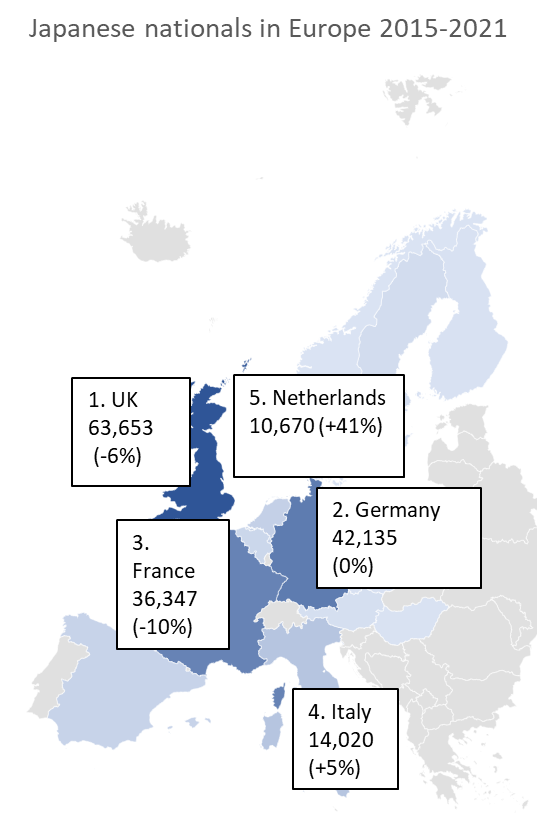

Partly this is due to the large proportion of potentially “brass plate” type Japanese companies, with no employees in the Netherlands – often the regional holding company for a group of companies. Partly it is due to the lack of disclosure – information on companies in the Netherlands does not seem to be as readily available as it is in the UK, where data on  potential customers or employers, it is important to understand this, as the regional headquarters tend to be where the decision makers, big budgets and the most interesting career paths will be based. The number of Japanese expatriates in the country is also an indication of where the decision making influencers are. Although the Netherlands is only the 5th largest host of Japanese nationals in Europe, after the UK, Germany, France and Italy, this number has grown 41% since 2015.

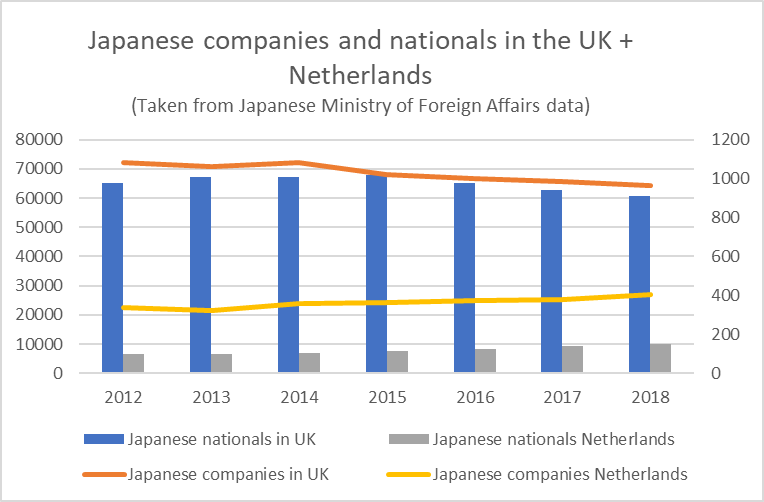

potential customers or employers, it is important to understand this, as the regional headquarters tend to be where the decision makers, big budgets and the most interesting career paths will be based. The number of Japanese expatriates in the country is also an indication of where the decision making influencers are. Although the Netherlands is only the 5th largest host of Japanese nationals in Europe, after the UK, Germany, France and Italy, this number has grown 41% since 2015. The companies we have identified employ around 48,000 people, a 29% increase on 2017/8 – the vast majority (39,000) of whom work for the Top 30 employers in the Netherlands. Japanese companies in the UK, by comparison, employ around 170-180,000 people, and there has been a slight decline in numbers over the past 5 years.

The companies we have identified employ around 48,000 people, a 29% increase on 2017/8 – the vast majority (39,000) of whom work for the Top 30 employers in the Netherlands. Japanese companies in the UK, by comparison, employ around 170-180,000 people, and there has been a slight decline in numbers over the past 5 years.

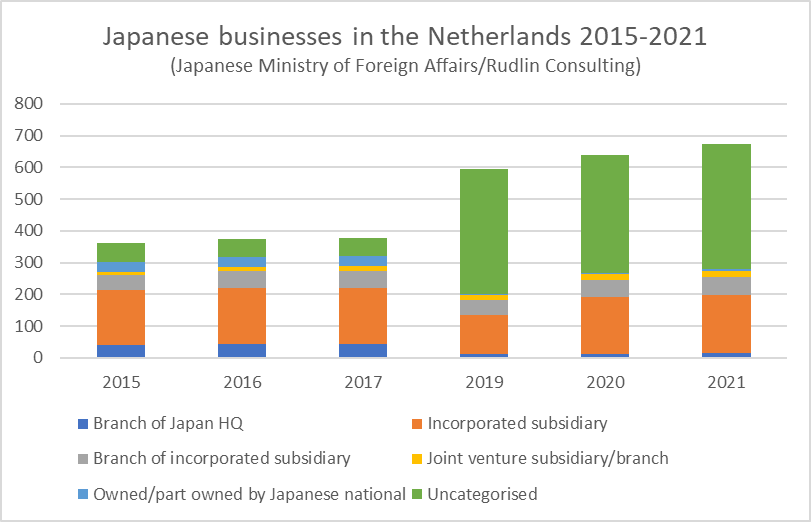

As for the Netherlands, there has been a quintupling of the number of business classified as “uncategorised” from 61 in 2015 to 393 in 2021. These may be brass plate type holding companies. All other categories (incorporated subsidiaries, branches of regional subsidiaries and joint ventures/investments) have increased as well, apart from branches of Japan HQ (which may have now become subsidiaries) and those started by Japanese nationals in the Netherlands. There was an overall rise of 86% of Japanese businesses in the Netherlands since 2015.

As for the Netherlands, there has been a quintupling of the number of business classified as “uncategorised” from 61 in 2015 to 393 in 2021. These may be brass plate type holding companies. All other categories (incorporated subsidiaries, branches of regional subsidiaries and joint ventures/investments) have increased as well, apart from branches of Japan HQ (which may have now become subsidiaries) and those started by Japanese nationals in the Netherlands. There was an overall rise of 86% of Japanese businesses in the Netherlands since 2015.

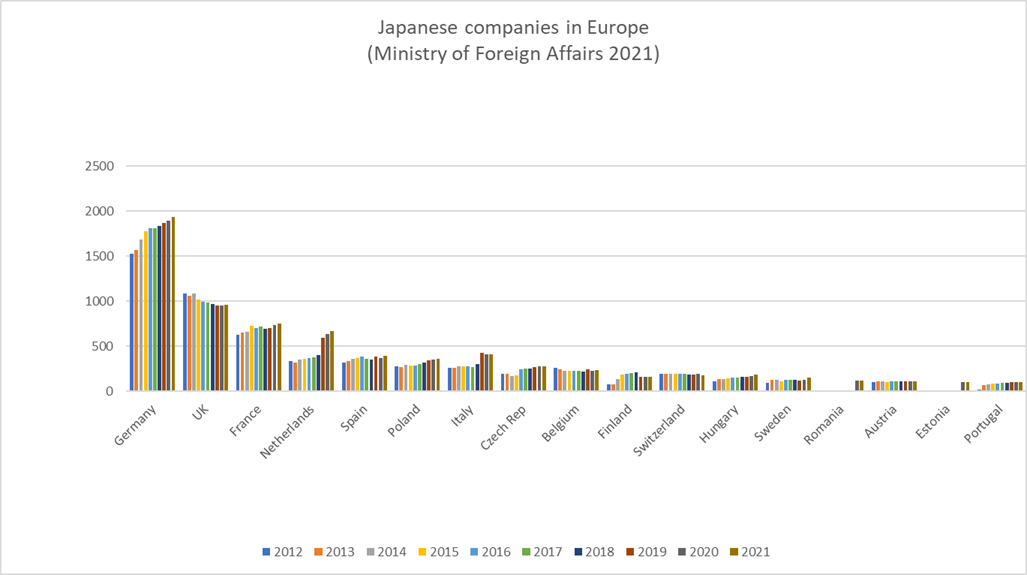

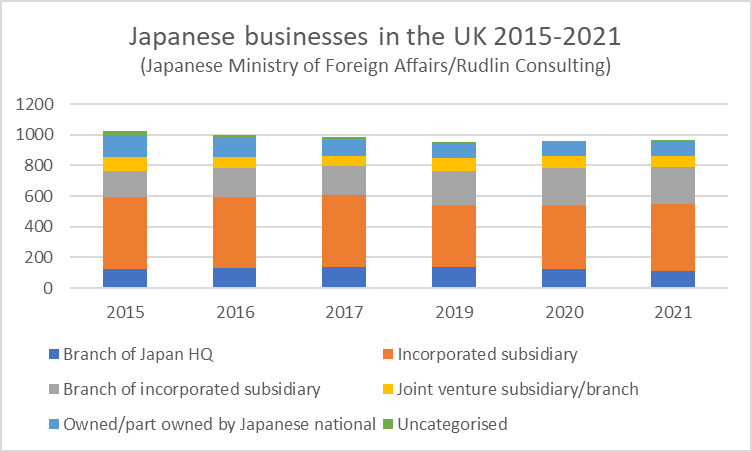

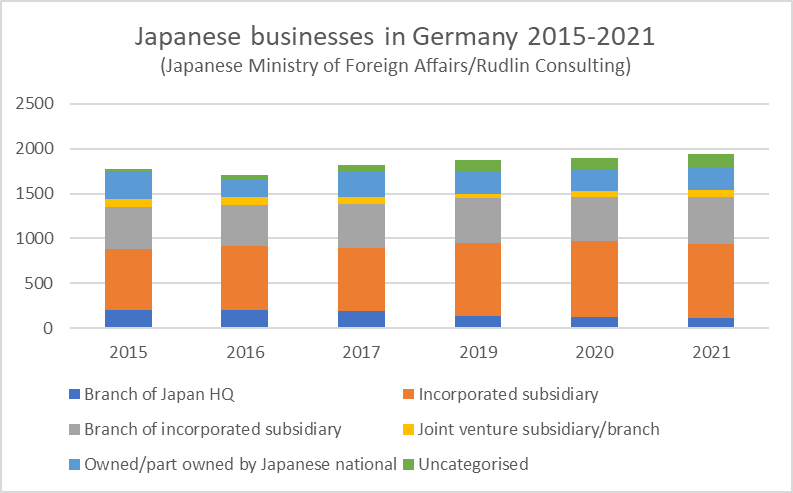

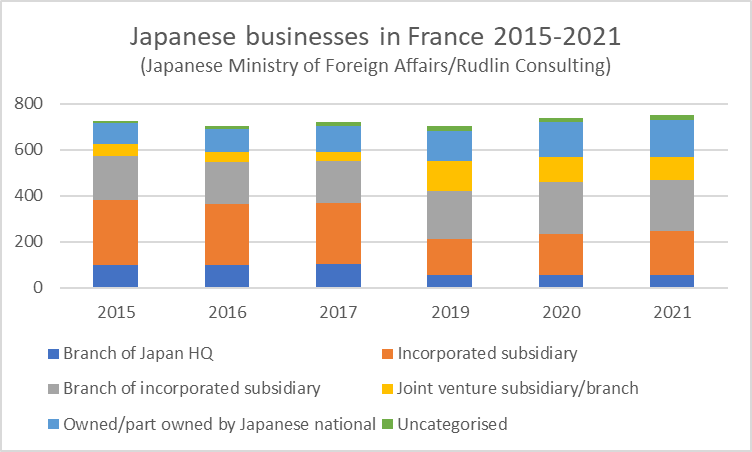

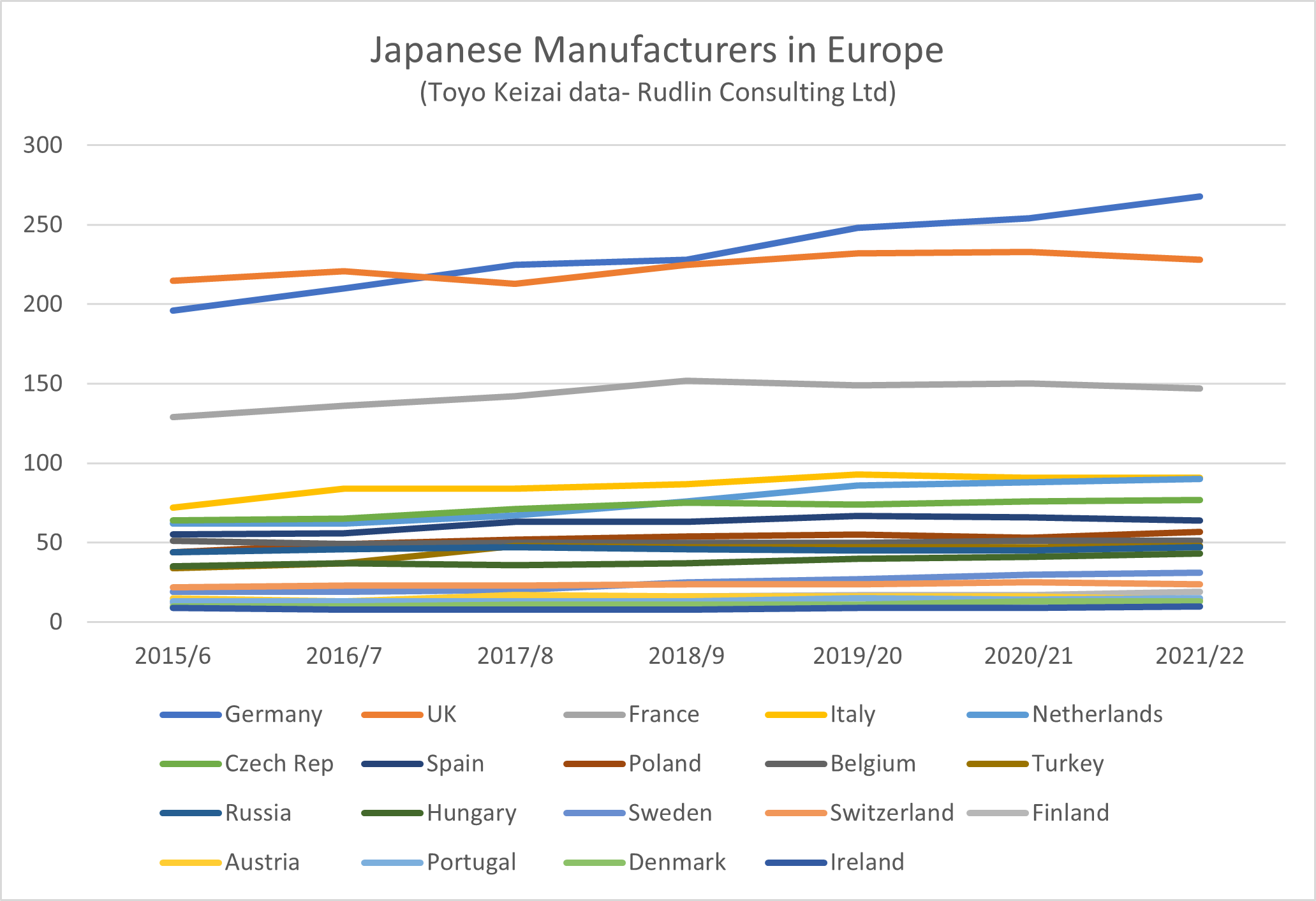

How this compares with other European countries can be seen in the chart on the left – which shows the numbers of all manufacturing companies in Europe, including automotive. According to Toyo Keizai, the number of Japanese manufacturers in the UK dipped around 2017/8, but recovered, with another more recent fall. But there was growth overall since 2015/6, with 228 companies in 2021/2 compared to 215 in 2015/6 – a 6% increase. This is much lower than the overall 20% growth in Europe, and as a consequence the UK is no longer the largest host of Japanese manufacturers.

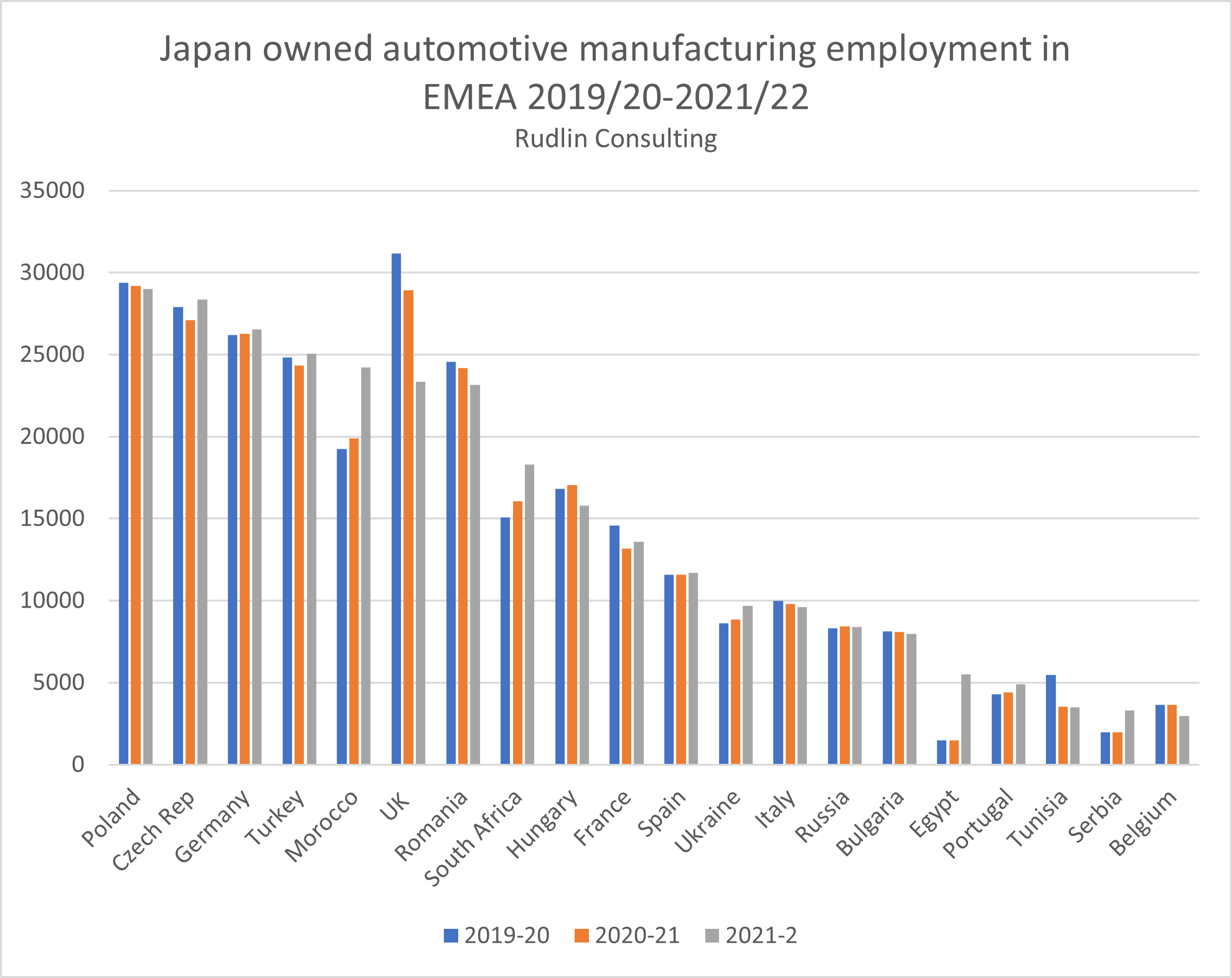

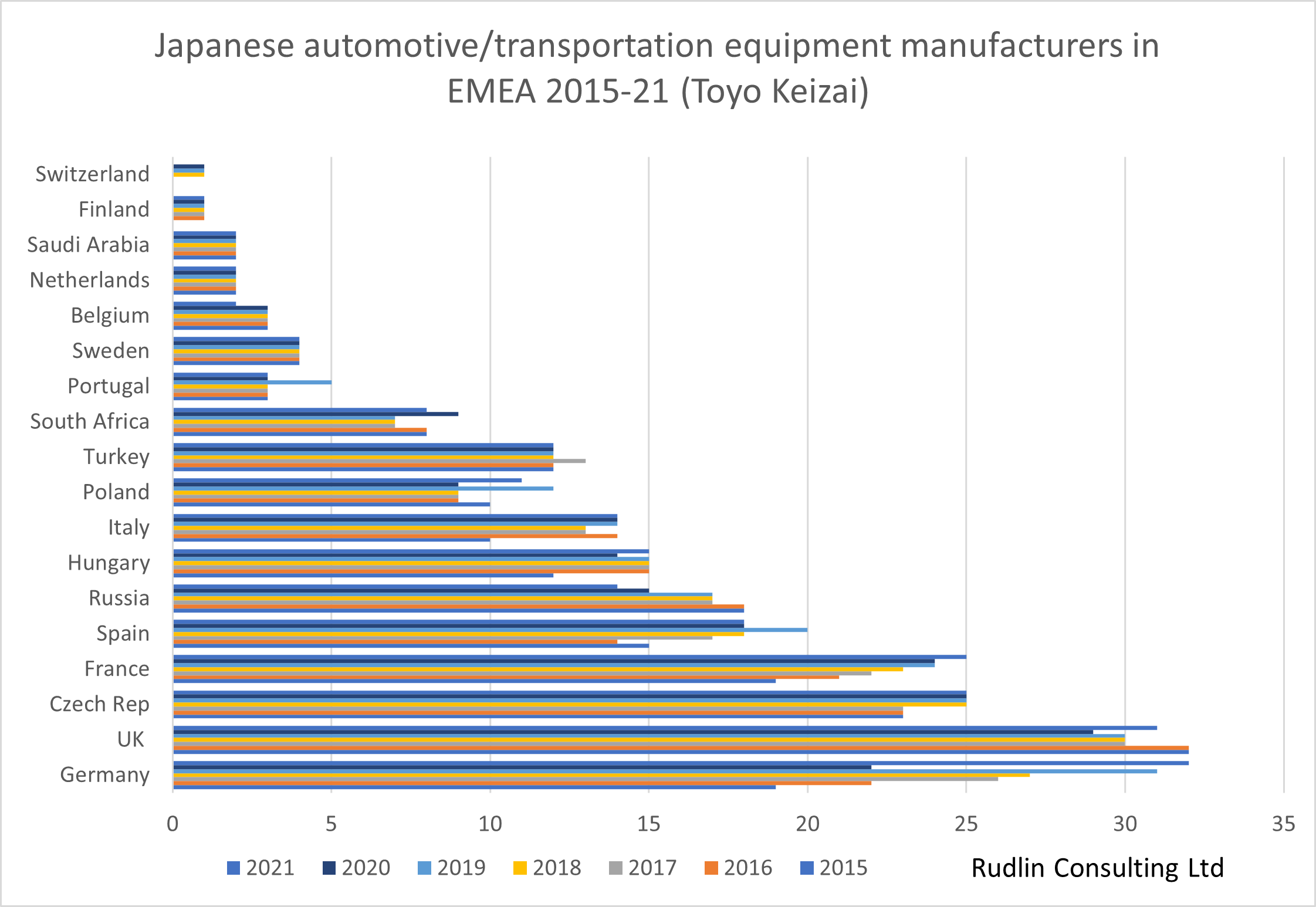

How this compares with other European countries can be seen in the chart on the left – which shows the numbers of all manufacturing companies in Europe, including automotive. According to Toyo Keizai, the number of Japanese manufacturers in the UK dipped around 2017/8, but recovered, with another more recent fall. But there was growth overall since 2015/6, with 228 companies in 2021/2 compared to 215 in 2015/6 – a 6% increase. This is much lower than the overall 20% growth in Europe, and as a consequence the UK is no longer the largest host of Japanese manufacturers. numbers of Japanese automotive manufacturing employees in the EMEA region. According to our estimates, the UK will slip to 6th position in 2021-2022, due to the closure of Honda‘s Swindon plant, along with many of its suppliers shutting down operations. It will be overtaken by Czech Republic, Germany, Turkey and Morocco.

numbers of Japanese automotive manufacturing employees in the EMEA region. According to our estimates, the UK will slip to 6th position in 2021-2022, due to the closure of Honda‘s Swindon plant, along with many of its suppliers shutting down operations. It will be overtaken by Czech Republic, Germany, Turkey and Morocco.

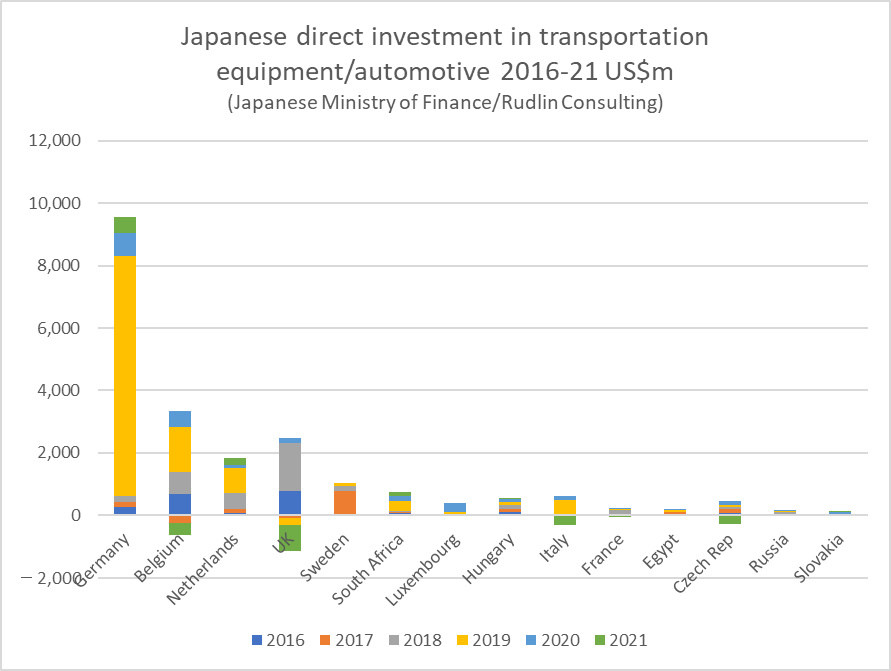

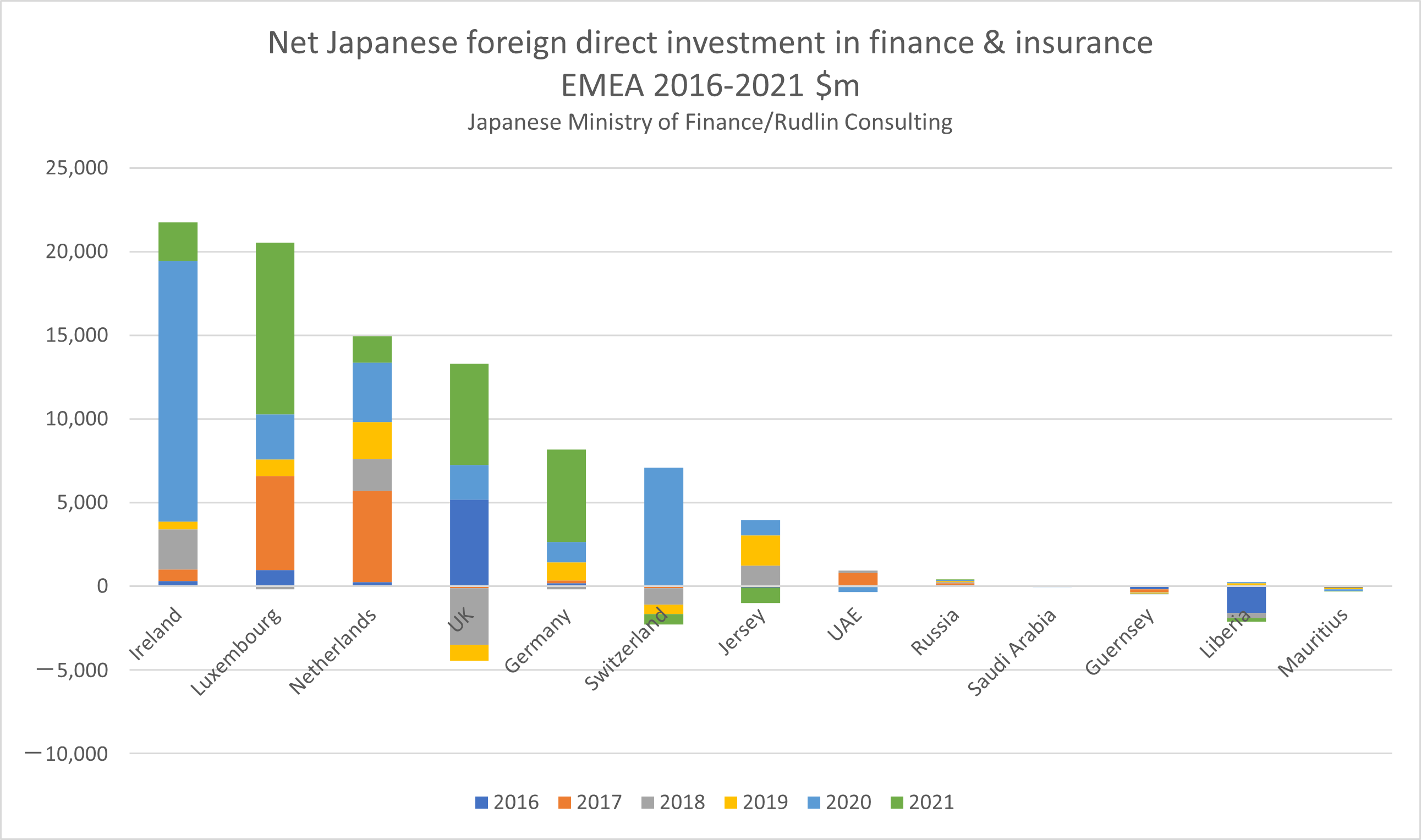

Examining the statistics from Japan’s Ministry of Finance on direct investment flows, it seems the UK benefitted from a big inward investment from Japan into the finance and insurance sector in 2016, then there was net disinvestment in 2017-2019, and then increasing net investment in 2020-21. Conversely, there was little investment into Ireland, Luxembourg or the Netherlands in 2016, but major investments into their finance and insurance sectors in 2017, 2018 and 2020-21.

Examining the statistics from Japan’s Ministry of Finance on direct investment flows, it seems the UK benefitted from a big inward investment from Japan into the finance and insurance sector in 2016, then there was net disinvestment in 2017-2019, and then increasing net investment in 2020-21. Conversely, there was little investment into Ireland, Luxembourg or the Netherlands in 2016, but major investments into their finance and insurance sectors in 2017, 2018 and 2020-21.